MAURICE RAVEL – Opera in One Act – “L’Enfant et les Sortilèges”

(libretto by Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette)

Students and staff of Te Kōkī / New Zealand School Of Music

Victoria University of Wellington / Te Herenga Waka

– in association with Toi Whakaari / NZ Drama School

Sara Brodie – Director

Therese Hanaray – Assistant Director –

Martin Riseley – Conductor and Head of Strings

Kathryn Mosley – Chorusmaster and Head of Collaborative Piano

Grace O’Brien – Set and Costume Design

Alex Fisher – Lighting Design

Brooklyn Saunders – Production Manager\

Cast and Musicians

Charlotte Secker – The Child

Francesca Fagan – The Mother, the Cup

Charle Rainey – The Armchair, the Male Cat

Greer McCarthy – The Bergère Chair

Joseph Clinton – The Grandfather Clock, a Tree

Elias Nguyen – The Teapot, the Arithmetic Teacher, the Tree Frog

Chu My Duyen – The Fire, the Nightingale

Cadence Chung – A Shepherd, the Dragonfly

Eve Parker-Groves – A Shepherdess, the Bat

Emilia Gray – The Princess

Eunice Ng – the Female Cat, an Owl

Tiaki McArdle – the Squirrel

Members of Te Kōkī Orchestra, New Zealand School of Music

The Hannah, Hannah Playhouse, Cambridge Terrace, Wellington

Saturday 6th September, 2025

Maurice Ravel’s only operatic ventures during his remarkable compositional career were two smaller-scale works, written and performed a number of years apart – firstly, in 1911, came the brilliant, tongue-in-cheek satire “L’Heure espagnole” (The Spanish Hour), and then (in the wake of the Great War) succeeded by an ostensibly less “adult” but more deeply-felt creation, “L’Enfant et les Sortilèges” (The Child and the Magic). The latter is a work whose explorations of a child’s world don’t spare the listener occasional moments of cruelty, darkness and sorrow touched upon in places by the story. The original idea for the scenario came from the author Colette, whose first intention was for the story to be told in the form of a ballet. Ravel, however, had been persuaded that an operatic successor to “L’Heure espagnole” was needed, and had meantime been stimulated by the “new wave” of musicals and revues with new dance-forms by composers such as Gershwin. As the new work took shape so too did the composer’s enthusiasm for these “operetta-style” features take wing, to the point where Ravel could enthusiastically describe preparations for the first performance in Monte Carlo in March 1925 with the words “…an extraordinary production – the roles are numerous and the phantasmagoria is constant!”

This 2025 realisation was co-ordinated by Jenny Wollerman, Head of Classical Voice at Wellington’s Te Koki School of Music, bringing together students and staff members from both the Music School and Toi Whakaari (NZ Drama School). It joins a number of memorable productions by the Music School over the years, with, to my mind Benjamin Britten’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and Verdi’s rarely-performed “Il Corsaro” readily resonating in my memory still, as I write this.

Director Sara Brodie’s production at “The Hannah” most appropriately celebrated the work’s one-hundredth birth-year, echoing triumphantly the composer’s enthusiastic description of the original event with its “continually and intimately-mingled” dancing on the part of the singers. She made splendid use of the venue’s multi-levelled and -entranced features, encapsulating the audience within bevies of singer/actors on two sides and musicians on the remaining two, so that we felt at times as much participants in as observers of the story’s by turns dream-like, quixotic, unpredictable and heart-warming expositions.

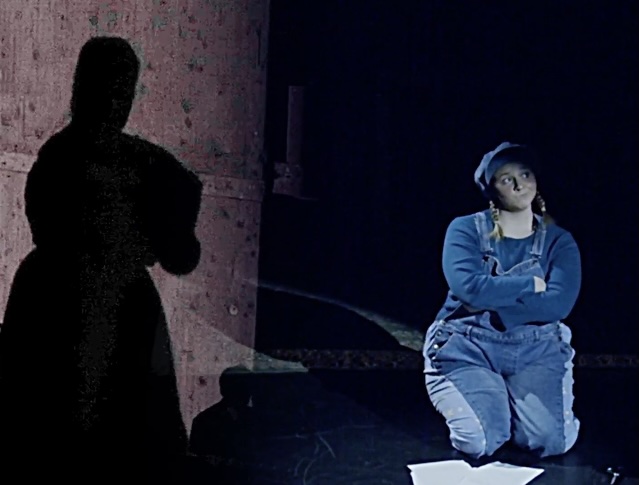

Straightaway, Ravel’s innocently sinuous Prelude drew us into the dream, a kind of twilit world of light and shadow, suggesting the “old-fashioned Normandy country home” of Colette’s setting, complete with armchair, fireplace and Grandfather clock – even the shadow cast by the offstage character of the Mother effectively reinforced the “old-world” atmosphere and its sense of well-established order.

These things were, of course then shattered, literally, to pieces, firstly by the disobedient Child’s tantrums in destroying or disabling almost everything she could find in the room, then by the fantastic “coming to life” of many of these same objects, each bent on demonstrating to the Child her wilfulness, selfishness and even cruelty in carrying out her unthinking acts of destruction and unkindness to both creatures and objects that co-existed in her world.

Even when escaping to the garden, the Child’s relief was short-lived, as the trees themselves confronted her with the “wounds” she had subjected them to, her guilt intensified further by a dragonfly whose mate she had killed so as to pin to a wall, and also a squirrel she had enclosed in a cage. Overcome by shame, she called out for her Mother, infuriating the creatures, who then attacked her – in the subsequent melee, a squirrel was wounded, and the remorseful Child confounded the creatures present by dressing the squirrel’s wounded paw. Moved by this change of heart on the part of their previous tormenter, the animals and trees then sang “Il est bon, l’enfant, il est sage” (The Child is good and wise”), at the end of which she was reunited with her (still offstage) Mother.

The power of emotion in Ravel’s music never ceases to amaze me, as here – above all else, it’s the depth of sadness in the music, including that expressed by the Child for her much-loved but now-forsaken “Princess” which indicated the composer’s capacity for depth of feeling behind the accustomed “coolness” of the mask. But more bleakly and tragically we shared the Child’s confrontation with her part in the dragonfly’s loss of its mate and the squirrel’s equally heart-rending loss of its freedom, moments which cumulatively “seeded” the animals’ final forgiving chorus to produce a lump-in-the-throat effect which for me flooded those concluding ambiences, and was here achingly, almost cathartically realised by the singers and players.

The set’s atmospheric qualities buoyed up every scene, sometimes amusingly, sometimes poignantly and sometimes startlingly, invariably making the point to the Child that each irruption was the consequence of her doings. As the Child in the Blue (Second) Cast whose performancce I attended, Charlotte Secker was superb in both her singing and acting delineations of her character’s situation, and in her reactions to her accusers, taking us on a kind of journey through her various stages of realisation. In each instance she demonstrated fear, guilt and remorse in appropriate and ever-changing proportions as the encounters clicked over, her voice eloquent both in exclamation and song (particularly so in her serenade to the Princess).

As for her various accusers, every scene had a particular flavour of characterisation brought out either in voice, in demeanour or in both, by each of the single protagonists or groups. In every case the physical characterisations were admirable, the olde-world aspect of the pair of chairs, “LeFauteuil” and “La Bergere”, the petulant Grandfather Clock, the quixotic Teapot and Cup, the excitingly fearsome Fire, the pastoral charms of the Shepherds and Shepherdesses, and the beautiful Fairy Princess (for me, shades of the “Fairy” in the “Pinocchio” story I often read as a romantically-inclined child!), not to mention the manic, attention-grabbing Arithmetic teacher and his well-drilled coterie of numbers! – such brilliant singing, movement and staging!

Two wonderfully-characterised Cats then made the most of their delightful “rubber ball” scene, managing to be suggestive together (without resorting to Andrew Lloyd-Webber-like vulgarity!) – before the story took the Child outside to the Garden. Of course there was no respite there, with everything, trees, insects and animals, testifying to the by-now remorseful Child’s cruel and insensitive treatment of Nature, with even the group of bats’ beautifully-lit movements and the frog group’s lilypad cavortings suggesting flight and escape as much as play, and the dragonfly’s and squirrel’s vocal contributions in particular so very tragic and touching and beautiful.

This was a classic “ensemble” affair, in which everybody – singers, musicians, directors, designers, stage-managers, technicians, and enablers of all kinds – gave of their best to bring to fruition something which should resonate in memory for a long time to come! – very great credit to Sara Brodie whose direction of it all made possible such a captivating operatic experience.