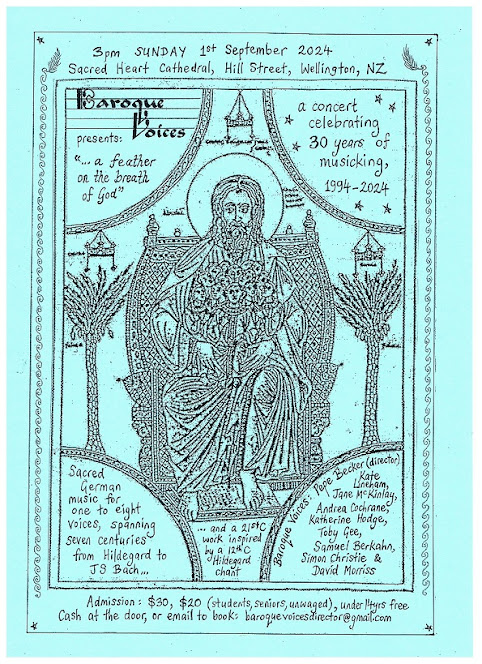

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach –

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach –

Sacred German Music for one to eight voices spanning seven centuries

Music by Hildegarde of Bingen, “The Tannhauser”, Wizlau von Rügen, Caspar Othmayer, Johannes Walther, Johannes Eccard, Heinrich Schütz, Johann Michael Bach, Johann Ludwig Bach, Johann Sebastien Bach, Pepe Becker

Baroque Voices: Pepe Becker (director), Kate Lineham, Jane McKinlay, Andrea Cochrane, Katherine Hodge, Toby Gee, Samuel Berkahn, Simon Christie, David Morriss

Additional BV singers: Jo Hodgson, Milla Dickens, Nigel Collins, Herbert Zielinski, Roger Wilson – Nota Bene Choir: Katie Chalmers, Tina Carter, Vicki Mabin, Lindsay Groves – The Bach Choir: Jonathan Lane

Sacred Heart Cathedral, Hill St., Wellington

Sunday, 1st September 2024

One had only to close one’s eyes at the beginning and one was back in an imagined, but definitely different time – the Middle Ages. Such was the power of evocation generated by singer Pepe Becker with her voice, the musical instrument she was playing while singing, and the actual words and music created nine hundred years before by the renowned composer Hildegarde of Bingen (1098-1179). The sound itself, too, had a transcendental, other-worldly quality, the interior of the newly refurbished Catholic Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Hill St providing a properly spacious ecclesiastical setting which “gave back” a feeling of a distant source being tapped and revitalised both regarding the performer and all who were present at those unique sounds’ inception.

This conjuration began a presentation by Wellington’s Baroque Voices directed by soprano Pepe Becker, which featured aspects of the previous thirty years’ activity by the group, and included a reappearance (where possible) of past members of the group to present a final item. The range of repertoire included pieces featuring from one to eight voices, and spanning seven centuries, reflecting a number of styles associated with different eras of composition.

A glance at the programme’s history of Baroque Voices’ activities detailed the range and scope of the group’s repertoire in some depth, bringing to mind a number of highlights people would readily remember by dint of the bold adventurousness, committed zeal and remarkable excellence, both technical and musical, of these undertakings. Everybody will have favourite memories of certain occasions, mine being of the Monteverdi projects, the delightful explorations of the Books of Madrigals over the years and the absolutely stunning 2010 (can it be so long ago?) performance of the Monteverdi Vespers of 1610 at St. Mary of the Angels Church whose sound’s burnished splendour still stays in my memory!

Whether one chose to close one’s eyes and experience the intrinsic exquisiteness of the sounds alone, or gaze about the visual splendours of the building to augment the music’s “time-and-place” experience it was a feast from the very first aforementioned moment of presentation, in this case Pepe Becker’s performance of Hildegarde’s O Euchari, complete with the singer’s own shruti box drone accompaniment, not, as one might at first think, a musical glorification of the Eucharist, the celebration of bread and wine becoming the body and blood of Jesus Christ during the Mass, but a tribute to a 3rd-Century missionary Eucharius who became the bishop of the city of Trier. The second of two single-voice pieces was a Spruchdichtung (song/poem) sonorously sung by bass Simon Christie, a moralistic piece emphasising freedom from sin and guilt with God’s help and grace. The contrast between the two solo items nicely encapsulated the intrinsic variety of mood, moralistic tone and spirituality throughout the remainder of the concert, as the presentation moved through a sequence which gradually increased the number of voices, and with one or two exceptions during the first half preserved a chronological composer order.

This had the effect of frequently enticing one’s ear with variation – it was, in fact, a beautifully worked-out programme in all respects, with even the instances of leap-frogging chronologies giving pleasure rather than confusion, as with the later Caspar Othmayer (1515-1553), his 2-part songs rightly taking their place with the other 2-part pieces, ahead of three- and four-part polyphonic hymns of Nikolaus Apel (1475-1537).

Inevitably there were pieces which especially charmed my ear, even though another person’s reaction could well single out different things for different reasons. For instance I particularly relished the somewhat “didactic” atmosphere created by the interval between the two voices (Pepe Becker and Jane McKinlay) in Wizlaw von Rügen’s “Ich warne dich” (I warn you), and also the following “Kyrie magne Deus potentie” (Lord, great God of power) from the two “vocal heavyweights” (Simon Christie and David Morriss). And a little later I found myself particularly drawn to, firstly a two-sectioned hymn (“A solis ortus”) whose first unison part featured five voices, and then a polyphonic reworking of the theme by Nikolaus Apel for three voices (Pepe Becker, Samuel Berkahn and David Morriss) the words beautifully describing something of the visible physical boundaries of creation, with Christ as ruler of all.

The leadup to the interval had something of an irresistible “rolling” quality as well, beginning with the beautiful four-voiced hymn “Nova veniens” describing the city of Jerusalem, from a melody collected by Nikolaus Apel in 1494, and the buoyantly irresistible five-voiced motet by Johannes Walther beseeching the protection of the Holy Ghost “Nu bitten wir”, which I found so invigorating! While it might have seemed strange to then flip-flop back to Hildegarde, Pepe Becker obviously wanted something a bit out of the ordinary for a “first-half closer”, which she was able to organise by pairing the famous Hildegarde solo-voiced “O ignis spiritus” (the sound-world similar to that for “O Euchari” which opened the concert) with a new composition-cum-arrangement by her drawing from the “spiritual fire” of the solo-voiced sequence, and “re-orchestrating” the piece for eight voices and hand-held rock percussion effects – all of which worked sensationally well! (Pepe’s idea was that the theme of “life, light and wonderment” of the original text could be augmented by extra voices and percussion to push the “blissful pleasure” of the text into more extreme realms “verging on pain”) – it all indubitably typefied the questing spirit of its instigator to what seemed to this listener as remarkably appropriate effect!

Baroque Voices 2024

Baroque Voices 2024

Left to right: Jane McKinlay, Andrea Cochrane, Katherine Hodge, Pepe Becker (director), Toby Gee, Simon Christie, Kate Lineham, Samuel Berkahn, David Morriss

Interval gave us a time of shared discussion and delight before we were returned to what was for the presentation venturing into a new era, the Baroque, beginning with the beautiful motet by Johannes Eccard “Christ ist erstanden” (Christ is risen) for five voices (including soprano Kate Lineham and alto Andrea Cochrane, whose work for Baroque Voices I’ve not mentioned until now, and whose contributions helped to enhance the work’s delight.) The two Schütz motets which followed gave us by turns beauty (“So fahr ich hin”) and strength (the more declamatory “Herr, auf dich treue ich”), though I was particularly “taken” by the six-voice work of the next composer, Johann Michael Bach (whom I’d never really heard of beforehand!), and whose more vigorously homophonic style produced an engaging and decorative “bubbly” effect in places in his motet “Sei Lieber Tag willkommen!”

Two more motets by Heinrich Schütz, both for seven voices, brought more singers into play, alto Katherine Hodge in both and counter-tenor Toby Gee in the second of the two (both had of course previously contributed at various stage of the concert) – in the case of the first motet with the well-known text “Ich Weiss, das mein Erlöser lebt” (I know that my Redeemer liveth), and an Advent text for the second, “Der Engel sprach zu den Hirten”, the first an urgently expressive statement of belief familiar, of course, to Messiah-buffs, using the contrasts between lower and higher voices to both lyrical and dynamic effect. No less celebratory was the second, with (again precursing “Messiah”) all those resonant descriptions of the newborn baby Jesus announced to the shepherds in the fields resoundingly bringing forth “Alleluiahs” at the piece’s end.

Appropriately, the great Johann Sebastien Bach’s music was part of the “closing ceremony” at the concert, being the last item but one, and certainly the most challenging to bring off – this was the eight-voiced double-choir motet “Komm Jesu, komm”, requiring all of the virtues on display throughout the afternoon rolled into one! I found the music intense and “exposed”, the one-to-a part giving each voice nowhere to hide, and making the journey by turns enchanting and tremulous, exhilarating and daunting, and playful and harrowing, all of which characteristics came and went in this incredible performance – there were beautiful, heart-warming and stirring moments, with just the occasional sense of strain, all defining the journey in both individual and collegial ways. The sense of pilgrimage was palpable, and the feeling of arrival at the journey’s conclusion treasurable. Bach had obviously conceived and crafted it as an experience for performers and listeners alike, and here, the achievement of those ends was tangible and well wrought.

Having completed its “Odyssey” the group deemed it time for a celebration, with past BV members still within coo-ee, and ready and able to revisit what director Pepe Becker described in the programme as “the memories of joyous times singing together”. Tributes were also paid to singing colleagues who have since died, and to whom the presentation’s final item, a motet by JS Bach’s uncle, Johann Ludwig Bach’s “Das ist meine Freude” was specifically dedicated. Both the declamatory opening and the swirling, melismatic responses were tossed backwards and forwards with terrific elan, before a “duelling banjos” contrapuntal exchange and a final declamation concluded the joyous work.

Little more need be added to the above, save for expressions of pleasure and gratitude towards Pepe Becker and Baroque Voices for this “coming together” of history with the present in such a richly-wrought and life-enhancing manner for us all to enjoy.