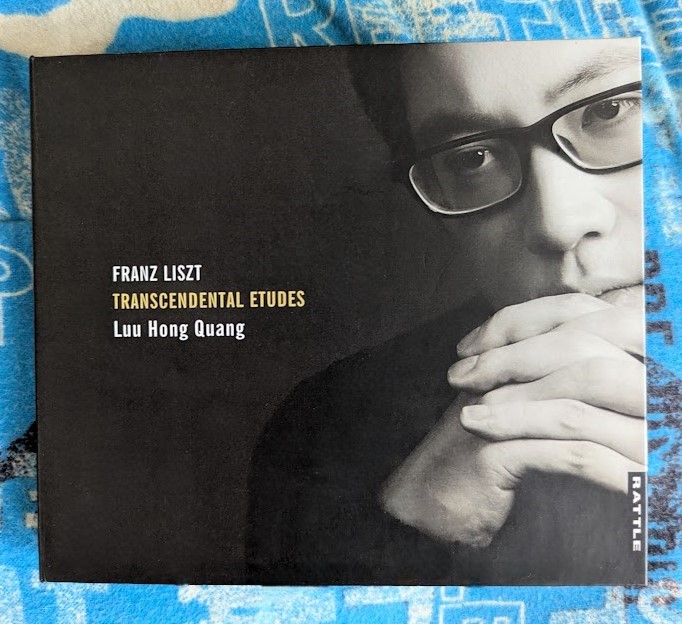

FRANZ LISZT – Etudes d’execution transcendante S.139 (Transcendental Etudes)

Luu Hong Quang (piano)

Rattle Records RAT-D152 2024

Reviewed “Middle C” November 2024

Vietnamese pianist Luu Hong Quang is currently (2024) in Wellington while studying for his Doctorate of Music with Professor Jian Liu at Victoria University’s School of Music. It’s a far-flung location from which to throw down the gauntlet to the wider world of pianism at large – but Quang has done this with a new release from Rattle Records which presents one of the piano repertoire’s most formidably challenging works, Franz Liszt’s “Etudes d’execution transcendante”. The recording was actually one that Quang made, appropriately enough, in the concert hall built next to Liszt’s actual birthplace in Raiding, Austria (formerly known as Doborján when part of Hungary at the time of the composer’s birth). No precise recording dates are given, though the pianist recounts in a booklet note a sense of the pilgrimage undertaken over a period of eighteen months to learn and master the work, which culminated in his first public performance in December 2022 at the Vietnam National Academy of Music in Hanoi. (I have since contacted Luu Hong Quang and learned that the recording took place in July, 2023.)

The genesis of Liszt’s Etudes is well-known, having their origins in twelve studies (Étude en douze exercices) he first wrote in 1826 when barely sixteen, then majorly elaborating on them in 1837 (Douze Grandes Études), after having fallen under the performing spell of Paganini and determined to emulate on the piano what the already legendary fiddler was achieving on the violin. By the 1850s, and having long given up the life of the virtuoso, Liszt then resolved to bring some of his youthful technical excesses to heel and “simplify” the studies (only one, “Mazeppa”, is considered even more difficult in its 1852 revision), emphasising the pieces’ poetry and grandeur and generally “playing down” their overtly prestidigitatorial qualities. And while the lighter Erard pianos of the 1830s made those earlier versions less awkward to manage, the heavier “action” of the newer pianos from Russia and Vienna which were gaining in popularity made passages from the 1837 Etudes impossible for all but the fingers of a Liszt!

Even so, for years these works were regarded as the preserve of “super-virtuosi”, having to wait until February 1903 to received their first documented premiere performance as a complete set from the legendary Ferruccio Busoni at the Berlin Beethoven-Saal. Traversals of the entire set remained rare both in concert and on record in the intervening years up to the 1960s – notables such as Egon Petri (1927), Jose Iturbi (1930), Jean Doyen (1943) and Earl Wild (1957) gave concert performances – but the first complete recording wasn’t set down until 1956, when Russian/American pianist Alexander Borovsky recorded the work for Vox, followed then by Gyorgy Cziffra in 1958 and Lazar Berman in 1959. Incidentally (and surprisingly), I can find only a single concert performance of the cycle thus far documented in New Zealand, that by visiting American pianist Kyrill Gerstein performed in Auckland in 2015.

Flash forward to 2024 and it seems as if a “virtuoso revolution” has taken place in world pianism since the Millenium, with almost fifty versions of the Transcendental Etudes I counted as currently available on recordings listed on the prestigious “Presto Classical” website. And now adding to that number will be Luu Hong Quang’s brilliantly-played disc, produced and sonorously recorded and mixed by Paul Carasco, and elegantly presented by Steve Garden’s Rattle Records in association with the support of Professor Jack Richards.

I decided I wouldn’t here set Quang’s recording against any other of today’s “super-virtuosi” for direct comparison, but rather allow my responses to resonate within my own sound-world of accumulated memory and feeling from experiences of first getting to know these works well. This took place through what have since become classic recordings of the complete 1852 set made by Louis Kentner, Lazar Berman and Claudio Arrau (I also heard a recital disc of Vladimir Ashkenazy’s at this time, though, sadly, only of excerpts). These were the performances which I’d first encountered and which had, from my first hearing of “Harmonies du soir” on that single Ashkenazy disc, drawn me irretrievably into the sound-world of what I came to regard as one of the composer’s most astounding creative achievements. In the light of those three stellar, though vastly different performances quoted above, Quang’s performances are as much redolent of my youthful impressions of this music as they seem freshly-minted to my ears – on a superficial level they most resemble Louis Kentner’s in that they seem primarily concerned with each piece’s “inner being” rather than its external display of whatever. Which is not to say that Lazar Berman, Claudio Arrau or Vladimir Ashkenazy all put virtuoso display ahead of poetic feeling in their readings, but rather that Quang, like Kentner, seemed to unselfconsciously intertwine the music’s “wow” element inextricably with its poetry, so as to constantly draw attention to the view rather than merely to an interpreter’s presentation of it.

Thus the opening “Preludio”, intended to arrest the listener’s attention right from the outset, does so with a true Lisztian combination of brilliance, quixotic wit and suggestive harmonic sleight-of-hand, Quang announcing the composer’s and his music’s credentials in an action-packed nutshell. Though most of the studies have descriptive titles, we’re then plunged straight into one of the two for whom Liszt named merely by their key, in this case A Minor, whose opening rhythmically resembles Beethoven’s famous C Minor Symphony’s opening, but whose restless, quixotic character suggests a more compulsively whimsical spirit – Quang’s playing brings to mind his own reference in the notes to Paganini himself.

Things settle down with the beautiful “Paysage”, a landscape conceived here, it seems from “out of the air’, such is the spontaneity of phrasing and colour that Quang conjures from the notes, with the wonderfully dramatic midway modulation taking us into a differently-hued world for a few precious moments before the tranquility returns. This is all precipitately detonated by the opening drama of “Mazeppa”, with its arresting opening chords and portentous stirrings of agitation leading to the remorseless drama of a wild and torturous captive horseback ride, Quang’s strength and agility ably suggesting by turns the hero’s desperate plight, his longing for release, and eventually, his triumphal redemption. And, in the wake of these heady heroics comes the alchemic magic of the following “Feux Follets” (Will-o’the Wisps), one of Liszt’s absolute masterpieces, famous for its demands on the player regarding velocity, tonal shading, finger-control and poetic evocation, all of which Quang achieves with meticulous differentiation and bewildering evanescent manifestation.

How different is the dark, mysteriously-voiced “Vision” which follows, a grim and black-toned G minor presence whose aspect takes on a proud glow from within under Quang’s fingers as the music’s heroic spirit is awakened and enlivened. Perhaps he isn’t as intensely visionary as Kentner or as granite-toned as Arrau in this music but, as in the following “Eroica”, he conveys in places as telling an awareness of the music’s poetry as its physical forcefulness – he grows the latter piece through its strong-willed opening flourishes, treating us to an intrepid journey from whimsical beginnings through a vainglorious display of valour, before circumspection proclaims that honour is satisfied. No such hint of heedfulness attends the next piece, however – the tumultuous “Wilde Jagd” beloved of German folklore as “Wild Hunt”, here given a tremendous, frenetic opening by Quang before settling to the chase in an almost carnival spirit, complete with a “hunting song”! The subsequent building-up of the music’s sheer physicality and strenuous vigour reaches cataclysmic levels in the pianist’s hands before it all seems to collapse in sheer exhaustion!

All of this leads to what seem to me the disc’s most remarkable performances, beginning with the heart-warming poetry of Quang’s playing of “Ricordanza” (Memories), a piece haunted by ghosts of memory depicted in the music’s piquant figurations and flourishes, shades of the past “filled out” with exquisitely-wrought manifestations – Busoni’s famous and incomparable “discovery of old love-letters” description of the piece is referred to by the pianist in his notes. As befits one of the great musical love-poems, Quang’s playing touches the heart of this listener for one, with its spontaneous-sounding evocations of remembrances couched in terms of a slow-moving, emotion-laden “dance” framed by frequent impulses denoting poignantly-suggestive things whose nature remains indefinite.

The following F Minor Study follows on its predecessor’s heels almost attacca – as well might a piece marked allegro agitato molto! Quang gives the oft-repeated opening figure more urgency than does Kentner, who keeps the figurations in trajectorial step with their overall context (by contrast Lazar Berman almost eviscerates the figures’ notes themselves with his rapid-fire delivery!). But how deftly Quang manages the midway transition back to the piece’s beginning, splendidly reiterating both the angst-laden declamatory theme and the return to the opening agitations, with those exciting running syncopations leading to the piece’s coup de grace!

I’ve written of the indelible impression made on me by this work as one wrought by “Harmonies du soir” – and so it’s fitting that Quang here brings the listener to a kind of apex of achievement with this study and its “mirror image” that follows, the equally remarkable “Chasse Neige”. But even now, fifty years after first hearing those opening notes of “Harmonies” sound their opening embrace that enfolds those impulses they give rise to, I still find myself wreathed in that same wonderment as nature’s bells are softly set ringing and then enjoined by a second theme to give full tongue in praise of creation’s beauteous manifestations – and here, nothing is forced or strained but wholeheartedly ‘’released” through the pianist’s obvious love of his subject and his palpable skills and sensibilities.

How prescient of Liszt to give the cycle’s last word to nature, leaving the listener with a sense of worldly impermanence, almost a “Sic transit gloria mundi” observation as the remorseless snows of “Chasse Neige” cover over all trace of the lives made so manifest throughout the rest of the pieces – Quang is totally at one with the composer, here, revelling in the overlapping surges of tone in the piece’s middle section and bringing off the concluding “claw-like” gesture of farewell at the end with suitable gravitas and finality.

Luu Hong Quang would do well to be proud of his response to this “marathon” challenge with, in his own words – “a true milestone in (an) artistic journey” – may we hope he might, before too long, undertake to put a proper girdle about the earth by enabling this astonishing work to live and breathe in concert for only a second time within these far-flung spaces of our own hemisphere!