Wellington City Orchestra at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, with Diedre Irons (piano), Brendan Agnew (conductor), and Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor)

Wellington City Orchestra at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, with Diedre Irons (piano), Brendan Agnew (conductor), and Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor)

SAI NATARAJAN – In This Corner Of The World

LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN – Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor

DOUGLAS LILBURN – Symphony No. 2

Diedre Irons (piano)

Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor – Natarajan)

Brendan Agnew (Conductor)

Wellington City Orchestra

St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Wellington

Sunday, 7th December, 2025

Now this was a treat for any concertgoer relishing the thought of something old and something new, combining an easeful kind of familiarity with more challenging musical terrain, as well as setting home-grown worlds in a wider context. Wellington City Orchestra’s programme enterprisingly opened up for us here-and-now impressions of creative forces at work in Aotearoa, before time-travelling us to Beethoven’s world and back again, and finally giving us a time-in-motion slice of “being” at a significant emerging point in our own colourful history. The sounds we heard spoke volumes for each of these times and places – it was something of a proverbial journey!

Different people participated in this process, and in different ways – we were welcomed to the concert at its beginning by Rowena Cullen, the orchestra’s President who’s also a member of the violin section, after which today’s conductor Brendan Agnew firstly paid tribute to a recently deceased orchestra member, Mark Hill, and then introduced today’s concert’s assistant conductor, Virginie Pacheco, who directed the concert’s opening performance, a heartwarming piece by youthful composer Sai Natarajan. At its conclusion Brendan Agnew then bade us welcome pianist Diedre Irons to the stage to deliver her Beethoven concerto performance. Like the “players” in Shakespeare’s “Ages of Man” all of these individuals had, by their own lights, a special part to play in the panoply.

Beginning the concert charmingly and sonorously was a work written by emerging freelance composer Sai Natarajan, from Palmerston North, one called “In This Corner of the World”. With Assistant Conductor Virginie Pacheco (the first to actually hold this title with the WCO) at the helm, we were transported at the beginning to the Manawatu plains, with Sibelius-like wind impulses sounding across the deeper murmurings of those open spaces, all the while engendering awakenings of activity, the thrustings and resoundings suggesting iceberg-tips of the “absolute powerhouse of artistic and musical talent” that abides in the region.

The music gathers itself and epically “pushes out” this landscape, contrasting numerous “forest murmurings’ with attention-grabbing percussive scintillations, a recurring motif resounding in one’s attention as the brass give us some Lilburn-like reminiscences suggesting the inherent “musicality” of natural rhythms. My own experiences as a born-and-bred Palmerstonian responded to the composer’s recognition of “artistic toiling” in modestly-appointed, yet still-resonating hatcheries of human productivity in all fields of expression. I remember watching as my parents and their contemporaries set examples for us of partaking of things resulting for some of us in what Sai Natarajan calls an artist’s “joys, struggles, disappointments and triumphs”, and from which modest origins still brought forth “beauty and joy” in the doing, and occasionally even something enduring and worth celebrating – as this this great-hearted piece certainly was!

Happily, “In This Corner of the World”, after being premiered by the Manawatu Sinfonia in 2024, was recorded earlier this year by the NZSO as part of their annual NZ Composer Sessions initiative. I would imagine we haven’t heard the last of this intuitive, versatile, and delightfully communicative composer.

The programme’s suggestion of a wider context of human creativity was hinted at by the music of a composer whose output for many people epitomised a kind of universality of utterance, Ludwig van Beethoven. His Third Piano Concerto is a kind of bridge-work between the classical and romantic eras, a realm which Mozart had also occasionally explored in music written in a similar key, but one more fully and dramatically furthered by this and other works by Beethoven.

Having splendidly recorded all of the composer’s piano concertos, and frequently played them in concert Diedre Irons was the ideal soloist to realise the “sturm und drang” of this work, aided by a suitably dark-browed accompaniment from the orchestra, with conductor Brendan Agnew on the podium. The opening was the orchestra’s alone, strongly-focused and well-detailed, to which the soloist responded with suitably dramatic contrasting gestures – it wasn’t all high drama and theatricality, with the second subject group almost playful in intent in places under Irons’ fingers, but leading back to a stern recapitulation by the players under Agnew’s direction and a properly virtuoso performance of the solo cadenza. Here, Irons was in complete command of the drama and volatility of the writing, bringing out the almost ghostly ambiences of the instrument’s return to the world of interaction in the movement’s darkly-enigmatic coda.

One of the most beautiful of Beethoven’s slow movements followed, with piano and orchestral passages delighting the ear, and the interchanges expressing a heartfelt “communal” sense of expression. Irons’ voicing of the decorative poetic utterances made every impulse a joy, and the winds and strings in particular matched her ardour – though the strings’ pizzicati could have been a tad firmer in places as they were near to inaudibility, so sensitive was their response! Particularly lovely were the last few interactions, the strings tender phrasings and the piano’s “haunted” chordings all underpinned by dark wind-and-brass murmurings before the latter echoed the piano’s final descending notes and brought in a final single chord – magical!

I loved the insouciance with which Irons then started the finale’s ball rolling – but the orchestra was ready for her, picking up the traces of the trajectories and ready to do its bit with the first big tutti – what great exchanges between orchestra and piano with those mighty chords and flourishes! A lovely clarinet solo introduced and elaborated on a new episode, and a string fugato followed, after a while beginning to loosen at the seams, but managing to complete the task as the pianist jumped in and steadied the rhythms! The recapitulation was strong and purposeful, as was Irons’ final grandstand solo flourish before the coda’s cheeky beginning, with truly spectacular piano-playing and a suitably vigorous audience response.

She was accorded a richly deserved tribute from all, but had not done with us yet! To our delight she sat back down at the piano and began the deliciously droll F Minor Allegro moderato dance from Schubert’s adorable Moments Musicaux. It was playing in which every note resonated and every impulse “choreographed” its own sound, inviting parts of us by turns to listen and sing and dance in our minds – and the moment towards the end when the final line impishly turned to F Major seemed as if the music was suddenly smiling at us and telling us to forget our troubles – magical piano playing!

An interval saw the piano further “magicked” to one side, leaving more space for the players to resound the strains of one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s most significant musical compositions, Douglas Lilburn’s Second Symphony. Completed in 1951, this iconic work had to wait until 1959 for its first public performance. Part of the problem was the country’s National Orchestra still being in its relative infancy (it gave its first concert in 1947) and its early conductors were certainly reluctant at that time to “take the plunge” with anything as off the beaten track as a locally-produced symphony – rather, they were set upon establishing the standard repertoire. The composer’s First Symphony had been an earlier casualty, completed in 1949, and premiered in 1951, to be then ignored for a further ten years. It wasn’t until the advent of John Hopkins as the National Orchestra’s Principal Conductor in the late 1950s that Lilburn’s music began to be performed more regularly – the composer’s gratitude was such that he went on to write a Third Symphony in 1961 and dedicate it to Hopkins!

The Second Symphony has always been associated with quintessential aspects of New Zealand life and landscape. What the composer referred to as “the imponderables” of the natural world feature strongly in the work – contrasts of light and shade and the vagaries of weather are prominent characteristics of the music’s different ambiences. Human influences are also a factor – in the second movement Lilburn immortalised what he described as the ”nasal and tangy” cry of Wellington’s Evening Post Paper-boy’s call, heard as he passed through the capital en route to or from the South Island. Others have commented upon the “search for identity” aspect of the music in the other movements, particularly in the third “Introduction”, where the “frontier” aspect of the environment seems somewhat remote and forbidding and essentially solitary. The music’s angst-like textures and ambiences seem to reflect struggles associated with a 1950s “coming of age” in artistic and other matters, one which the final movement translates into more positive and robust gesturings. I must here admit to a degree of dissatisfaction with the “Introduction” movement regarding its brevity – though expertly crafted, it doesn’t for me go far enough or even resound sufficiently within its existing parameters, eluding the feeling of a truly epic statement of being (it’s significantly shorter in scale than both the first or last movements!) – or have I been listening to too much Mahler or Bruckner or Shostakovich of late?

But to the beginning – beautifully and wistfully opened by the strings the first movement also featured buoyant solos from oboe, clarinet and flute, with the horns in atmospheric alignment. The strings, winds and brass raised us to the heights mid-movement with the horns having a wonderful “Carl Nielsen” moment (I once got taken to task by Lilburn himself for suggesting the merest connection of him with that composer!), and the timpani adding to the music’s “epic” quality before the strings, with the oboe supported by the horns, bring the movement to a relatively placid close. A pity the St.Andrew’s acoustic had difficulty sorting the dynamics, with the brass, to my ears sounding a bit lost in the mid-movement tuttis’ welter of sound!

Better-realised was the Scherzo, a more nimble, less weighty sound, the oboe doing a great job with the perky theme, and the brass and timpani lively at the climaxes. The other winds did splendid things with their variants of the theme, but the most nostalgic moments were the cellos’ introduction of the “paperboy” theme, and the strings in general joining in with its more extended moments. Elsewhere, the “snap” and “bite” of the rhythms was a joy.

The opening of the third movement “Introduction” with its bleak and unremitting atmosphere was promising – strings and winds in tandem advanced the sobriety of it all, bringing out an almost Sibelius-like feeling of isolation to the textures. The strings pursued a “wandering” course underscored by the brass and counterpointed by the horns, and with the oboe and flute doggedly “lifting” the mood in places. The brass seemed warmer and more heroic when first entering, but their aspect quickly darkened in accord with the strings, the anguished chordings from both heightening the unease which the flute sought to console. At this point I wanted more, but for whatever reason the composer had decreed “enough”, and before we knew where we were, the finale was upon us and the clouds had dispersed …..

Though the composer might have given this marvellous finale more to react to in situ, the energising warmth and freshness of the movement’s opening textures set the tone for what followed, impulses which seemed like a symbolic renewal of confidence following a dark night of the soul. Lilburn had already in words enjoined his fellow-composers to engage in what he called “a search for tradition” relating to the necessity of “writing our own music”, in his now-historic 1946 Cambridge Music School lecture written under the same title. Here, now, he practised his own dictum in the composition of this symphony, and to the extent he felt it necessary, whatever critics might say about the result! The work emphasised both challenge and possibility, and the results today spoke for themselves.

The coming-together of these things in this finale was a heady experience – moments in which the big ringing brass theme soared out gloriously, and the orchestra in other places seemed to pick up its skirts and dance were made the more memorable by a final peroration begun by stratospheric strings, and chiselled out of the texture by resounding brass and rolling timpani in glorious C Major! It had the effect of consuming everything at the concert’s conclusion in swathes of splendour and happiness!

Joyce DiDonato sings Berlioz with the NZSO and Gemma New – photo credit Phoebe Tuxford

Joyce DiDonato sings Berlioz with the NZSO and Gemma New – photo credit Phoebe Tuxford

Wellington Youth Orchestra – Conductor Mark Carter congratulates WYO leader Alan Kao at the conclusion of the “Fanfare and Fantasy” concert on Saturday May 3rd, 2025

Wellington Youth Orchestra – Conductor Mark Carter congratulates WYO leader Alan Kao at the conclusion of the “Fanfare and Fantasy” concert on Saturday May 3rd, 2025

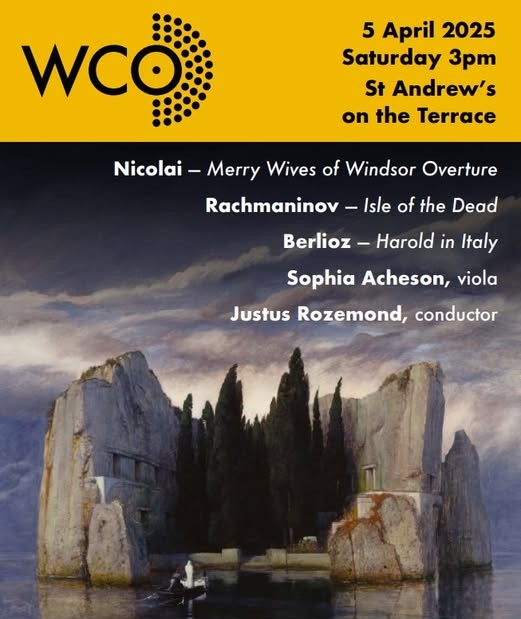

Sophia Acheson, Viola

Sophia Acheson, Viola