Wellington City Orchestra presents:

Wellington City Orchestra presents:

MOZART – Overture “Cosi fan tutte” K.588

MOZART – Concerto for Flute and Harp in C Major K.299

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV – Symphony No. 3 in C Major Op.32

Karen Batten (flute)

Michelle Velvin (harp)

Wellington City Orchestra

Andrew Atkins (conductor)

St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Wellington

Sunday, 22nd September. 2024

To the title of this review I was tempted to add the word “enterprising”, in referring to the inclusion in Wellington City Orchestra’s programme of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s little-known and until recently rarely locally-performed Third Symphony (“You mean there are two others?” someone quipped to me at the concert during the interval!). I was therefore amazed when a search of on-line recording catalogues revealed no less than five recordings featuring the work, and in most cases as part of a set of all three symphonies – until recently only “Antar”, the Second Symphony, had any kind of recorded history. So, while not exactly a neglected and forgotten work per se, the Third Symphony had been something of a rarity in Aotearoa’s concert halls up to the present, and certainly deserved its airing on this occasion, thanks to the advocacy of conductor Andrew Atkins.

The concert’s other two works needed no such special pleading, though of Mozart’s instrumental concertos perhaps K.299, the Flute and Harp Concerto has a special place because of its attractive instrumental combination. It obviously needs a harp, an instrument less prolific than others in the composer’s “concerti canon”, but somehow its “specialness” seems an extra drawcard, adding to the beauty of the sounds generated by both the instrumental combination and the composer’s music.

As for the concert’s opening item, another work by Mozart, the Overture to “Cosi fan tutte” perhaps is the least “known” in concert-hall performance of the composer’s “big four” operatic overtures (it was the one of the four that didn’t make the “cut” in a recent Classic FM list of “Ten greatest Opera Overtures”) though it’s still a work of immense distinction, and one that has its own challenges. I liked conductor Andrew Atkins’ overall projection of the music, the introductory fanfare chords snappy and alert and the flowing oboe solo characterfully shaped (both gestures are repeated), before the whole orchestra stated the opera’s “signature phrase” emphatically sung by the male principals at a later stage in the opera – “Co-si-fan-tu-tte!” – and the mischievous allegro theme skips in, alternating with emphatic syncopated chordings and repeated perky phrases from the various solo woodwinds, which continue throughout the overture until the return of the “signature phrase” and a coda whose ending signals the “opera proper” to begin. While keeping the trajectories alive and bubbling, Atkins still gave the strings plenty of space in which to articulate their phrases with those tricky, syncopated opening entries, something that was less troublesome for the wind-players, whose chattering solos invariably began ON the beat! It all set the ambiences tingling for the delightful Flute and Harp concerto to follow.

A bright, freshly-voiced opening paved the way for the soloists’ unison entry, scintillations of colour and energy whose interplay gave as much active stimulation as more passive enjoyment, thanks to both the composer’s inexhaustible invention and his soloists’ spontaneous-sounding relishing of so many details, whether in individual exchange, or in tandem with the orchestra – the sense of delight at times over-rode my duties as a reviewer, so that I had to often break the spell and remember to write a comment regarding this and that felicity! I particularly enjoyed the first-movement cadenza which began slowly an almost suggestively and teasingly wrought between the players – Karen Batten’s flute was well-nigh vocal at times with her turns of phrase, and Michelle Velvin’s harp sparkled and glistened in response, her concluding flourish before the orchestra re-entered a wonderful irruption of tongue-in-cheek temperament!

Conductor Atkins got a most charmingly poised and gracious opening tutti from the players at the slow movement’s beginning, to which the soloists brought episode after episode of enchantment, after which the finale danced in, the sprightly opening getting even livelier as the figurations took on even greater excitement! The harp took the lead, showing the flute the way, with both soloists then relishing Mozart’s unfailingly ear-catching invention in their exchanges. A lovely “where have we got to?” shared cadenza concluded with another spectacular harp flourish and the final tutti an “all-in” affair with the soloists at the forefront of the “payoff” chords – splendid! I wasn’t expecting to enjoy it so much!

An interval allowed time and space for the resplendent harp to be spirited over to one side, and for musicians and audience alike to prepare for the second half, and the eagerly-anticipated Rimsky-Korsakov Symphony. The work got off to an atmospheric start with horns calling across the orchestra soundscape to firstly winds and then strings, everything lovely and rhapsodic, with Atkins then encouraging plenty of momentum and muscle for a well-managed accelerando into the allegro – this was classic “Russian festival” stuff with the reprise of the big, prancing tune especially invigorating. Some beautiful wind-playing then introduced a second subject, begun by the clarinet and forwarded by the oboe and strings, then a solo violin and flute, all poignantly sounded before Atkins danced everybody into the development section, with firstly the strings and then the winds having a lot of fun with all kind of variants of both of the themes we’d so far heard. The brass and timpani then called things together resplendently for a massive return of the allegro’s main tune – stirring stuff, here! – after which the winds, led by the clarinet, brought back (for our pleasure) the lovely second subject, commented on by various other winds and the solo violin. And then, Instead of the “great peroration” method of finishing a movement, conductor and players wound it all down quietly and poetically, concluding with gentle, po-faced pizzicato-and-wind notes.

Something of a challenge was posed by the composer’s 5/4 rhythms in the quixotic scherzo (marked “vivo”) which followed – unlike the stately step-wise processional of Tchaikovsky’s Allegro con grazia 5/4 movement in his “Pathetique” Symphony, these rhythms conjured up a positively mercurial momentum, whose trajectories I thought the players did a fantastic job of maintaining. I did wonder while listening whether it was out of mischievous intent towards or something akin to dislike of orchestral players that led Rimsky-Korsakov to set them such a task, but on this occasion, to the WCO’s credit (and their conductor’s), the players kept those handfuls of semiquavers simmering for our delight – and at least the Trio’s contrastingly languorous melody gave all and sundry a bit of a rhythmic breather!

I thought the Andante movement lovely, with horns and winds creating a gorgeous introduction here, from which the strings elaborated the melody, repeating its opening in different keys (a “soaring aloft” set of phrases made a particularly fetching impression) – the theme continued to draw in responses from all sides, alternating more excitable moments with the previous “soaring” mode – though largely monothematic, the mood had an enchantment of its own which held one’s interest to the point where the pulse quickened more purposefully and drove the sounds into a celebratory finale. Though the opening martial melody was perhaps over-worked, it all certainly demonstrated the composer’s skill as an orchestrator, and managed to weave in fragments of counter-themes by way of contrast, with playing sufficiently committed and colourful from all sections of the band keeping us mightily entertained right to the end. In all, I felt it was definitely worth a listen, and may well even be tempted into further symphonic investigations, having been reminded earlier that “there are two others!” So, definite kudos to Andrew Atkins, his soloists and supporting players for an absorbing and rewarding afternoon’s listening!

Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu

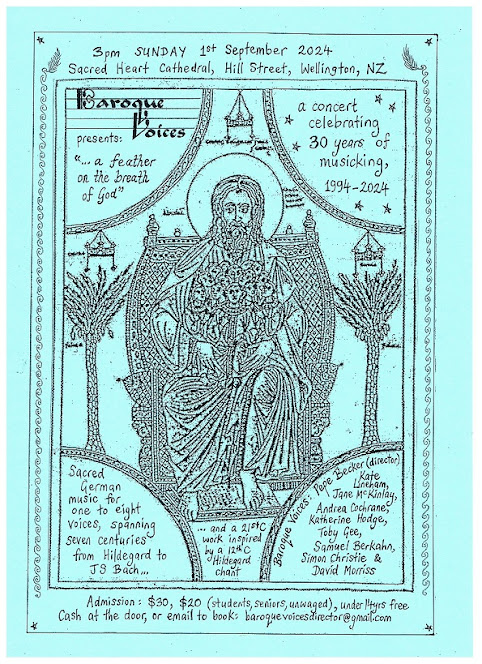

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach –

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach – Baroque Voices 2024

Baroque Voices 2024