Wellington Chamber Music presents :

Wellington Chamber Music presents :

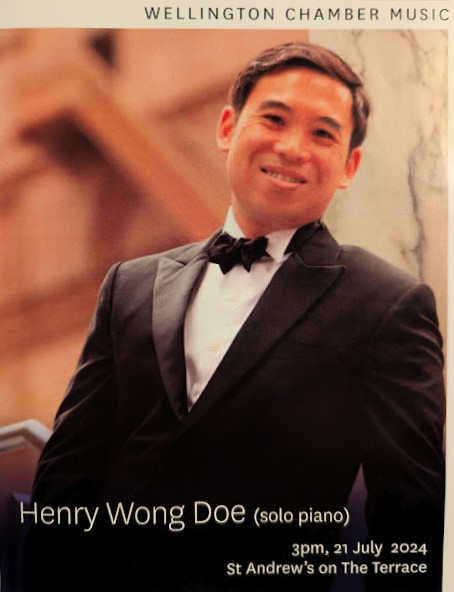

HENRY WONG DOE – Piano Recital

FRANZ JOSEF HAYDN – Sonata in E Minor Hob.XVI:34 (1784)

LEONIE HOLMES – Time Rustling for piano and fixed media electronics (2023)

ALBERTO GINASTERA – Piano Sonata No. 1 Op.22 (1952)

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN – Nocturne in D flat Major Op.27 No.2 (1836)

MODEST MUSORGSKY – Pictures at an Exhibition (1874)

Sunday 21st July 2024

St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Welliongton

Consider, reader, if you will, the piano recital – a presentation involving a single musician playing on an instrument which has inspired some of the greatest, most profound and far-reaching musical compositions ever devised by human beings within the framework of Western civilisation.

The classical repertoire alone for pianists seems boundless, including sounds associated with early keyboards and gradually evolving over centuries to the majestic tones wrought by today’s concert grands – instruments capable of reproducing near-orchestral swathes of tones and timbres which give multifarious tongue to all kinds of compositions, both original and transcribed from any era or alternative sound-source. And the music written for a single player and instrument alone is itself so richly-extensive as to commandeer a lifetime’s attention and satisfaction.

Which leads me to pose the question – WHY is it that the piano recital itself has seemed of recent times to have lost some of its former frequency, or currency, or status, or allure, or more to the point, NECESSITY in the music programmes of various organisations?

Time was in Wellington, for example, when every international piano soloist (or guest instrumentalist or singer) who appeared with the NZSO gave a solo recital as well. Quite apart from the stellar line-up which I “missed out” on seeing over the years (including luminaries like Claudio Arrau, Annie Fisher, John Ogdon and Tamas Vasary), I WAS fortunate enough to hear in the 1970s and 80s artists such as Alfred Brendel (an all-Beethoven programme), Vladimir Ashkenazy (Mozart and Chopin), Alicia de Larrocha (an extraordinary all-Spanish recital), Peter Frankl (Chopin), Jorge Bolet (Schumann, Grieg and Liszt) and Stephen Hough (Schubert), in recital in the Town Hall playing music that seemed their “meat-and-drink” when compared with the fast-food popularity of the “standard” piano concerto repertoire they also performed with the orchestra.

Now I love piano concertos – don’t get me wrong, here! – who wouldn’t want to hear those works by Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Saint-Saens, and Ravel, played by a world-class pianist? – It’s just that piano concertos represent a one-sided aspect of pianism when set against the solo repertoire that’s just as much their and our heritage. And it’s a heritage we concertgoers in t his part of the world are being deprived of.

Such a loss was underlined in spectacular fashion last weekend at a Wellington Chamber Music Concert which featured a magnificently-played solo recital by Auckland-born pianist Henry Wong Doe, who’s back home in New Zealand to visit family and take some time out from his current duties as Professor of Piano at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. I had not long ago reviewed Wong Doe’s most recent recording for Rattle Records of one of today’s recital’s “jewels”, Musorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” – https://middle-c.org/2018/02/two-resounding-recordings-from-rattle-classics-and-a-feisty-newcomer/ – so I was interested to have the chance to compare my impressions of the two readings.

While the CD enterprisingly linked the Musorgsky with another work inspired by pieces of art, New Zealand composer Eve de Castro Robinson’s, fantastically-wrought “A zigzagged gaze”, Wong Doe included at today’s St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace recital, a work by Aucklander Leonie Holmes, Time Rustling, for piano and fixed media electronics. This had been one of six works commissioned by the pianist from different Kiwi composers living both in New Zealand and in places around the world in 2022, Wong Doe inviting them to write pieces illustrating their experiences and perspectives during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Otherwise the programme was a kind of compendium of the recitalist’s art, with works from the classical, romantic and twentieth-century eras, one which could be simplistically described as a “something for everybody” presentation, but whose essence expressed much more than any such glib kind of prospectus – each piece had its own “attitude” and special character in its own right.

Take the Haydn E Minor Sonata Hob.XVI:34 which opened the recital, for instance – the first movement so intriguingly equivocal at the beginning, the pianist’s upward arpeggios quizzical and questioning, and with “full stops” at the ends of some of the sequences – what might Haydn have been thinking? – Wong Doe generates moments of volatility to the discourse, contrasting dynamic levels and places where the horse seems to be momentarily given its head before being reined in, sounding in places not unlike a young Beethoven, but ultimately with more circumspection than certainty, especially at the movement’s end.

The slow movement sounded vocal-like from the outset, the line florid and decorative. The middle section explored both minor and major key changes before returning to the opening, Wong Doe’s agile fingers making the lines seem like embellishments of themselves, steering the music towards the final movement’s darker territories without a break. He then spurted into the finale’s Vivace molto with a will, presenting incredibly quicksilvery fingerwork, relying on velocity and brilliance for effect and playing down the opportunities for variety of touch and droll humour that a slightly more varied tempo would have given – still, the effect was undeniably exhilarating!

After this came the Leonie Holmes work, part of the pianist’s “Perspectives 2022” project referred to above, and which Wong Doe recorded for Rattle Records on RAT D147 2023 (see this review’s heading). This was one of two pieces from the set whose composers used electronic sounds in their work (Leila Adu-Gilmore’s work “Home” was the other), the remainder being entirely for acoustic solo piano and player.

I’ve always liked the unvarnished honesty of Leonie Holmes’s work, the most recent one I’ve heard being an orchestral piece “I watched a shadow” premiered by the NZSO on consecutive nights (May 17/18th) in Auckland and Wellington. I thought Holmes’s work on that occasion easily out-grew its inspiration, a friend’s somewhat homespun poem, the resulting orchestral rhapsody convincingly conveying an austere soundscape undergoing what seemed as much oceanic as tectonic forces at work, enlivened by ebb-and-flow wind-and-brass irruptions.

Here, by comparison, the stimulus originated more from within, a meditation upon time characterised strongly by the isolation of the Covid-19 era. Holmes wanted to “grow the piece” via the “strange ways” of time by refracting her initial sketches of memories of the sounds of wind rustling through the branches of trees through an electronic media, then mixing the later piano timbres with these earlier memories.

Beginning with electronics whose sounds resembled a chord which burgeoned and refracted, the piano responded with gently-voiced melancholic tones., the combination sometimes augmenting or taking turns with one another – a tolling-bell sequence mirrored, then drifted apart, while the tape’s rumbling, sighing ambiences prompted low, murmuring chordal utterances from the piano, Bartokian chords growing into scherzando-like animations. As the intensities faded, gentler Debussian piano sounds took over– gentle pin-pricks of sound-light gradually bade those beautifully ambient chords a farewell.

Next we heard a starkly contrasting piece, Alberto Ginastera’s First Piano Sonata, a tribute by the composer to the folk rhythms of his native country, Argentina, and producing a coruscating display of keyboard physicality from the pianist. As well as their South American flavour, the themes had a Prokofiev-like energy and piquancy with the music’s more lyrical moments of the music framed in toccata-like trajectories which kept the listener’s blood pulsating right up to the coruscating repeated-note onslaughts of the movement’s final flourishes.

This was followed by a presto misterioso second movement, setting sinister “whirling dervish” textures against breathlessly-repeated toccata-like sequences. Wong Doe’s feathery brilliance conjured up something of a nightmarish soundscape traversal which disappeared at the end as eerily and wraith-like as it had begun. What a contrast with the slow movement’s building from the silences a series of quietly expressive “figures” their immobility imbued with portentous mute intention, before opening up and giving tongue in agitated tones. After a climax the sounds seemed to withdraw into themselves once again as mysteriously as before.

Suddenly the finale’s “ruvido ed ostinato” erupted, joyously and frenetically under Wong Doe’s fingers, the dance-like rhythms whirling all of us along on a growing tide of energy and exuberance, animating those infectious-sounding folk-melodies beloved of the composer – the whole movement represented an irresistible bubbling-up of exhilaration towards a final, volcanic surge of energy from the pianist up and down the keyboard. It was Incredible stuff, bringing some people to their feet, and leaving others like myself too gobsmacked to do little more that applaud as if in a daze!

After some of us had “talked among ourselves” over the interval and calmed down, we were ready for the second half, beginning with a Chopin Nocturne, and concluding with Musorgsky’s famous “Pictures”. The Chopin work, in D-flat major Op.27 No. 2, was one of a “pair”, which the composer was fond of crafting with these works. This one, in contrast with the more turbulent No. 1, was more consistently song-like throughout, a mini-crescendo of excitement apart in the middle section of the work (very operatic-like, and betraying the composer’s fondness for the voice.)

Wong Doe charmed us with this, beautifully demonstrating to us the well-known description of “Chopin rubato” – the leaves of the tree are being blown every which way by the wind, but the trunks remain solid and keep strictly in time.

I hadn’t heard Wong Doe’s recording of the Musorgsky for a while, and thought I’d prefer to encounter it afresh, in any case – at the start I thought the gestures suitably invigorating and virile, presenting a composer who, rather than bowed by grief at the loss of his artist friend, Victor Hartmann, seemed determined to do his memory justice via the inspiration given to him by the artist’s pictures.

While making the most of the contrast the cycle afforded, Wong Doe didn’t go into “Horowitz territory” in terms of over-orchestrating the different subjects – The Gnome, for instance he played hard-and-fast, carrying over some of the opening promenade energies without a pause or break, and emphasising the creature’s malevolence. The Old Castle evoked the Troubadour, but not so much his song as his playing, as also with the caprice and playfulness of the children in Tuileries. But Bydlo (The Ox Cart) was here superb, massive and relentless at the climax, and with its decrescendo given all kinds of variants of tone and colour. The Ballet Of Unhatched Chicks then properly enchanted, while the two Jews, Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle were brilliantly operatic in their interactions.

I enjoyed the delightful garrulity of the Marketplace at Limoges, here contrasted stunningly with the eerie Catacombs – suddenly we could scarcely dare to breathe in between those massive chords and their silences! I also remember the almost Lisztian transcendence of the Cum Linguis in Lingua Mortua (Musorgsky’s own schoolboy Latin!) and the lump-in-throat effect Wong Doe’s playing had, both here and in his recording.

Baba Yaga was simply breathtakingly done with almost blindingly brilliant finger-work, with the central part’s eeriness and menace strongly drawn! Some pianists hold back with the introduction of the Great Gate of Kiev theme, as if hearing it from a distance the first time (which I quite like), but Wong Doe gave it his all straight away! Both the succeeding priest’s hymn and the massive bell strokes were begun softly, but the re-entry of the Promenade theme caught us up in its growing excitement until it all seemed nothing but great festive bell sounds, a ceremony as all-embracingly spacious and reverberant as one could want at the end.

I wish I’d taken more notice of the Gareth Farr encore, whose name I don’t even remember, such were the resonances still playing in my head from the Musorgsky! I remember soft, tolling bell sounds, with rhythms beginning to bubble and shimmer, while underpinned by deeper, richer sounds, until the shimmering textures reached a bubbling-over point, after which everything gradually receded, and calm was restored again. Someone who had kept his or her head better at this point might well be able to add to this somewhat distracted account of mine with more information – I was still wandering in my head, lost somewhere in Kiev, in thrall to those sounds that had made the afternoon’s piano recital such an enthralling experience……