JENNY McLEOD – Three Celebrations for Orchestra (1986)

ANTONIN DVORAK – The Noonday Witch B.196

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN – Triple Concerto for Violin, ‘Cello and Piano Op.56

The Ghost Trio – Monique Lapins (violin), Ken Ichinose (‘cello) Gabriella Glapska (piano)

Hamish McKeich (conductor)

Wellington City Orchestra (concertmaster, Paula Carryer)

St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Te Aro, Wellington

Sunday, 22nd June 2025

Why have I never before encountered Jenny McLeod’s cheekily iconic “Three Celebrations for Orchestra”? – particularly as the pieces are each so heartwarmingly “grounded” in atmospheres that readily recall my own childhood memories, of forests, beaches and rural celebrations that proclaim a uniqueness of experience with tradition that’s in danger of disappearing as life here becomes increasingly “global”. I thought also that it’s music that “connects” with other examples of composers’ depictions of environments and activities worldwide – the opening “Journey through Mountain Parklands” for me strongly echoed parts of Finnish composer Jan Sibelius’s “Legends”, as well as similar landscape evocations from American composer Aaron Copland – and the final ”A&P Show” was startlingly redolent in places of the latter’s ballet “Rodeo”.

As a sometimes-conductor of the Wellington contemporary music ensemble Stroma, today’s conductor Hamish McKeich was able to draw from his performing experience to recall for us Jenny McLeod’s earlier compositions as being “rather different” in style and flavour to what we were about to hear from this, a later period of her work. By then she had turned away from the avant-garde and towards more “populist” styles, declaring at one point that “both writing and performing music should definitely be enjoyable!” – a disarming attitude that has earned her compositions increasingly diverse interest and respect from audiences.

Here, we revelled in the epic, voyaging opening of the “Mountain Parklands” journey, the trajectories straightaway moving the ground beneath our feet as the textures pushed out the vistas and spectacularly opened up the scenarios – exhilarating! Those Copland-like impulses further detailed our responses, the saxophone bringing to the ambiences shimmerings of romantic allure and the piccolo chirruping its delightful birdsong, before the Sibelius-like brasses brought a renewal of the adventurous nature of our journeying, accompanied by “music blasting away on the car stereo” – (the composer’s own down-to-earth comment on the proceedings at that point!). It all made for something terribly nostalgic for me – at times I was flashbacking to those family holidays in the car again, following railway lines, traversing hills, crossing bridges and catching sight of those, my own, mountains of memory……..

Next we found ourselves “At the Bay”, the cor anglais setting a different scene, with mellow winds dancing a slow waltz with a ‘cello – such lovely wind decorations and with the horns adding beautiful colours. Strings and percussion and then horns poured out the emotion, the mood enlivening gradually and spreading though the orchestra – the brass seemed to be enjoying themselves hugely, while the percussionists kept things rolling. As the mood quietens a slow dance ensued, coloured by wood-block-like beats – everything had a relaxed “by the sea” feel, with the winds encouraging a solo cello then joining in themselves with counter-themes and decorations. it all built up to a burst of emotion from strings, brass and percussion, and then, like memory sometimes does, slipped almost mischievously back into hiding with piano-and bassoon-notes, a sliver of percussion and wind, all as elusive as a dream….

To finish, how wonderful to have an A&P Show here documented! – I loved them so much! Like one’s own pent-up youthful excitements, the music was full-on, right from the start – a big, striding theme, buoyed by strutting brass and a sinuous saxophone (the latter, incidentally, played superbly throughout by Tessa Frazer, whose name unfortunately wasn’t listed in my programme’s orchestra personnel lineup!). The winds played a kind of chirpy cakewalk, and we caught the sounds of a distant hoe-down, but here, mixing in with cameo-like episodes of different side-shows, we had a kaleidoscopic experience of images as well as sounds, everything very “outdoor” and mixing fairground excitements with more pastoral ambiences. But, like the real thing, it was all over too soon, as a percussion flourish steered us excitingly into and through that world of fantastic entertainment, everything working like a well-drilled whole – ha! – another hoedown! – taking our sensibilities for a final ride with a wind-and-orchestra gesture of all-too-familiar satisfaction and regret!

Having had our own national identities reaffirmed we were then transported to the diametrically opposite realms of Central Europe, and to a world of folkloric atmosphere marked largely by unease, superstition and brutality – Antonin Dvořák spent the last few years of his compositional life returning his attentions almost exclusively to the folklore of his native Bohemia, writing orchestral music inspired by verses from the nationalistic poet Karel Jaromir, who had published a collection called Kytice (Bouquet), one of which was Polednice (The Noon Witch). a tale which, if not exactly bloodthirsty in a visceral sense was still blood-curdling!

Though all of Dvořák’s orchestral music has a readily recognisably Bohemian character, he hadn’t before fully exploited a penchant for descriptive orchestral writing in the manner of his fellow Czech composer Bedrich Smetana with his out-and-out nationalistic work Ma Vlast (“My Country”) – it was only after Dvořák had completed his From the New World Ninth Symphony that he turned to the musical form of the “tone poem” that had been introduced by Franz Liszt and then ceaselessly pilloried by conservative critics such as the notorious Eduard Hanslick, who, up until this time had praised Dvořák’s “pure, absolute music” compositions.

In fact Polednice (“The Noon Witch”) is a masterpiece of musical description! – it’s basically, a “cautionary tale” of a mother whose child is so badly behaves she threatens him with the spectre of a witch who traditionally appears during the hour before midday to steal naughty children away. Inevitably, the Polednice DOES appear, and a battle ensues between the mother and the witch over the child, which ceases when the midday bell sounds and the witch disappears. But when the father returns home he finds his child lifeless, smothered in the arms of his unconscious wife.

The orchestral winds opened the story in deceptively charming folk-tale style, with firstly the clarinet and then the oboe depicting the naughty child and his toy cockerel. The mother’s anger burst forth from the strings, agitating in fine style, the whole orchestra then plunging into a splendidly vivid evocation of what the Polednice would do to the boy if she came to claim him! Seemingly undeterred the child sounded his toy cockerel again and the mother reiterated her anger and frustration at his naughtiness, further describing what sounded like a veritable “witch’s ride” in the orchestra.

Suddenly an ominous note on the lower brass introduced a sinister passage as the witch DID enter! – the splendid lower brass playing sounded uncannily like the dragon, Fafner, in Wagner’s “Siegfried” emerging from his cave! A kind of “fate” motif was ominously sounded by the orchestra as the witch advanced on the mother and child, the strains repeated by the clarinet and strings, and further hurled out by the brasses. We held onto ourselves or to each other as the witch came closer, orchestral momentums scarily depicting the mother’s struggles to keep hold of her child – until the noon-bell sounded and the spectral figure vanished.

In the wake of all of this, how carefree the homecoming father’s music sounded at first! And how uneasily the oboe and clarinet put the questions in his mind as to why his house seemed so silent! A brief moment of relieved recognition was followed by the unfortunate man’s rapidly escalating anxiety at finding his wife unconscious and then his ultimate horror to discover his child was dead! The orchestra’s whiplash-like concluding chords were here merciless, brooking no help or pity!

The interval provided extra entertainment for those who chose merely to stay put/or to stand and stretch their legs in front of their seats, enabling a life-enhancing view of various orchestral members and “behind-the-scenes” helpers “moving” the piano from its place up on the next platform down to a central front position for the Beethoven Concerto which was to follow – an operation performed with the utmost aplomb on the part of all concerned.

Something of the concert’s opening “holiday” mood had returned, now that the strictures of the Dvorak piece had passed, with the arrival on the platform of the soloists for Beethoven’s adorable “Triple” Concerto (violin, ‘cello and piano) one of the composer’s happiest creations! Though not ideally spacious as a performing venue (underlined by the extra space required for the three soloists!) the church’s layout ensured an extra “intimacy” of music-making, an almost “cheek-by-jowl” performer/audience situation, which gave the experience a uniquely treasurable flavour for the memory to lock away!

The first two movements gave me, quite simply, undiluted pleasure! Hamish McKeich’s direction brought forth an exciting and ear-catching range of dynamics at the beginning, getting the lower strings to “murmur” the opening phrase as if all the players were awakening the music from a dream, sounding the brief crescendo just before the top of the phrase, falling back to a whisper, and then springing the sounds forth with a start at the “rise and shine” call of the horns! All was then galvanic action, as the music snowballed into the first tutti, the energies joyous, the interplay delightful! As for the soloists, Ken Ichinose’s cello and Monique Lapins’ violin by turns sang their opening lines as irresistible invitations to “come and play”, to which pianist Gabriela Glapska responded in kind with gleeful eagerness, the three dovetailing their parts winningly in their concerted passages.

In response, the second orchestral tutti, though brief, was all whole-hearted agreement, as well as introducing a new theme, on which the soloists pounced with glee, Ichinose’s cello (as per usual in this work) leading the way, Lapins’s violin following with a winning “anything you can play I can play higher!” kind of aspect, and Glapska’s piano retorting with a “Well, I’m going to play something else – follow me if you dare!” kind of spirit! It was such a celebration of teamwork, both in the accepted “trio” sense and in the interplay of the soloists with the orchestra. I loved, too, the ebb and flow of the work’s intensities, how the lines and figurations could express something so simply and beautifully, and yet within a few seconds be pushing the musicians’ fingers into and through intensely-wrought variants of the same and emerge still in tandem at the end!

The slow movement brought lovely “covered” tones from the orchestral strings at the outset, and playing to “die for” from the soloists – firstly Ichinose’s particularly radiant lines throughout his extended opening solo, and properly concomitant responses from firstly Glapska and then Lapins, in duet with Ichinose. The movement’s a remarkably short one, and part of its time is spent “shaping up” towards the finale, which, here was taken at what could be described as a “good lick” – I even wrote down the phrase, “a “devil-may-care” tempo”, at the time! This was followed by another phrase, hastily scribbled – “Wow! – they (the soloists) are flying along in those running passages! – Very exciting!” Which was true in places, though being “The Ghost Trio” they were always in remarkable, and often enchanting accord, as with the “whose turn is it?” passages where they toss pairs of notes between each other in what seem like delightfully random “first to pick up” fashion!

The orchestra played along suitably in the exchanges as well, but at times I felt Hamish McKeich and the band would noticeably move the finale’s various tutti along, rather than pick up the soloists’ way with those delicious polacca rhythms – Ichinose, Lapins and Glapska gave the movement plenty of delicious “schwung” in their solos and ensembles (and which Beethoven actually seems to indicate for the orchestra as well by including a grace-note “kick” in their descending figure that leads to the minor-key beginning of the Polacca section). It’s a small point, but I always enjoy, as here, soloists in this work who give those trajectories in the finale something of a playful character which the orchestra can respond to in kind. But hey! – far more important was all of the acclaim, such happiness and such bubbling excitement both throughout and at the concert’s end (I sat next to two people I didn’t know at all, and soon found myself chatting enthusiastically with them about the music and the playing in between each of the items!) – it was that sort of occasion, and one that the orchestra and its members and organisers and friends should definitely consider a great and resounding success!

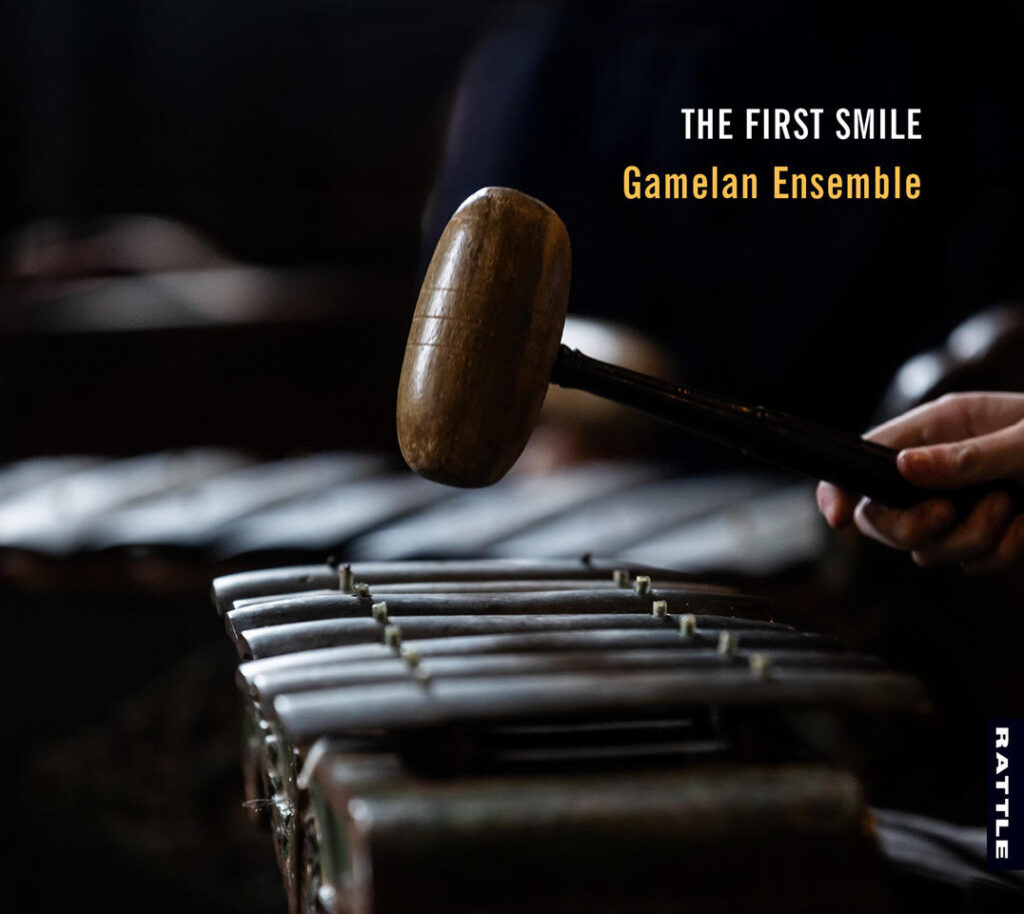

The First Smile | Gamelan Ensemble – Rattle Records (2024)

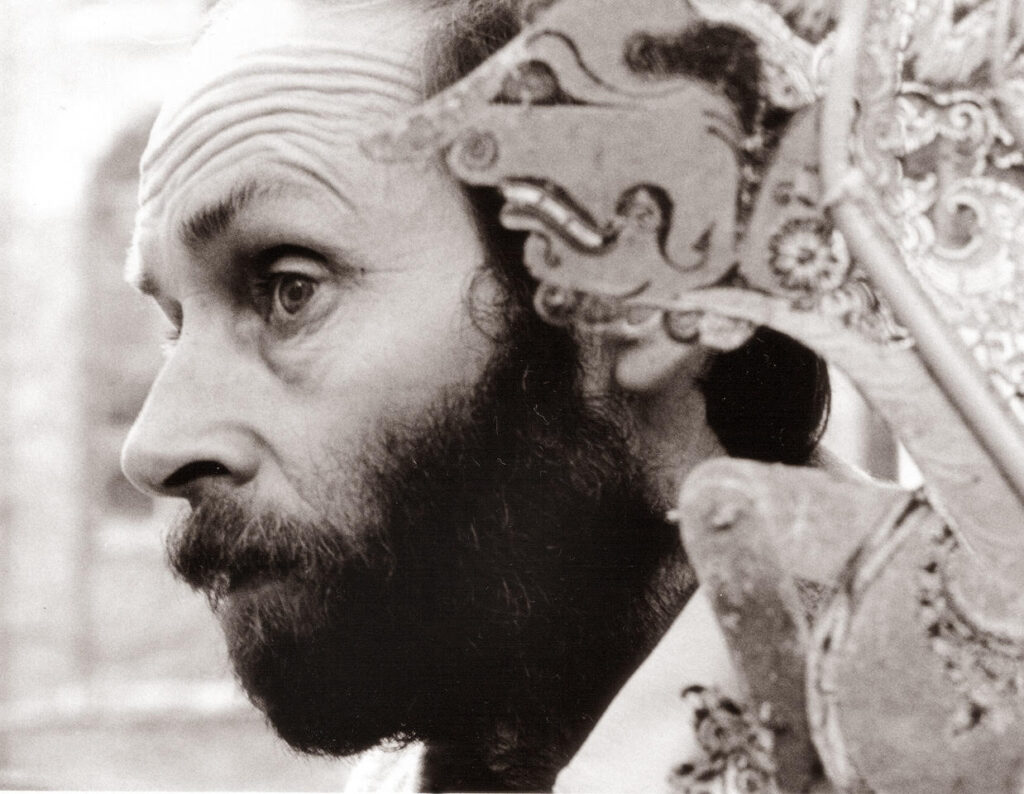

The First Smile | Gamelan Ensemble – Rattle Records (2024) Allan Thomas – photo by John Casey

Allan Thomas – photo by John Casey Gambang ( xylophone-type instrument, struck with soft beaters, and with wooden keys unlike other bronze-keyed instruments of The First Smile gamelan )

Gambang ( xylophone-type instrument, struck with soft beaters, and with wooden keys unlike other bronze-keyed instruments of The First Smile gamelan ) Saron — bronze keyed instrument struck with wooden beater ( drawing by Barbara Lyon, photo John Casey )

Saron — bronze keyed instrument struck with wooden beater ( drawing by Barbara Lyon, photo John Casey ) Gong (l) Kempul (r) : ( photo John Casey)

Gong (l) Kempul (r) : ( photo John Casey)

Donald Maurice (conductor) and Inbal Megiddo (‘cello) rehearse Shostakovich with the Wellington City Orchestra, December 2024, at St.Andrew’s Church, Wellington

Donald Maurice (conductor) and Inbal Megiddo (‘cello) rehearse Shostakovich with the Wellington City Orchestra, December 2024, at St.Andrew’s Church, Wellington

“Turtle Time” with speaker Jonathan O’Drowsky, and conductor Robert Oliver.

“Turtle Time” with speaker Jonathan O’Drowsky, and conductor Robert Oliver. Some of the performers at the conclusion of “Jack@80” at St. Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace Church, Saturday 12th October, 2024

Some of the performers at the conclusion of “Jack@80” at St. Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace Church, Saturday 12th October, 2024