Orchestra Wellington presents “PRODIGY”

Georges BIZET – Symphony No. 1 in C Major

Felix MENDELSSOHN – Violin Concerto in E Minor Op.64

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH – Symphony No. 1 in F Minor Op.10

Amalia Hall (violin)

Marc Taddei (Music Director)

Orchestra Wellington (Peter Clark – acting Concertmaster)

Saturday 12th April, 2025

Michael Fowler Centre

Wellington

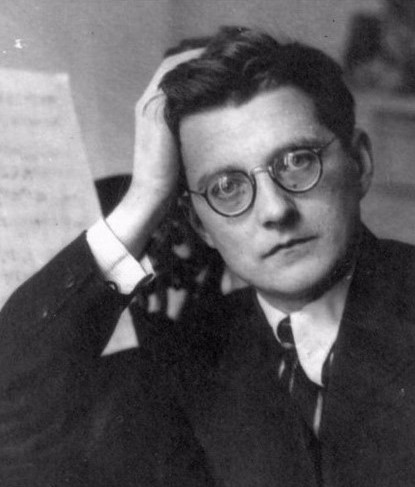

(pictured at right – Georges Bizet; below, Felix Mendelssohn-Barthody; and further below, Dmitri Shostakovich)

Orchestra Wellington spectacularly lived up to its long-established reputation for innovative concert programming with the first presentation in its latest series “The Dictator’s Shadow”, one doing rich justice to the youthful creative achievements of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whose fiftieth anniversary is being celebrated world-wide this year. This opening concert showcases Shostakovich’s remarkable First Symphony, written during 1925 while still a teenaged student at the Leningrad Music Conservatory, and achieving a sensational success, both at home with its Leningrad premiere (May 1926) and abroad, with the work receiving performances as far afield as Berlin and the United States the following year.

As a concert in itself, the scheme based on the idea of “Prodigy” could hardly have done better, even if any of the last three of the teenaged Mozart’s Violin Concerti could just as easily (and appositely) have been substituted for Mendelssohn’s famous E Minor Op.64 work as a vehicle for the gifted Amalia Hall to play – I must sneakily admit that I, for one, would have relished even more the opportunity to hear her play any of those last three Mozart masterpieces!). Still, the idea of using the Mendelssohn work (apart from the happy availability of such an accomplished soloist) was to bring to notice the composer’s own prodigious creativities with earlier works such as the Octet and the Overture to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, both of which were completed during Mendelssohn’s teens.

To complete the picture there was no happier way of demonstrating a young composer’s talent, inspiration and versatile technique than presenting the youthful (1855) Symphony of Georges Bizet – and though there were only the merest touches of greatness approaching the order of “Carmen” or “Les pêcheurs de perles” in this seventeen year-old’s enthusiastic concoctions of youthful endeavour, the overall impression of the music is that of a nature by turns vivacious and dreamily melancholic, equally at home in the town or the country, as portrayed by turns, in the various movements.

Marc Taddei’s spirited direction appropriately bounced the opening along, the high-spirited trajectories providing a lovely foil for the plangent beauty of the oboe’s floating second-subject lines soaring above the strings undulating patterns, then playing with the fanfare-like figures which frame the more lyrical sections, and the horn calls that both introduce and bid farewell to the movement’s development. After this, the slow movement’s dreamy, somewhat quasi-oriental meanderings were hauntingly voiced by the oboe after the most enchanting of openings (where did the young genius conjure up this mood from?) had been brought in by the strings. Just as engrossing was the ensuing string fugato with which the oboe then adroitly wove a reprise of the opening melody – had Robert Schumann been alive to hear this sequence, he might have uttered a judgement to rival his famous appraisal of one of Chopin’s youthful words many years before – “Hats off, gentlemen – a genius!”.

I’ve always loved the Trio section of the charmingly rustic Menuetto-Scherzo which follows, not least because of what I’ve always thought was Bizet’s “gently poking fun in a Beethoven-like way” gesture at the wind players who have the Trio’s melody and repeat it a fourth higher at Fig.8 (in my score). Oboe and clarinet on all the recordings I’ve heard except for one play a delightfully astringent-sounding B-natural in that phrase instead of a B-flat, perhaps to indicate (as Beethoven did with his village band music in the “Pastoral” Symphony), that the players might not be fully up to the music’s demands! Here, I seemed to hear (if my ears were serving me correctly), that the wind-players were playing a B-flat, which of course sounded a lot more mellifluous, but not nearly so tangy and rustic! I have, as I’ve said, recorded evidence for both versions being acceptable, but I do wonder what the composer ACTUALLY wrote!

The finale was an exhilarating, momentum-plus performance, Taddei and his players bringing out the music’s fleet-fingered energies in a toe-tapping way, but giving attention to the shapes and trajectories of the melodies as well, contrasting the “perpetuum mobile” of the opening with the grander, more ceremonial second theme, and a more sinuous refrain, a more vulnerably human, song-like tune with which to “people” the soundscape (the “melodic gift” already strongly in evidence in the young composer!)

Oddly enough Bizet seemed to never give the work another thought as an entity, confining his interest to “cherry-picking” bits of it for use in more “serious” works, such as the opera Les pêcheurs de perles and his music for the play LArlesienne. Thanks to the French musicologist Jean Chantavoine who in 1933 published an article regarding the work’s existence, the symphony came to the attention of the conductor Felix Weingartner, who gave the work its belated premiere performance in 1935, earning for it a “wunderkind” status in league with the efforts of Mozart, Mendelssohn, Rossini and Shostakovich.

But next was Mendelssohn – and if the work chosen this evening was definitely not a “wunderkind” work in terms of years, it still evoked memories of hearing for oneself at another time those two outrageously precocious pieces which have for all time identified their then teenaged composer as one of nature’s creative marvels, the Octet for Strings and the Overture to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”. This was the E Minor Violin Concerto, for many listeners the work that epitomises the romantic instrumental concerto with its manifest qualities, and one for which tonight’s soloist. Amalia Hall (the orchestra’s regular Concertmaster), seemed a near-ideal choice as its performer.

I’ve certainly not heard a more silvery-toned performance, one whose gossamer finish seemed in places almost unearthly, especially so in the rapid figurations when the notes seemed to “spill out” from the instrument like stardust from a comet arching across a firmament, with the couple of minor intonation stresses deserving the description (coined by a similarly entranced commentator in another, different context) “spots on the sun”. One might also occasionally have wanted a shade more tonal projection in places from the soloist; but to look for something different would be to besmirch the magic we were fortunate to find ourselves caught up in on this occasion – and so we contented ourselves with the integral state of things as part of the excitement and wonder from both soloist and orchestra.

The music itself is too well-known to annotate at length – enough to say that the musicians here aptly probed the “character” of each of the work’s movements, filling the ambient spaces with appropriately vibrant tones and gesturings across the instrumental spectrum, More of a dialogue than a contest throughout, the interaction between Hall and her conductor and players transmuted the first movement’s questings, proposings and bargainings into concordance with the enticing sweetness of the slow movement’s exchanges before giving the exuberance of the finale its head, violinist, conductor and orchestra revelling in the freely-shared elation of the work’s full expression.

Our readily-wrought appreciation of Amelia Hall’s playing was further enhanced by an encore item she performed with Peter Clark, her stand-in this evening as Concertmaster. This was a duo written by the Polish composer-virtuoso Henryk Wieniawski, his Etude-Caprice Op.18 No,4, in which the playing of both musicians was as remarkable for its delicacy and finesse as for its brilliance – a true sweetmeat of a bonus!

Casting about for ways to characterise the very “two different worlds” kind of ambience which grew straightaway from the sounds of Dmitri Shostakovich’s singularly remarkable First Symphony, one has to find words for a “new era” of expression – and in this case, one with something of an almost hallucinatory quality in its music’s rapid-fire contrasts of atmosphere, outlook and motivation. One learns with no surprise that the composer spent much of this time earning a living as a cinema pianist, developing in the process a kind of penchant in his music for rapid movement and change, the introduction of disparate elements, and an almost expressionist delight in their surprising interactions.

These thoughts summed up something of the story of the Symphony’s first movement, presented here by Marc Taddei and his players with, in the wake of the concert’s first-half respectabilities, almost mind-boggling aplomb. It’s all superbly etched in, with the changes of pace and mood here nonchalantly and there explosively registered (though clearly articulated, whatever the voice), and the overall energies of the transitions driving one’s sensibilities on until reaching the droll “did we dream you or you us?” fragments of out-and-out wonderment at the end that had previously tumbled past us all through the plethora of incident carried by the music.

By contrast, the second movement was here kept constantly and brilliantly on the move, either in a helter-skelter or a trance-like, sleepwalking kind of trajectory, each of which abruptly changed as if Shostakovich was following a private movie-showing (here, Rachel Thomson relishing her occasional “cinema-pianist” role with gusto!). Or, perhaps, we were being asked to reimagine something grimmer – sequences of flight and agitation followed by funereal processions over desolate battlefields still resonating with crushing piano-chord hammerblows……

The music’s Lento mood darkened and deepened, with Taddei drawing from his players a remarkable soundscape of sorrow, with beautiful oboe and ‘cello-playing, taken up by the horns and strings, the repeated portentous brass call heightening the mood of tragedy – the performance brought out the music’s potent “funeral oration” character, moments of harshly unfettered despairing alternated with bleak, desolate voices, anticipating the Shostakovich of the great and harrowing symphonic adagios to come!

And so to the fourth movement, begun with a snare-drum crescendo which seemed at first an isolated, even fatuous gesture of promise, but which planted a rebellious seed in the Lento that returned, bearing its brass, wind and cello musings – suddenly, trumpets and lower strings were igniting the clarinets and upper strings, and whirling us away on a kaleidoscopic journey of contrasts too numerous and varied to fully describe, but remarkable to experience in a single span of time! There seemed nothing which daunted these players and their valorous maestro – we were transported from the music’s deep recesses of gloom to its near-frenetic expression of exhilaration as the composer’s “end-game” imaginings were given their head in this engrossingly unpredictable but ultimately edifying ride!

If Orchestra Wellington continues to delight us with anything like the same adventurous spirit, emotional engagement and instrumental brilliance as we heard in this first “The Dictator’s Shadow” concert, the remainder of the series will, for me, be well-nigh unmissable! Full marks to all involved for such intelligent and innovative programming and for the sheer elan of execution (oops! – that word just slipped out, Comrade! – sorry!) of some glorious music!!