Comfy Concert No. 4, from The Chamber Pot-Pourri Ensemble

FRANZ SCHUBERT – Allegro for String Trio in B-flat Major (1816)

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH – String Quartet No.10 (1964) – dedicated to Moshe Weinberg

Elegy from “Lady Macbeth of Mtensk”

Polka from “The Golden Age” Ballet

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN – String Quartet in D Major, Op.76 No. 5 (1797/8)

Helene Pohl and Anna van der Zee (violins), Nicholas Hancox (viola), Rolf Gjelsten (‘cello)

The Long Hall, Roseneath, Wellington

Saturday, June 2nd 2025

This was the fourth concert in the series of Helene Pohl’s and Rolf Gjelsten’s inspirational “Comfy Concert” presentations at Roseneath’s eponymously-named “The Long Hall”, a venue whose “comfy” aspect per se might be regarded by some as an imagination-stretch, but whose musical rewards have been unanimously acclaimed by attendees I’ve spoken to on each of the occasions so far. Central to the undertaking have been performances by Helene’s and Rolf’s variously-constituted “Chamber Pot-Pourri Ensemble” of a number of Dmitri Shostakovich’s string quartets, as a way of commemorating the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death. However, the fare we’ve enjoyed has intriguingly involved additional concert items, all enhancing our appreciation of the Shostakovich works through fascinatingly different viewpoint perspectives.

Certainly this concert’s entertaining varieties possessed more to them than met the ear – at the time we were highly diverted by the “quantum leaping” between realms which at first seemed chalk-and-cheese, as with the plunge from the beautiful pliabilities of Schubert’s adorable String Trio Allegro into a world of ever-present unease embodied by Shostakovich’s music in general and in particular his string quartet-writing, then tangentially to Haydn’s domain of “invention, fire, good taste and new effects” circa 1798 – and with a delightful “extra” at journey’s end in the form of a 20th century return to Shostakovich at his most sardonically playful, the famous “Polka” from the ballet “The Golden Age”.

Even more diverting was the idea that the concert might have included an item from the First Smile Gamelan ensemble, whose instruments are housed at The Long Hall, and whose gong had on earlier occasions been ceremonially resounded as a kind of taslismanic beginning to these concerts – alas, indisposition of personnel put paid to such an appearance, depriving us of further colourful variance!

Still we were able to bear our loss thanks to the riches whose rewards were securely sounded – and despite the differences mooted above one could easily equate certain through-lines connecting the pieces by taking larger views of the juxtaposings – Schubert, for example, was no stranger himself to unease of a different but still existence-threatening kind, even if his music could cheerfully and stoically step outside his very real fears (as Shostakovich also did on occasions, such as here with his outrageously irreverent “Polka”). And Haydn’s ambitious treatment of form and substance in his Op.76 No.5 work resulted in the music acquiring the name Friedhofsquartett (Graveyard-Quartet) on account of the slow movement’s extended length and remote F♯ major key, characteristics that align the work with much of Shostakovich’s string quartet output.

With these thoughts in mind my memories of this concert resonate all the more – Helene Pohl began proceedings by warmly welcoming us to the Hall and drawing our attentions to the programme note concerning the music-teaching organisation Arohanui Strings, of which she herself is Patron, referring to the inspirational work done by affiiliated music tutors in many parts of the Wellington region with youthful musicians, and to the support which concerts like these can give via people’s donations to such a cause.

Then came the music, beginning with Schubert’s Allegro for String Trio (violin, viola and ‘cello), a work that broke into song immediately, while ensuring sufficient strong and definite statements around which the melodies could be adorably placed. Here the dialogue (or, “trialogue”) between the instruments was so ear-catchingly “give-and-take” it gave one an almost-naughtily enjoyed frisson of well-being, a pleasure in sound akin to relishing a portrait or landscape whose structures and hues have a kind of mutually-assured compatibility of a striking and memorable kind. With the development section we were straightaway drawn into what seemed like new page of upwardly-modulated wonderment, with the previously-voiced themes being given different aspects to explore – the playing flowed seamlessly into the recapitulation, an absorbing same-but-different journey homewards, a lovely “did we dream you or did you us?” kind of experience.

Violinist Anna van der Zee then joined the group for the Shostakovich Quartet No.10, a work introduced by Rolf Gjelsten, whose words “music that’s never truly comfortable” seemed aptly to characterise the whole of the composer’s output – certainly all that I’ve heard, anyway. He described the Tenth Quartet as something of an enigma, music by someone “who has been through darkness and tragedy”. Part of the work’s enigmas is the violently aggressive second movement, Allegretto furioso which gave rise to a quote repeated by Rolf (and whose source I’ve not been able to find) that the movement, for instance, contains “not a single human note in the music”. After this there’s an elegy in Passacaglia form consisting of eight variations, and to finish, a fourth movement Allegretto whose dance-like manner variously revisits parts of the work then returns us to the notes with which the quartet commenced.

Beginning with a kind of bugle call, part quirky dance, the first violin opened the work, the three other instruments commenting nonchalantly on the tune, which returned on the violin as the others continued their responses. These included a more resonant ‘cello melody and an eerie sul ponticello viola passage presaging the return of the bugle tune with pizzicato and gently-retiring arco support, all ambiently and pin-pointedly placed.

Any such vestige of tranquility or delicacy was then exploded in the violence of the Allegretto furioso’s attack, the violin playing an aggressive theme punctuated by stinging chords from the others. The onslaught then continued as it began, with the players often pairing for a double-edged effect – such as violins grotesquely repeating the opening together, then screaming with anguish against tremolandi from cello and viola, before taking up stinging mirror-phrases against those of the cello and viola, the latter groaning heavily against the two violins’ shrieking repeated-note patterns – and so on, until a brutal concerted repeated-note unison lambasted its way to a relentlessly hammered out ending! We sat there, gobsmacked!

The Adagio began its Passacaglia – eight variations, promising at least some visceral if not emotional relief, judging from the passionately-played opening – apart from a brief major key flirtation with a first violin phrase the mood remained sombre and dark-browed throughout, until the viola began the first few measures of the Allegretto finale – a dance which grew out of the last variation’s sustained tones and with which the second violin joined. The momentums were by turns wafted and coloured by drone-like notes, then jogged along more gratefully by various pizzicato accompaniments, the players gradually turning up the tensions as the forward moment became more restless and volatile!

We found ourselves “leaning into” the trajectories more and more with the players as the violins emphasised their running rhythms and the violist and cellist punctuated the textures with sforzandi, the music splendidly threading these elements together – gradually it all fell back until we registered to our surprise that the first violin’s reiterations of the jogtrot rhythm had become mere fragments, leaving only the music’s remnants and then silence.

The interval gave us sufficient time to readjust to the here-and-now, and for more Shostakovich! This was a precious remnant of the composer’s infamous opera “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District”, the work which had sparked a serious falling-out for Shostakovich with Josef Stalin, who found the work not at all to his taste (the Soviet newspaper Pravda published a review of the opera, allegedly written by Stalin at the time, called “Muddle instead of Music” – it was later proved to be the work of a “ghost writer”) but at the time Shostakovich found himself a near-outcast of the establishment, with all the attendant fears one associated with being “out of favour with the Great Leader”). It took, of course, the writing of the composer’s Fifth Symphony to win back the Leader’s approval!

Wellington audiences will have the opportunity to experience at first hand some more of the actual “Muddle” in question (though, alas, not the whole work!) when Orchestra Wellington performs excerpts from the Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District opera as part of the orchestra’s concert series in October of this year! For now, we had to be content with a transcription (by the composer) for String Quartet of the “Elegy” from the opera – an arrangement of the heroine Katarina’s aria from Act One, Scene Three of the opera, in which she is lamenting the boredom and oppression of an unhappy marriage.

The aria’s melody is taken up by the first violin – sad, desolate, bitter-sweet, almost lullabic in places, but with an agitated middle section. A more elegiac sequence after the music’s climax is faintly reminiscent of parts of Schoenberg’s “Verklarte Nacht” – there’s a kind of cadenza for the viola before the violin recommences the melody, the music rising through the strings before a final kind of “Amen”.

The concert’s bounteousness wasn’t yet exhausted – no less than a delectable Haydn String Quartet awaited our attention, a counterweight of sorts (or so I imagined would be the case), to the gravities exerted earlier by the Shostakovich Quartet. One of Josef Haydn’s Op.76 Quartets, it was No, 5 of the set, thus one of the last such works the composer completed. Its key is D Major and there are four movements, the first being somewhat unusually in variation form. The 6/8 opening movement began brightly and breezily, the composer beginning simply and then elaborating detail within each of the variations in ear-catching ways. The second variation, begun by the cello at the same tempi as the opening, suddenly gathered its garments and broke into a mad galloping sequence, returning at the behest of the viola who was then able to “lead off” another round at a sensible tempi, but had to put up with individual instruments “making a dash for it” every now and then! Most diverting of all was the final variation, played attacca, in which everybody simply put their ears back and went for it, up hill and down dale! Very satisfying!

The slow movement, Largo, Cantabile e mesto, was rich and strange merely in terms of its somewhat contradictory markings – “lyrical and melancholy” which reflected something of the music’s capacity to generate both contentment and sobriety or pensiveness, and accounting, of course, for its aforementioned nickname in some countries. Without recourse to any kind of tragedy or profound sadness the music demonstrated a capacity for affectiveness regarding a more-than-usual range of poignant sensibility.

Haydn then gave us a sprightly, eager, and even thrusting kind of Minuet (but not too much so, as per the marking!), one with lovely off-beat downward trajectories in places, and with a Trio that again expresses a greater emotional range of expression that one might normally expect – all beautifully realised, here with the players alive to those mood-variants and making them “tell”. The finale is one of those that “begins with an ending!” – those two opening notes would make a most exciting conclusion to any piece! in fact, come to think of it, the whole Quartet could seem in some moods as if it was composed in reverse! This was in effect the most enchanting game of chase, and was thrown off with incredible skill by the players, to the considerable enjoyment of all of us present.

And, of course, one mustn’t forget the afternoon’s “star turn” as regards pure entertainment! This was another Shostakovich arrangement for string quartet, one which even more resoundingly, I thought, proclaimed the composer’s genius as a writer for strings. Normally one hears the world-famous “Polka” from the Ballet “The Golden Age” with all its orchestral accoutrements, including a colourful range of percussion, without which the work might seem somewhat plain and lacking in essential surface impact. Here? Not a bit of it! Despite having played the original countless times as a “party piece” recording for guests (one which never fails to extract visible signs of pleasure) I got as much enjoyment and delight and titillation from the efforts of the four quartet players and the sounds they produced from their instruments as I’ve ever done – I was expecting to be entertained, but was left literally and truly beside myself with almost unspeakable pleasure!

Emma Pearson as Musetta

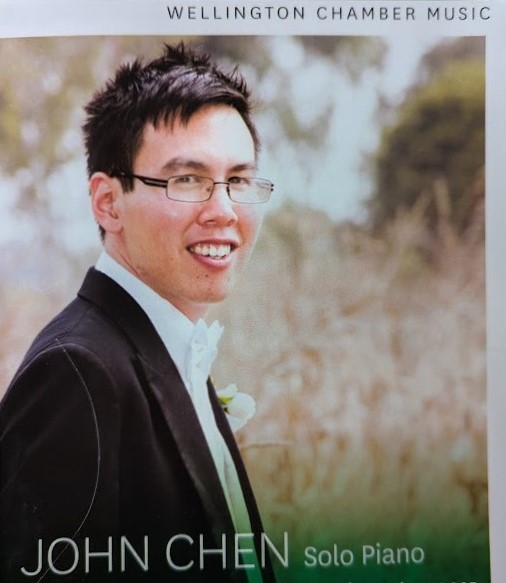

Emma Pearson as Musetta John Chen – French Piano Music Recital

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich Orchestra Wellington with Marc Taddei rehearsing Shostakovich

Orchestra Wellington with Marc Taddei rehearsing Shostakovich

Wellington Youth Orchestra – Conductor Mark Carter congratulates WYO leader Alan Kao at the conclusion of the “Fanfare and Fantasy” concert on Saturday May 3rd, 2025

Wellington Youth Orchestra – Conductor Mark Carter congratulates WYO leader Alan Kao at the conclusion of the “Fanfare and Fantasy” concert on Saturday May 3rd, 2025