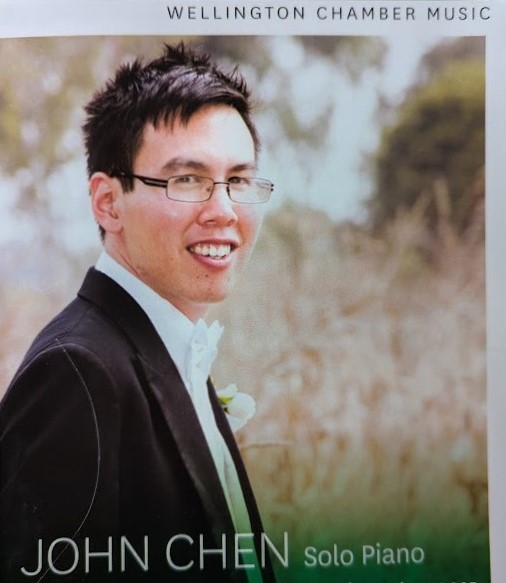

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital

(presented by Wellington Chamber Music)

FRANCIS POULENC – Three Novelettes (1928)

HENRI DUPARC (transcr. John Chen) – 4 Melodies (1869)

CÉSAR FRANCK – Prelude, Chorale et Fugue (1884)

GABRIEL FAURÉ – Theme and Variations in C-sharp Minor Op.73 (1895)

CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS – Six Etudes Op.111 (1899)

St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Wellington

Sunday, 15th June 2025

In his biographical note accompanying the programme John Chen was described as having “a passion for twentieth-century French music”, even though only one of the works in today’s recital – Francis Poulenc’s Three Novelettes of 1928 – would have qualified for inclusion in that category. On the basis of the overwhelming success of this concert one could justifiably conclude that the pianist’s sympathies had definite historical precedents in this repertoire, with playing whose style, brilliance and commitment extended backwards to works whose influence on twentieth-century French composition was undeniable.

It was, therefore, ironic in a sense that Chen’s recital today opened with music that was the programme’s sole direct twentieth century representative. Poulenc’s first of his Three Novelettes began with a beguiling sense of weightlesness, of “floating” with the music throughout the opening paragraph, in parallel with a wealth of counter-themes – a minor key episode brings a wistful touch that cheers up when firstly a toy-soldier marches by and then a clockwork dancing couple strut their stuff, before the music returns to the opening.

Chen played the next piece very much akin to the “frantic scherzo” description, with stinging attack suggesting reckless abandonment, a dimension of energy extra to how I’d previously heard the piece delivered (and blowing the cobwebs from the rafters of my idea regarding the music’s droll ambient humour in spectacular fashion!). Amends were made to my sensibilities with the last of the three pieces having a beautifully flowing, almost “grateful unfolding” kind of trajectory with its sights set upon a profound serenity.

Next came four of Henri Duparc’s 1869 Melodies, but with a difference – these were the pianist’s own transcriptions of the songs, realisations whose apparent sympathy with the ethos of the originals would surely place them in the category of a precious gift for any recitalist. The first, L’Invitation au Voyage is a setting of Charles Baudelaire’s sensuous plea to a lover to accompany him on a journey of ”abundance, calm and sensuous delight”, the music around the melody all gratuitous suggestion and scintillation. The second with its title Elégie resembles Rachmaninov’s similarly “charged” depth of feeling for keyboard texture in its rendering of words by Irish poet Thomas Moore describing the pain of a bereaved lover.

Chen’s gift for story-telling irradiates the somewhat gothic “layers” of Duparc’s setting of Francois Coppée’s La vague et la cloche (“The wave and the bell”), a dream depicting a hapless adventurer’s storm-tossed sea-voyage and a somewhat macabre bell-tolling episode in a remote bell-tower. Finally, in a rather more conventionally romantic scenario, the final Extase is a sinuously-crafted setting of a poem by Jean Lahor expressing the feelings of a lover sleeping on his beloved’s breast.

César Franck was long considered a somewhat sanctimonious and sentimental figure who composed primarily for the organ, achieving fame with his setting of the sacred song “Panis Angelicus”, which for many years hampered even his D Minor Symphony and the popular Symphonic Variations for (piano and orchestra) from being taken seriously. But the re-emergence of works like the Violin Sonata , the Piano Quintet, the String Quartet, and solo piano works such as the present Prelude , Chorale and Fugue has allowed a far more important and significant creative figure to emerge and be given his proper dues. His piano works in part represent his early career as a keyboard virtuoso with their formidable technical demands, though this work (1884) dates from his maturity as a composer and the emergence of many of those works on which his reputation now stands.

As with the later solo piano Prelude, Aria et Final, this present work features the composer’s potent amalgam of mystical solemnity, robust structural strength and a fluent melodic gift – Chen enabled both its declamatory strength and fluid animation to coexist at the Prelude’s beginning, all the while keeping to the fore that enlivening spirit, a kind of ineffable energy bent on searching for a purpose. The opening strands having explored the terrain, they then regrouped to acclaim the first strains of a chorale theme (one perhaps inspired by the bells in Wagner’s “Parsifal’) buoyed up by arpeggiated chords which moved from section to harmonic section with majestic assurance in Chen’s hands!

From this ever-increasing splendour grew a Lisztian passage that tipped the excitement over into the fugue, a descending opening figure whose explorations Chen took on a totally absorbing journey, involving different registers and inversions, building towards a sonorous climax, at which point a cadenza like passage called forth the wonderful “Bell” chorale theme and the fugue’s subject together in a stunning peroration-like coda, the notes flailing amid fanfare-like cascades before the crashing concluding chords – what more could we ask of a work and its performer but that?

There was plenty to talk about at the interval, so much so that when the pianist reappeared we all had to break up our discussions and scurry back to our seats so that the concert could “get on”! The second half began with a work that was actually new to me, and to which I had listened from a recording and failed to really enthuse about – I thought at the time the music, Gabriel Faure’s Op. 73 Theme and Variations, all a tad tired-sounding, and so was inclined to share the blame between composer and performer. To my surprise, right from John Chen’s playing of the first phrase I was made to prick up my ears as if I was hearing a different piece of music! Here the opening was strongly delivered and finely shaped, the theme not so much “solemn” in character as forthright and determined.

The variations also seemed to have acquired stronger, more characterful outlines, so that instead of waiting for each one of them to end I found myself here eager for a new one to begin! Variation One has Chen meticulously balancing the theme in the bass with gentle filigree patternings in the treble register. Next is a scherzo-like piece with contrasting energies, at first madly rushing about, then looking about to see who else might be listening, an activity which then morphed into earthier, more vigorous “jumping” figures with onlookers shaking heads in disbelief and despair! Even more exploratory were the next variation’s far-flung figurations, decorative and demonstrative, and attention-grabbing. Then came a great roulade of sounds turning like a ferris-wheel, as onlookers watched from below, craning necks as the wheel turned.

I found the sixth variation equally arresting, pinpointing both stratospheric and near-subterranean notes with great arches between them, and the seventh filling the spaces thus created with regular note suspensions run up and down like ladders. The eighth variation was a beautifully wistful and thoughtful version of the same, complete with onlookers’ “oo-er-ings”, while the ninth was even more rhapsodical and far-thinking via its creation of hitherto unglimpsed views. A restless spirit then overtook the music for the tenth variation, an insouciant up-and-down ride pushing back the boundaries of adventure to the point where the composer’s zeitgeist must have intervened at the point of such excess with the next and final variation, lifting the music suddenly beyond all striving and searching, and quietly exulting in a fulfilment of serenity. Such a different experience to my first hearing of the work, and so very rewarding…….

Camille Saint-Saens was, of course in temperament something of the joker to Faure’s philosopher. Saint-Saens was ten years older, and the relationship began as master and pupil, but it lasted sixty years, and ended as one of compositional contemporaries. They had their differences, Saint-Saens’s tastes being the more conservative, but the latter was always solicitous towards the younger man’s music, though disapproving of some of his colleague’s enthusiasms.

Their musical differences were heavily underscored by John Chen’s staggeringly brilliant presentation of Saint-Saens’s Six Etudes Op. 111, music that revelled in a number of aspects of spectacular technical display. Beginning with Tierces Majeures et Mineures (Major and Minor Thirds), the right-hand figurations’ gossamer delicacy was then eschewed by those for the left-hand in favour of a more turbulent character, after which the Traits Chromatiques (chromatic figurations) seemed to let loose a whole swarm of Rimsky-Korsakov’s eponymous Bumble Bees! Prélude et Fugue grandly acknowledged JS Bach’s pre-eminence in this form, giving a forthright theme an insistently varied accompaniment between the hands, and a fugue which followed more conventional lines while tossing in toccata-like touches such as the irresistible flourish right at the end.

The Lisztian Les Cloches de Las Palmas (which, in places, recalled for me Jack Body’s Five Piano Pieces!) is simply replete with resonances as if Saint-Saens had unlocked some kind of deeply archetypal stimulus to memory inside the listener which somehow transcends the title’s specific geographic reference. Different evocations rang out in No.5, Tierces majeures chromatiques (Chromatic major thirds) whose particular sonorities readily conjured up whole swathes of the macabre in feeling and sensation long before film composers turned such devices into cliches (Chen’s astonishing finger-dexterity here garnering jaw-dropping awe from his audience which, if anything, turned into childlike bemusement at the piece’s throwaway ending!

But all of this had to defer to the composer’s outrageously indulgent self-pillaging of a previously completed work in the concluding Toccata d’après le 5e Concerto (Toccata from the finale of the Fifth Piano Concerto)! Dedicated to one of the most eminent French pianists of the time, Raoul Pugno, the piece’s ebullient virtuosity draws from different sequences in the concerto’s finale, mingling near- exact passages with more extended and rhetorical ones while keeping the pulses and energies of the original at fever-pitch, the solo piano at the very least rivalling the soloist-and-orchestra combination in the concertante original.

Fired-up as our enthusiasms were at this point, our sensibilities were mercifully allowed to gradually reinhabit less rumbustious living-spaces by the concert’s end, with John Chen giving us the adorable slow movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Major K.330, which I knew, but couldn’t place, name-wise – the pianist came to my rescue! It closed, quite perfectly, an afternoon of uncommonly sublime music-making which will linger in my memory and in that of others – what a telling and resonant advertisement for the need many of us crave (and occasionally voice) for more piano recitals! Thank you, John Chen!