WHERE FAIRBURN WALKED

– an exploration of New Zealand Piano Music

Jian Liu (piano)

Rattle RAT – D149 2024 (3 CD set)

In 1987 Kiwi songwriter Ross Mullins wrote a song “Where Fairburn Walked” for an album “Passing Shots”, a song subsequently taken up by singer Caitlin Smith in her 2004 album “Aurere”. Various commentators whose opinions I’ve read have since expressed regret that the song never quite achieved what was deemed “classic status”, though the appearance of its title on a new set of recordings on the Rattle label suggests that It hasn’t entirely been forgotten – in fact I was able to ”connect the dots” in making the discovery that the Steve Garden who currently runs Rattle Records was also the producer of Ross Mullins’ “Passing Shots” album on which the “Fairburn” song itself first appeared.

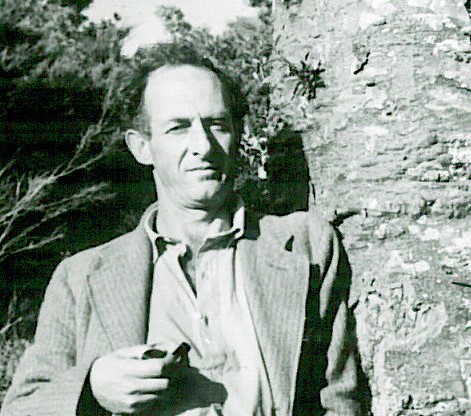

The “Fairburn” of the song is of course poet A.R.D. Fairburn (1904-57), who, at the time of his premature death was considered one of the country’s most important poets – his work has since survived a something of a post-mortem dip in status and regard, with his contribution continuing to undergo a revitalised appraisal. So, when I first saw this new Rattle compilation of twentieth (and twenty-first) century New Zealand piano music bearing the title “Where Fairburn walked” my first thoughts were of some of the poet’s laconic verses from “Walking on my Feet” (Fairburn was an inveterate walker for practically all of his life) –

I know where I’m going

where I’ll lie down

nice quiet place

Long way from town

long way to go

I’ll sleep all alone

fingers round the earth

earth round the bone…

The simple directness of such writing is disarming, though not characteristic, as readers of Fairburn’s other poetry will know – but the willingness to engage with the isolation and earthiness of the land heightens the appropriateness of the new recording’s use of the poet’s name, as it does with much of the music we hear.

A.R.D (Rex) Fairburn

Rather more poetically evocative in terms of imagery and feeling (and according more readily with some of the music found on these recordings) are these lines from a later poem “Estuary” –

The wind has died, no motion now

in the summer’s sleepy breath. Silver the sea-grass

the shells and the driftwood,

fixed in the moon’s vast crystal.

The lynch-pin of this latest undertaking has been pianist Dr. Jian Liu who’s currently both the Head of Piano Studies at Te Kōkī New Zealand School of Music, Victoria University of Wellington, and the Acting Head of School at the NZSM, and is widely celebrated both as a performer and music educator. The recording was in fact produced by Dr.Liu in conjunction with sound engineer Graham Kennedy at the New Zealand School of Music’s Adam Concert Room, with help from the New Zealand Music Trust and Rattle Records. Funding for the project came from Creative New Zealand in conjunction with Victoria University of Wellington and SOUNZ Centre for New Zealand Music, and from the New Zealand Music Trust itself. The recordings complement an earlier undertaking involving the publication in China of two volumes containing these same piano works by the Shanghai Music Publishing House, the largest classical music publisher in Asia.

I did express some surprise to Jian Liu at the omission of any of Douglas Lilburn’s piano music from the set – however, because of difficulties in securing copyright from the Lilburn Estate to publish any of the composer’s pieces in China, it was decided to maintain the accord between the publication of the music and these recordings. Of course Lilburn’s spirit is still a “presence” far beyond the single actual reference to him found in Jenny McLeod’s Tone Clock Piece X – “for Douglas on his 80th birthday”. It’s Interesting that Fairburn himself was well aware of Lilburn as a composer, and in fact they corresponded regarding the possibility of Lilburn setting some of Fairburn’s poetry, with the composer suggesting that the “shorter, simpler poems” (such as the aforementioned “Walking on my Feet”) would be best for such a purpose (Denys Trussell “Fairburn” Auckland University Press 1984 Pg.212) – alas that it was an idea that never bore fruit.

Still, these might-have-been conjectures have their own separate life; and Lilburn’s piano music has certainly received its due on disc already through the stellar efforts of interpreters like Margaret Nielsen, Dan Poynton and Michael Houstoun over the years. It’s entirely appropriate that this new set of recordings should be a world unto itself, one in which the compelling uniqueness of the music’s character is honed by the incredibly-focused commitment towards and identification with the music on the part of Jian Liu. And completing the picture is the brilliance, clarity and atmosphere of sound engineer Graham Kennedy’s recording. The three discs together constitute an overall programme whose structure sustains listening interest through both consistency and contrast. Jian Liu himself indicates in the booklet notes that each disc represents “increasing levels of technical difficulty and musical complexity”, providing new and interesting repertoire choices for pianists in different spheres of activity.

Disc One reflects the possibilities for pianists wishing to begin such a journey – and there ‘s a kind of chronology present as well in the process which adds to the flavour of things with names like Warwick Braithwaite, Thomas Haig, Gordon McBeth, Harry Hiscocks, Ernest Jenner, and Paul Schramm, all of whom were born in the nineteenth century. There’s a definite period charm about Warwick Braithwaite’s Fragment, Gordon McBeth’s An Idyll, Harry Hiscocks’ Nocturne, and Ernest Jenner’s Foxglove Bells – and both Thomas Haigh’s deliciously glutinous-sounding Rotorua (Boiling Mud Pools) with its accompanying touches of gothic atmosphere, and Paul Schramm’s What a Silly Joke with its knockabout comedy routine are all evocatively presented by Liu’s ever-prevailing sense of time, place and character in the music.

On the same disc one finds contemporary composers exploring these same charming, fragrant, atmospheric, and pictorial evocations – though there’s insufficient space to comment on every individual piece one still responds to Ronald Tremain’s artlessly attractive Sleigh Ride, and Claire Cowan’s more exploratory Paper Dragonfly, and with extension of the rich variety of keyboard textures provided by David Hamilton’s Clouds over Aoraki and Gillian Whitehead’s Outlines Through Rising Mists. Gareth Farr’s Love Songs and Anthony Ritchie’s Caroline Bay Suite set simple but satisfying rhythmic challenges of ostinato and syncopation.

The remainder of pieces on the disc take the player to more demanding levels of achievement both technically and interpretatively with Jenny McLeod’s Mysterious Whirly Square Dance providing a stimulating test for any beginning player, and Paul Schramm’s already-mentioned What a Silly Joke even more so. Gillian Whitehead’s Lullaby for Matthew and Craig Utting’s Covenant have more reachable notes but inhabit worlds which require an advanced synthesis of hands head and heart. And so to John Elmsly’s Six Little Preludes which conclude the first disc and which in Jian Liu’s hands definitely represents a kind of technical and aesthetic gateway through which a player needs to pass to tackle the demands of the “next level” of keyboard accomplishment.

Straight away one senses a more elevated world of expression with the beginning of Disc Two, and one to which the pianist instantly responds, firstly with Kenneth Young’s Elusive Dream, a series of spontaneously-wrought roulades becoming increasingly interactive as their explorations flirt with both expectation and illusion – a kind of “growing-up” metaphor, an awakening to a new reality. Liu adroitly enables David Farquar’s Three Inventions to playfully lock horns with one another before coming to a kind of “rubbed-off-edges” terms with themselves, while Ross Harris’s utterly charming Nga Manu delineates by numbers the birth processes of birds from incubation, through hatching and feeding and pushing out fledglings, including a somewhat pitiful “runt of the litter”. Leonie Holmes’s Nocturne comes with a poem describing the flight of a moth, the sounds, Liu perfectly realising Holmes’s fine detailing expressing the creature’s “Midnight Empress” status and her “unchallenged” sweep into and through her “hushed domain”. And just as majestic in a different, “other time and place” manner is Michael Williams’s Arteria Meridionali, whose ritualistic, almost Respighi-like gestures seem to evoke something of their European origins.

It was simply my way of thinking about things, but Anthony Ritchie’s grandly-conceived Olveston Suite, a tribute to an historic Dunedin stately home, seems to mark the end of the set’s “coming of age” evocations, the “grand gesture-like” sounds nostalgically reawakening my youthful impressions of such places with their faded glories and echoes of old times. Everything here seemed like a newly-minted dream with lots of rumbustion (The Kitchen and Scullery – as well as, surprisingly, the Billiard Room!), proper old-world etiquette (the Dining Room) and some genteel tranquility (the Writing Room), all part of the fairy-tale-like fantasy of a lost age.

After this, I felt the remaining works on the disc, Jenny McLeod’s Four Tone Clock pieces and Anthony Ritchie’s selection of PIano Preludes, possessed a gravitas which lifted them away from the other pieces, more akin to the collection of works on Disc Three. All of the pieces had that depth of content, either focused or discursive, which required the kind of responses to technical difficulty and/or musical complexity as outlined by Jian Liu in his introduction to the set.

McLeod’s Tone Clock pieces were inspired by Dutch composer Peter Schat’s theories regarding equal-temperament tonal and chromatic approaches, expanding Schat’s basic idea to incorporate what she called a “Grand Unified Theory” far beyond the idea’s original source. Liu plays four of McLeod’s twenty-four pieces, two of which are each dedicated to previous composer-colleagues of Mcleod – Douglas Lilburn and David Farquhar – both of whom had preceded her as Professors of Music Studies at Victoria University. I imagined I could “hear” certain characteristics of each of the older composers in the pieces McLeod had inscribed to them.

While more conventionally named as “Preludes”, Anthony Ritchie’s survey for solo piano encompasses the accepted spectrum of all twenty-four keys from the chromatic scale. Jian Liu recorded five of these for this recording, covering a wide range of differing “character” pieces, influenced to some extent by other composers’ efforts in this form but remaining true to the composer’s own “sound and musical expression”. Each has a particular distinctive character which Liu brings out with splendid-sounding surety – I particularly enjoyed the contrasts in his playing of No. 15, with its agitated, excitingly “dangerous-sounding” figurations vying with bell-like treble sounds, dismissed mockingly and derisively, when compared with No. 24 (subtitled “For my Mother”), a time-aged memory of mother and child at the keyboard perhaps? – something at first charming and nostalgic, though at the end, sounding a strangely forlorn note…..

True to Jian Liu’s previously-quoted overview, the two previous pieces and those occupying Disc Three all seemed ineluctably “ingrained” in terms of conveying a character, environment, situation, emotion or any other such viewpoint relating to this part of the world with requisite skill and conviction. Two of the third disc’s pieces were by composers whose music was appearing for the first time in this set – interestingly one was the oldest in the group (Edwin Carr 1928-2003) and the other was the youngest (Selina Fisher (b.1993) – beside which we heard further works by David Hamilton, John Psathas, Gareth Farr, Gillian Whitehead, Claire Cowan and John Elmsly.

Whether it was the juxtaposition of youth and age, or the “newness” of the two composers’ music on this disc, I found myself unexpectedly, but more resoundingly, drawn to both Edwin Carr’s and Salina Fisher’s very different sounding works. Carr composed prolifically in most forms, including a number of works for solo piano, among them this attractively-varied set of four sharply-characterised pieces requiring from the player, by turns, both a lyrical touch and brilliant virtuosity. By contrast Selina Fisher’s world is more readily ambient and impressionistic, though capable of sharply-etched incident and irruption, however micro-cosmic. Both of these pieces would certainly encourage me to seek out further explorations and expressions of the world of sound, light and ambience through which we all move and deign to share with others. It‘s a kind of overall unifying quality which all of the pieces on these three discs so brilliantly and evocatively presented here by Jian Liu have a share in defining and characterising as our very own distinctive living-space.