SHOSTAKOVICH AND MOZART

Helene Pohl and Anna van der Zee (violins), Rolf Gjelsten (‘cello) and Nicholas Hancox (viola) play Shostakovich

Helene Pohl and Anna van der Zee (violins), Rolf Gjelsten (‘cello) and Nicholas Hancox (viola) play Shostakovich

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH – String Quartets – No. 11 in F Minor Op,122

No. 13 in B-flat minor Op,138

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART – String Quintet in D Major K.593

The Chamber Pot-pourri Ensemble

Helene Pohl, Anna van der Zee (violins)

Nicholas Hancox, Julia Joyce (violas)

Rolf Gjelsten (‘cello)

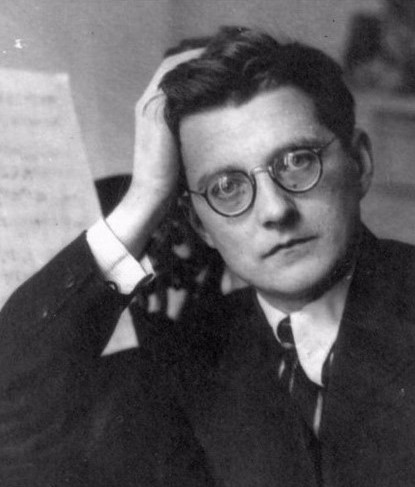

SHOSTAKOVICH -String Quartet No. 11 (1966) – in memory of Vasily Pyotrovich Shririnsky

Introduction, Scherzo, Recitative, Etude, Humoresque, Elegy, Finale

String Quartet No. 13 (1970) – dedicated to Vadim Vasilievitch Borisovsky

(Quartet in One Movement)

Adagio, Doppio movimento, Adagio

MOZART – String Quintet in D Major K.593 (with Julia Joyce – viola)

The Long Hall,

Roseneath, Wellington

Saturday 19th April, 2025

This was the second 2025 “Comfy Concert’ at Roseneath’s “The Long Hall”, part of a benefit series to assist various charities, on this occasion spotlighting the inspirational Arohanui Strings (of which violinist Helene Pohl is the Patron), a visionary Sistema-inspired music-teaching organisation and registered charity based in Lower Hutt. Founded in 2010 by professional musician and El Sistema advocate Alison Eldridge in the belief that all children have a right to a music education, this programme has offered musical instruction to more than 4000 children in some of Wellington and Hutt Valley’s most economically challenged communities.

Though the concert may have been relatively short in performance-time, it surely made amends for any brevity-related aspersions in terms of “moments per minute”. Each of the three works displayed a distinctively wrought sound-world whose singular qualities nonetheless found common cause in their surety of utterance and burgeoning character. And what we heard throughout the afternoon was an “every note counts” quality for which musicians such as Helene Pohl and Rolf Gjelsten have earned unstinted renown over their quartet-playing careers to date, and which their colleagues, Anna van der Zee, Nicholas Hancox and Julia Joyce were readily able to replicate in partnership over the concert’s duration.

In an earlier “Chamber Pot-pourri Ensemble” presentation in this same venue a month previously, we’d heard another Shostakovich String Quartet, the Ninth, along with a new work by Chinese composer Gao Ping which was dedicated to Shostakovich’s memory to mark this 50th anniversary year of his death. On that occasion, the second violinist was Monique Lapins, and the violist Chris van der Zee. Given the remarkable variety of the quartets given thus far in this survey, it might be that Helene’s and Rolf’s necessarily pragmatic choices of colleagues for each occasion could arguably add to the music’s appeal, piquantly suiting the “living dangerously” aura around Shostakovich’s own creative efforts in general. Of course, by the time he had come to writing quartets the composer had ostensibly survived his most hazardous brush with the tyrannical Soviet leader Josef Stalin (specifically over the latter’s reaction to the opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk”), and had since embarked on a series of works which he hoped would give rise to less scrutiny than his more “public” works.

By the time he came to write the aforementioned Ninth Quartet it was 1964, and the composer had appeared to have largely “broken free” from the constraints of a system that had told its creative artists how they should make their art. A Tenth Quartet was written in the same year, and the Eleventh was begun the following year. The latter was the first of a group named the “Quartet of Quartets”, and written for the violinist Vasili Pyotrovich Shirinsky, a member of the Beethoven Quartet, the ensemble to whom the composer came to entrust the premieres of all of these works right up to the Fourteenth Quartet. Shirinsky actually died before the work’s completion and the remaining players had seriously considered disbanding the quartet – however Shostakovich had argued for the group to continue, as he maintained the group had “acquired the status of a national institution”.

Rolf Gjelsten introduced this work, commenting most tellingly that it was “great string quartet music which created powerful effects”. The work consisted of seven closely-connected (all marked attacca) miniature movements, beginning Andantino with a short, rhapsodic violin solo, here, beautifully-focused throughout all its appearances by Helene Pohl – answered and echoed by her colleagues, largely expressing a kind of calm acceptance, briefly spliced by a “wrench of agitation” but returning to an integrated kind of poise. The first violin moved things along with the Scherzo – a repeated-note theme, played more legato than pointed and playful, followed by the viola and ‘cello, “dug in”, and with occasional stinging upward glissandi! Together, the violins gave the motif a sinister element by beginning the phrases in fourths, “worrying” the notes insistently – after this all died away, the players suddenly “attacked” the Recitative, with stinging opening sounds, and dissonant resoundings, briefly playing some uncannily ambient “Vaughan Williams-like” contrasting harmonies before returning to the opening, though letting the “stinging” attacks gradually disperse.

Again, the mood suddenly changed with the “Etude”, the solo violin embarking on a sinuous whirling-dervish episode, to which the other players reacted almost dreamily at first, but then almost grotesquely as the solo violin intensified its flailing attack, the others enacting a kind of drunken sailors’ dance, before anarchy broke out, with the ‘cello joining the fray, as if possessed of its own accord! Out of nowhere, it almost seemed, came the Humoresque, with an urgent, warning-like two-note ostinato-like figure from Anna van der Zee’s violin, to which both violin and viola took fright (Nicholas Hancox’s viola matching Helene Pohl’s violin in sheer ghoulishness of tone) – such transfixing sonorities made it seem as if we had taken a brief but scarifying turn into a Little Shop of Horrors!).

The Elegy brought sense and feeling to the proceedings in spadefuls – ‘cello and viola first dark and sombre, but still sonorous and affecting, then the second and afterwards the first violin returning us to daylight, their sounds emoting like prisoners from dark places espying light. And so the Finale was on us, with the players teasing out by turns the work’s past themes, the process filled with conflicting emotions as the memories returned on the various instruments, and ending with Helene Pohl’s violin reaching the work’s final high C with a variously pre-constituted sense of fulfilment….

Aptly chosen as a companion-work for this concert was the similar-but-different Thirteenth Quartet, of roughly an approximate length though differently constituted, having a single movement, albeit with contrasting episodes – an ABA structure similar to Bartok’s Third Quartet. It’s dedicated to the Beethoven Quartet’s violist Vadim Vasilyevich Borisovsky, who had just retired, leaving his replacement Fyodor Druzhinin to take part in the premiere in December 1970. Shostakovich was by then a sick man, having suffered a heart attack shortly after the Eleventh Quartet’s premiere in 1966, and was receiving treatment throughout 1970 at an orthopaedic clinic – the new work’s largely pessimistic outlook stems from his awareness of approaching his life’s end. It’s reinforced here by a late inclusion in the outer movements of some of the composer’s music for Grigori Kozintsev’s film “King Lear”, originally conceived as “Lamentations” for a string quartet.

In introducing the work Helene Pohl made mention of the remarkable “jazzy” elements in the second part, quoting the composer as saying to somebody “I’ve written a short little quartet – with a “joke” middle!” – a sequence which another commentator had, I read, characterised as “a jam session from Hell”, and which came across as a grim “dance of death”, the composer joining forces with his great predecessor, Musorgsky, in regard to the latter’s “Songs and Dances of Death”.

Appropriately, it was the viola which began the work, a sorrowful solo with others joining in– bare, astringent sounds with occasional dissonant note combinations. The players took their time, with the violin taking the lead working up to a “crying out” sequence with the second violin, and encouraging the viola and ‘cello to join in. When the meditative tone resumed I caught a further reminder of a bleak “Vaughan Williams” voice in the harmony, along with the unsettling half-tone dissonances.

Helene had demonstrated to us the repeated-note phrase that began the more volatile middle section, emphasising for us its mournful rather than playful character with more legato-like phrasing. The murmuring lines from the others developed into harsh, stabbing chords set against an angular descending seventh figure from Nicholas Hancox’s viola – which in turn lead into a wonderful, once-repeated “augmenting” chord, the instruments joining in stepwise, punctuated by the repeated-note figure, and the viola’s falling-seventh declamations! – jaw-dropping stuff!

What developed next seemed to me almost Dada-like! – a viola tremolando, pizzicato figures from the others, and rapid-fire exchanges of the same activated the ‘cello with Rolf Gjelsten giving us a “grooving-along” kind of running jazz pizzicato, prompting the violins into a “cool” dotted- rhythmed note pattern to which the players occasionally beat the wood of their instruments with their bows in syncopated strokes! – these jazzy, syncopated rhythms proceeded to “fight” against mournful, downwardly-sighing lines from the viola, which grew to resembling a kind of all-out aerial attack on the scurrying inhabitants below! – all so visceral and palpable!

Violin pizzicati provoked a full-blooded response from the cello, whose mournful lines eventually prevailed against the jazzy rhythms, with murmuring lines gathering to subdue the ground zero activities and establish an uneasy, ghostly, tremolando-like calm – a couple of bleak pizzicato repeated-note whimperings from the violin stimulated another startling, though short-lived outbreak of the repeated note pattern before it too gave up the ghost. All of this was thrill-a-minute stuff, brought into being with an immediacy that, especially in such unprepossessing settings, simply took the listener’s breath away!

Out of the thicket emerged sighing violin lines and trenchant ‘cello responses, with the violin ascending heavenwards in search of some form of redemption/oblivion, its companions resonating in support, the exchanges again briefly sounding that distinctive “Vaughan Williams” ambience that brought to my mind the latter’s Sixth Symphony – most affecting! Then came the viola’s solo, augmented by cadaverous tappings from the second violin – after which the viola continued, joined by the first and second violins in an extended B-flat which slowly burgeoned towards a piercing climax.

Julia Joyce (viola) and the Chamber Pot-pourri Ensemble play Mozart

Julia Joyce (viola) and the Chamber Pot-pourri Ensemble play Mozart

The intrinsic greatness of Mozart’s music would, of course, have easily survived a cheek-by-jowl placement with these twentieth-century goings-on intact, but the interval break was nevertheless appreciated at that point! It did give one the chance to ponder what we had heard in relative isolation, and especially apposite given the cultural “head start” enjoyed by an eighteenth-century classic work when pitted against a later “arrival”. I had enjoyed my own particular “first encounter” with Mozart’s K.593 many years ago, courtesy of a fellow bus-driver I befriended during my “mis-spent youth” period of exploration! This particular individual was a Rastafarian-like figure, complete with dreadlocks! – one who completely belied his appearance by frequently conversing with me about art, literature and music, and ultimately making a present for me of a recording of two of the Mozart Quintets in question, one of which was K.593 (and which he himself adored!).

It was a “head-start” of sorts for me with this work, of course, which I grew to love all the more – and on a later, box-set pressing of the same recording (the stereo Amadeus with Cecil Aronowitz) I also got to know the “alternate version” of the finale’s opening, the phrase written chromatically, rather than in stepwise fashion, and which is now recognised as the “authentic” opening – Helene Pohl pointed this out, playing both versions for our delight, though stopping short of proposing an “audience vote” on the matter!

It was one of a number of delights associated with this performance, another being Rolf Gjelsten’s engagingly individual way with the ‘cello phrase that began the work, repeated in different keys in ways that made the player on my Amadeus recording sound relatively po-faced and non-commital! Also, I’d never before properly “connected” this episode with the music of Haydn, despite owning recordings of things like the “Drum Roll” and “London” Symphonies for years and years, works with similar kinds of slow introductions, and with the same returning at the end of the opening movements! And finally, the presence of the NZSO’s principal violist, Julia Joyce, in the ensemble gave the performance a wonderfully “burnished” glory of exchange, particularly evident in the slow movement, with its frequent conversational violin/viola passages – all very theatrical, as well, I thought, with the tuttis bursting almost to full with expression.

A quickly-flowing Menuetto followed, less about “beats” and more about emotion ”flowing like oil”, as the composer would have said, and, with the Trio, a showcase of ascending arpeggios, a veritable welter of them on at least two occasions, both collegial and celebratory. As, of course, were the wry interlockings of the finale’s workings, where the sheer contrapuntal elan of the writing becomes an “Anything you can do” kind of musical feast with an “Of course!” series of rejoinings, the exhilaration of matching knife-edged impulses and resplendent tones a glorious display, and one for all of us to savour and remember for a long while to come.

Michael Steward and the Tudor Consort at Wellington Cathedral of St.Paul (photo: Cassandra Wang)

Michael Steward and the Tudor Consort at Wellington Cathedral of St.Paul (photo: Cassandra Wang)

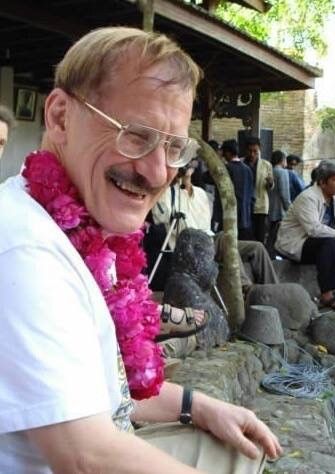

Donald Maurice (conductor) and Inbal Megiddo (‘cello) rehearse Shostakovich with the Wellington City Orchestra, December 2024, at St.Andrew’s Church, Wellington

Donald Maurice (conductor) and Inbal Megiddo (‘cello) rehearse Shostakovich with the Wellington City Orchestra, December 2024, at St.Andrew’s Church, Wellington

“Turtle Time” with speaker Jonathan O’Drowsky, and conductor Robert Oliver.

“Turtle Time” with speaker Jonathan O’Drowsky, and conductor Robert Oliver. Some of the performers at the conclusion of “Jack@80” at St. Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace Church, Saturday 12th October, 2024

Some of the performers at the conclusion of “Jack@80” at St. Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace Church, Saturday 12th October, 2024 Wellington City Orchestra presents:

Wellington City Orchestra presents: Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

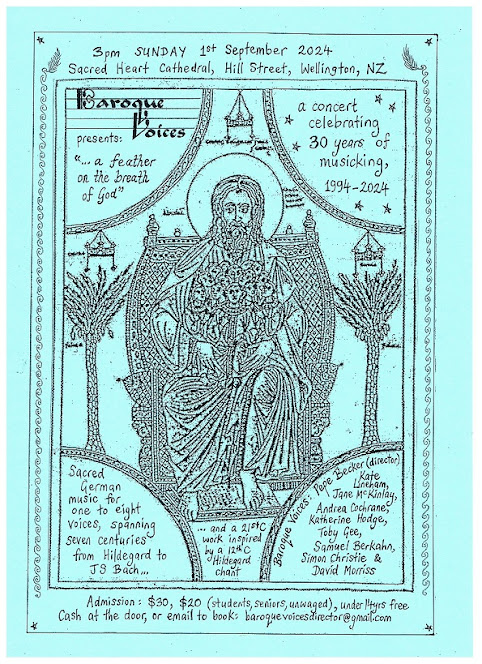

Quang Hong Luu Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach –

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach – Baroque Voices 2024

Baroque Voices 2024