Shostakovich and Britten

Shostakovich and Britten

PARTY FAITHFUL

BRITTEN – ‘Cello Symphony Op.68

SHOSTAKOVICH – Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major Op. 20 “The First of May”*

Lev Sivkov (‘cello)

Marc Taddei (conductor)

*Orpheus Choir of Wellington(Brent Stewart, director)

Orchestra Wellington

Michael Fowler Centre, Wellington

Saturday, 26th July 2025

Review for “Middle C” by Peter Mechen

What an occasion! – TWO New Zealand premieres, Britten and Shostakovich, in one evening! While perhaps not unique in this country’s concert-giving history, such an event’s “blue-moon” aspect provoked all kinds of responses from the capital’s music fraternity, with the music’s unfamiliarity seeming at once a drawcard with its own kind of excitement and sense of discovery, and something of a risk! – the relatively unknown administered here in what might have seemed to some like over-sized doses! With characteristic adventurousness, Orchestra Wellington and the Orpheus Choir of Wellington plunged into the fray, and emerged triumphant on all fronts, the audience’s enthusiastic response at the conclusion of each of the concert’s halves unequivocally and unstintingly great-hearted, more than making up for the marginally thinner attendance compared with the numbers present at the season’s first two concerts.

How was this near-miracle of approbation brought off so heart-warmingly? – several reasons; firstly by the charismatic cellist Lev Sivkov’s “owning” of the somewhat elliptical solo part of Benjamin Britten’s formidable ‘Cello Symphony; secondly, via conductor Marc Taddei’s remarkable mastery of the scores and control of his orchestral and choral forces; and lastly through the astonishing results of the intrepid musicians’ meticulous efforts in regard to each of the works’ completely different demands! So it was that Marc Taddei would have felt more than justifiably vindicated in his pre-concert enthusiasm regarding the “adventure” of this undertaking.

First up was one of the more enigmatic works by Benjamin Britten, his singularly-titled “Cello Symphony” begging the question regarding the piece’s actual genre, having an instrumental soloist in a work styled as a “symphony”, and bringing together what might normally be regarded as differently-constituted musical narratives. It wasn’t an entirely unknown format, with previous works by various composers entitled “Sinfonia Concertante”, and with composers (like Berlioz in his work for viola and orchestra “Harold in Italy”) having produced “symphonies” with solo instrumental parts.

Such works had in the past produced problems of thwarted expectation on the part of musicians (the most well-known being the legendary violinist Paganini’s dismissal of Berlioz’s aforementioned work, and which the former never played). Britten’s dedicatee was the renowned cellist Mstislav Rostropovich (for whom he had already composed several pieces), and who had probably expected a brilliant instrumental concerto showpiece compared with what he actually received. What Britten was writing proved to be a tribute to the ‘cellist’s musicianship as much as to his technical brilliance, as the work casts the soloist as an equal partner with the orchestra in their exchange and development of the work’s themes and juxtapositions and contrasts.

An enjoyable and intriguing aspect of tonight’s performance was the engagingly demonstrative playing of the cellist, Lev Sivkov, whose gestures had an expressiveness which choreographed the musical line and strengthened the interplay between soloist and orchestra. Though the cello’s opening double-stopped chords were brusque compared to the orchestra’s darkly-conceived lines, they had a pliability that suggested dialogue more than opposition, even when the soloist’s increasing energies brought “spiky” wind chordings and “snappy” brass notes, as subsequent lyrical exchanges between the cello and clarinet and flute phrases more readily suggested, and which the oboe and brass softly continued. Particularly memorable was a touching sequence of interplay between pizzicato strings and cello outpourings, even if the latter’s somewhat anxious two-note phrases against the strings pizzicato began suggesting more darkness than radiance and conflict afoot, brought into increasing prominence by the timpani’s repeated patternings, and the winds and heavy brasses exchanging chords. But a desire for accord persisted with brass-and-percussion irruptions balanced by beautifully poignant-sounding wind-harmonies – almost fairy-tale sounds – as if simultaneously-wrought “threads” were constantly trying to “dance around” each other, with the cello playing a kind of “fulcrum” role, keeping determinedly businesslike amid the claustrophobia of heavy percussion irruptions, brass “pedal-notes” and skitterish wind passages. We sensed relief with the soloist’s response to it all – poised pizzicato chordings over resignedly rumbling lower instruments, while the winds played a Mahlerian “dying fall” theme – a soft gong-stroke and a few pizzicato notes later this absorbing movement came to an enigmatic close.

What a marvellously nocturnal scherzo we got next! – the cello quicksilver, playful and even furtive, and straightaway alerting the muted brasses! The soloist’s dancings were answered throughout with either gruff single notes or quixotic, melismatic figures haunted by the brasses’ echoings. Constant movement and exchange became increasingly frantic, halted at the end by the cello’s animalistic whimperings and a dismissive grunt from the brass – all brilliantly-conceived, and here superbly-realised! By contrast, the Adagio’s solid, granite-like tones brought a solemn march, the cello’s solemn, step-wise theme replete with massive timpani ramparts and mournful keenings from winds and an evocatively responding horn solo – and what beauties the soloist with supporting horn, strings and gentle percussion gave us here! The rest of the movement returned to the march-like opening, the brass splendidly building the music’s progress towards a grim magnificence while the cello increasingly rhapsodises in defiance, and eventually breaking into a cadenza, one whose progress soloist Lev Sivkov mesmerically “defined” for us with his rapt, seemingly improvised gesturings throughout

Without a break, the music transmorgrified into the finale, the solo trumpet sounding a kind of “liberation” as the cello seemed to walk from the darkness and into the light afforded by the concluding Passacaglia’s six variations. I loved the winds’ dancing sequences, the cello’s mad scamperings pursued by winds and percussion, and the intensely Mahlerian rhapsodic fervour of the cello’s musings immediately before the great surge of long-awaited optimism given to us by the whole orchestra’s tsunami-like concluding response to the soloist’s heartfelt efforts!

If I’ve dwelt overmuch on the music’s detailings at the expense of its actual delivery, here, it’s because the performance was a further (and remarkable) step towards my own appreciation of what I found an initially challenging listen! – I hope these reams of self-indulgence have some point for the reader, especially any finding themselves going through the same process of determined discovery!

Shostakovich’s Third Symphony, another work new to me, was a different kind of journey, one no less fascinating, but somewhat less “layered” than the Britten work, though it brought its own set of distinctions to the concert, One of these was its composer’s own remark, now forever associated with the work – “It would be interesting to write a symphony where not a single theme would be repeated”. one that he strove to fulfil with this remarkably vernal, pulsatingly “in-your-face” music.

What made the performance more than worthwhile was the up-front orchestral playing, and the “joyful and triumphant” tones of the evening’s “rent-a-socialist” ensembled voices, the Orpheus Choir. Printing the English words in the programme was tongue-in-cheek enough – a real blessing was being given these indecipherable words as sterling statements unimpeded by on-stage visual translations! – heed was taken of conductor Vasily Petrenko’s words in the programme notes concerning the “banal, amateur” poetry – and the supreme irony of the presentation came with the performance’s full-blooded commitment to the cause (of the music, of course!). Maybe some day we’ll get to hear some of those later Shostakovich symphonies from this orchestra as well! (imagine the subscription numbers generated by the thought of THAT series!)

For now, we had our ears bent in somewhat different directions as Marc Taddei and his seemingly tireless musicians took to Shostakovich’s most irreverent piece of symphonic writing to date. Despite its beautiful opening for two clarinets (superbly delivered) the work soon accelerated into a veritable ferment of action. dissonant passages crowding one another as the trajectories rang the changes from grim martial rhythms to maniacal scamperings, culminating in grotesque “horror-chordings” and continued reckless headlong careerings, whose frenzied momentums were lessened by a side-drum’s call to attention, a solo clarinet succeeding in quelling the energies of the flight, and bringing an uneasy calm to the soundscape after further horror chordings reacquainted acquainted us with the obstacles still to be surmounted.

From here, we were given a few stress-free moments of relative tranquility from solo violin and eerily spectral winds, the latter gradually shrugging off their ghoulish aspect in search of some much needed pastoral charm, gladly welcomed by the strings, their warmth persuading other elements that a salvation of sorts might be imminent –everybody dug more deeply, pulling from out of the depths of texture sonorities and impulses which seemed to gradually ignite the whole orchestra! A fresh burst of momentum brought in compulsions of rhythm, particularly Russian in flavour, whose energies pushed the music onto a kind of plateau of heroic expression, underlined by a great percussive onslaught –something momentous was being enacted, leaving us awaiting the arrival of some great endpoint, a kind of magnificence whose presence we sensed but whose entry was still being prepared. Then, with a great cymbal crash, the choir suddenly stood up, electrifying us all!

A brief orchestral introduction and the voices burst out, whole-heartedly, lustily – oceanic waves of sound punctuated by percussive irruptions, peaking and breaking over the edges and washing over their listeners. We knew and did not know of what they sang – it mattered less than their fervour and spirit and sense of joy! And at the conclusion, with the musicians having given their all, we relished their achievement amidst our shared relief and exhilaration!

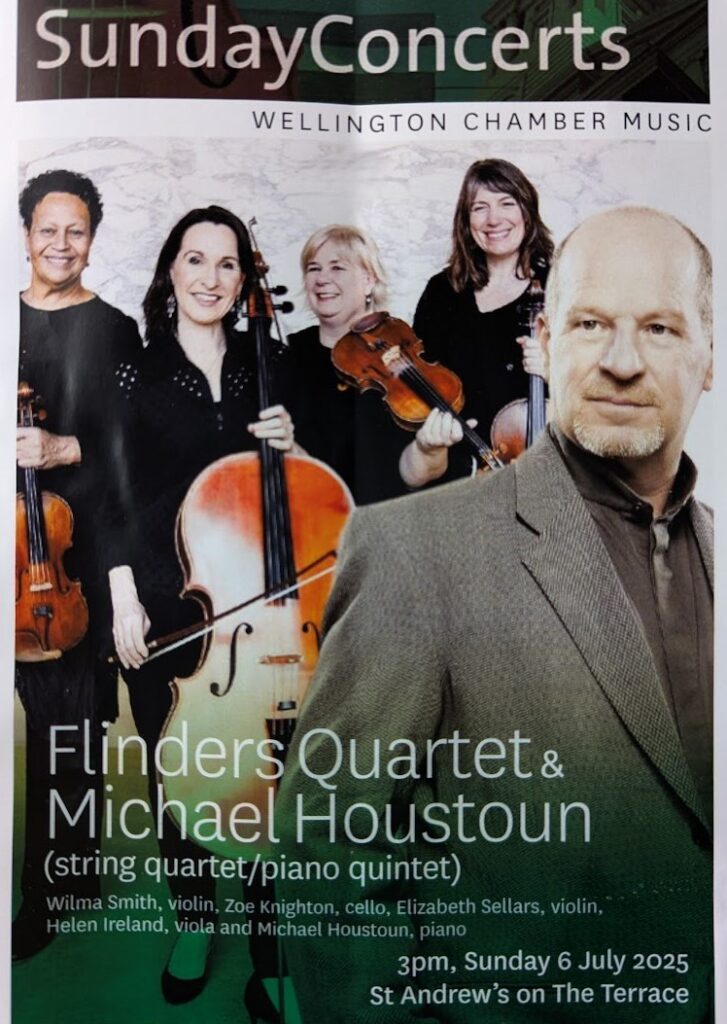

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich Orchestra Wellington with Marc Taddei rehearsing Shostakovich

Orchestra Wellington with Marc Taddei rehearsing Shostakovich