“Home for the Winter”

Liam Wooding (piano) and Hannah Darroch (flute)

Music by Jasmine Lovell-Smith, Henri Dutilleux, Lachlan Skipworth, Aaron Copland and Lili Boulanger

Bedlam and Squalor – Level 1, 18 Garret St,. Te Aro, Wellington

6:00 pm, Thursday,15th May, 2025

Things were “swinging away” in great end-of-the-day style at “The Rogue and Vagabond”, the watering-place right next to central Wellington’s Glover Park, as I made my way, a little tentatively, just around the corner and further along Garret St, to where there stood, self-assuredly in its own modest way, the entrance to “Bedlam and Squalor” (ah, thought I – a first cousin to “The Rogue and Vagabond!) – but I was straightaway taken by the contrast of the sombre doorway (of the “abandon hope” sort) with the profusion, above and besides this entrance, of coloured-pencil like horizontal stripes one might have correlated to a kind of urban kindergarten or some sort of art-gallery where the Hogarth-like images I’d entertained of “Bedlam and Squalor” were in reality reverse-euphemisms for “fun and games”, and obviously nothing worse than “madness and merriment”.

Up the stairs I went, leaving those around-the-corner jollities earthbound as I ascended, finding myself in a quiet, comfortable and welcoming space not unlike a bar itself, but with tables and chairs set up in a rounded area at the room’s end, where there was a piano, beside which the two artists, Hannah Darroch and Liam Wooding, were discussing aspects of the music they were about to perform, and greeting us (myself included) as we came in. Pleasantries completed I had just settled down, finding a seat next to an acquaintance whom I’d made at previous concerts and always found most agreeable, when I discovered that, in my haste at leaving home I’d snatched up one of my notebooks, but had forgotten to bring a pen! Help was at hand in the shape and form of a bartender, who was greatly amused by the piquancy of the plight of a music critic who had come without a stylus, but who kindly brought my agony to an end by producing one – I was happy to have thus contributed a “storm-in-a-teacup” strand of incident to the proceedings now that things had been resolved!

So! – here were Hannah Darroch and Liam Wooding, formally welcoming us (we were a small but appreciative audience in that relatively intimate space) and telling us about what they were going to play for us, beginning with a piece which had give the whole recital its name, “Home for the Winter”, a piece written in 2020 for Hannah by Jasmine Lovell-Smith, and whose title was inspired by the “homeward” move made by many New Zealanders in response to the Covid 19 outbreak. The sounds seemed coaxed from out of the air, firstly for the piano, and then for the flute, the lines having a natural, organic kind of flow as if wrought by impulse, a feeling for the actions of wind and water all around – having been brought into being these elements seemed to take human form in song, which became a sort of minstrelsy, a chorus that rose up as the piano intensified the exchanges, before breaking off and leaving the opening resonances as a memory.

Having proclaimed a kind of “this is where we are” introduction, Hannah and Liam took us next to more peopled terrain, with a work by French composer Henri Dutilleux. Though it was one I’d not heard before, I knew and had already been enchanted with pieces by Poulenc, Francaix and Ropartz, and this proved, to my delight, similar kind of territory. I was almost straightaway disarmed by the opening piquancies (mysterious piano octaves echoed and gracefully “danced all about” by the flute) – and I loved the “Peter and the Wolf” opening dialogues of the second movement between the piano’s predatory wolf and the flute’s frightened but intrepid bird, and the following rhapsodic exchanges between the two, suggesting something of a singular “entente cordiale”.

A sudden escalation of energies (brilliant “molto perpetuo” playing from both musicians) seemed to clear the air of menace, entirely, and give the scenario over entirely to the pleasures of tit-for-tat exchange, our sensibilities being given plenty of air and space in places by some soaring lines before being returned to the dance! Towards the end, a cadenza-like episode from Hannah’s flute took us to a Ravel-like place not unlike Daphnis and Chloe’s enchanted grove, before the pair rejoined forces for an ever-accelerating coda, exhilarating for us all in its shared energies and pleasures.

Next was a recently-composed (2022) sonata by Australian Lachlan Skipworth, introduced by Liam, and described by him as “very refreshing” to play, though adding the proviso that the time signatures in the score with their frequent changes – 20/16, 10/16, 18/16 – certainly posed something a “challenge”. From the beginning I found the work a same-but-different experience to that of the Dutilleux, here an almost Gaelic world of exhilaration, with the opening “chaos of delight” morphing into a folk-dance blend of carefree abandon and strongly-pulsed movement.

The piano breaks off to play a solemn, repeated note-pattern to which the flute adds a lovely, rustic song-like sequence, borne along by its own airiness and spaciousness, hymn-like when the piano intensifies the mood, and seemingly tossed into the play of winds and waves when both instruments dance along the hilltops of the melody’s liberated lines – entrancing! Just as spell-binding is the dialogue of voices sequence which follows, like a pair of birds enacting a defining of territories, or a courtship ritual, one which leads back to the exuberance of the folkdance – if the conclusion isn’t quite of the grand finality one might expect, one might say it has an attractively insouciant “well, there it is!” manner at the end.

Our “food for thought” interval was sufficient to process what we’d heard (delightful!) and clear our decks for the next offering, a “different again” experience promised, which Hannah described for us as “Americana in music” – this was Aaron Copland’s Duo for Flute and Piano, again something I hadn’t heard (oh, the ignorance of some music critics!), and naturally looked forward to an introduction to the piece. The opening movement, marked as “Freely” by the composer, takes us straight into the world of the latter’s ballet “Appalachian Spring” with the flute playing solo, a “voice in the wilderness”, spacious and nostalgic, with the piano’s entry contributing to the characteristic, almost unmistakably “open” sound. The flute begins the dance, strands of movement varying its trajectories, with the piano amusingly “oom-pah” at one point just before the big flute solo! Another pronounced “echo” for me is the similar ambience to the Third Symphony towards the end, a kind of salute to an idealised past…..but, then, what a quirky kind of conclusion! – those sharply-abrupt chordings are almost amusing in their air of dismissiveness!

“Poetic, somewhat mournful”, says the composer at the head of Mvt.II – piano and flute seem to be either looking for or avoiding one another at the start – most of those open harmonies have closed up, and whatever congress the instruments strike, each seems somewhat nonplussed by the other – there’s a moment of accord in a more animated and heartfelt middle section, but compared to the opening, it’s a bit like the difference between a dream and an awakening (whichever suits which!).The piano returns to its lonely furrow, and the flute raises its head for a heartfelt and sonorous single-note look-around!

Both espy a notice saying “Lively, with bounce!” – so the piano “bounces” and the flute catches on! And what better than a square dance? – lovely, palms-skyward trajectories, with quirky harmonic comings and goings, with the flute occasionally intoning “Where are you?” as the piano rumbles up and down the stairs! – “Back to the dance!” they both chorus, nostalgically smoothing-over the rhythms here and there, but as quickly resuming their “hide-and-seek” – suddenly Hannah’s flute espies an open window and with Liam’s piano in hot pursuit catapaults right through it! – freedom!

Has this been music I’m writing about or some sort of “anything you can do I can do better” kind of game? It just seems that way, at times – but whatever the case, we in the audience were tickled to pieces by it all – and just to show that life bears SOME resemblance to art, we were invited by our stalwart artists to return to our lives with a kind of encore, a piece by Lili Boulanger appropriately entitled “Nocturne”, the flute singing a lullabic song over piano octaves, the tones soaring and settling over gorgeous keyboard undulations, while the harmonies coalesce slowly and beautifully.

Hannah and Liam, you and your instruments brought about such delight and contentment for all of us present this evening – any thoughts of bedlam and squalor were forgotten as I took my leave of my companion (deftly remembering on the way out to return the borrowed pen!) and descended those stairs and met with the open air once again, trying to recall what day it was, where I was, where I was going and what the music was that was playing in my head as I walked through streets that bore no relation, it seemed, to any of those sounds….and I thought it was definitely all part of something well worth remembering……

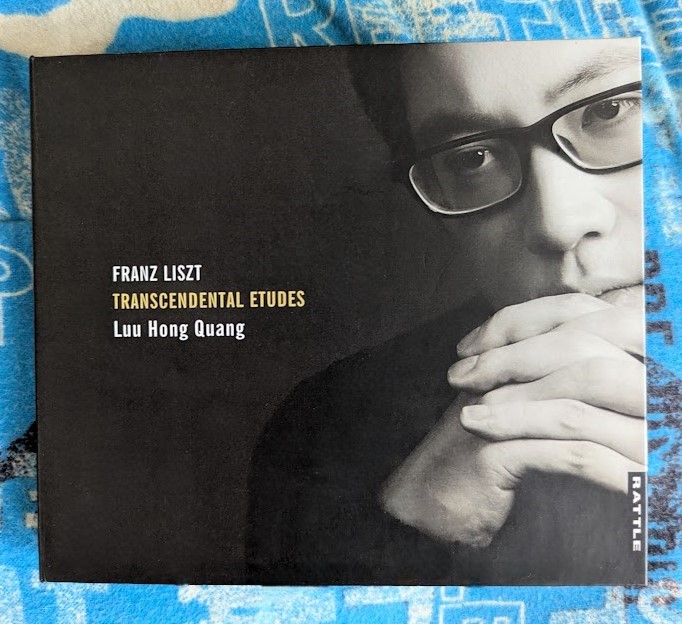

Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu

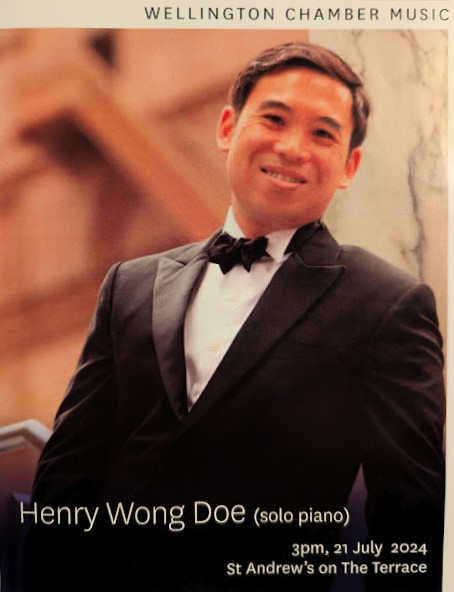

Wellington Chamber Music presents :

Wellington Chamber Music presents : Orchestra Wellington Music Director, Marc Taddei – photo credit: Latitude Creative

Orchestra Wellington Music Director, Marc Taddei – photo credit: Latitude Creative Somi Kim, piano, plays Germaine Tailleferre’s 1924 Piano Concerto with Orchestra Wellington – photo credit: Latitude Creative

Somi Kim, piano, plays Germaine Tailleferre’s 1924 Piano Concerto with Orchestra Wellington – photo credit: Latitude Creative Soloists Emma Pearson (soprano), Margaret Medlyn, (mezzo-soprano), Emmanuel Fonoti-Fuimaono (tenor) and Robert Tucker (baritone), with the Orpheus Choir of Wellington, Orchestra Wellington, and Music Director Marc Taddei – Photo credit: Latitude Creative

Soloists Emma Pearson (soprano), Margaret Medlyn, (mezzo-soprano), Emmanuel Fonoti-Fuimaono (tenor) and Robert Tucker (baritone), with the Orpheus Choir of Wellington, Orchestra Wellington, and Music Director Marc Taddei – Photo credit: Latitude Creative