CANTORIS – A Night at the Opera

Cantoris Choir

Soloists: Barbara Paterson (soprano), William McElwee (baritone)

Music Director: Ingrid Schoenfeld

Piano: Heather Easting

Ruggero LEONCAVALLO – Bell Chorus from I Pagliacci

Giuseppe VERDI – Anvil Chorus from Il Trovatore

George Frideric HANDEL – Chorus of Enchanted Islanders from Alcina

Giacomo PUCCINI – Humming Chorus from Madama Butterfly

Georges BIZET – Habanera, with Chorus from Carmen

Toreador Song, with Chorus, from Carmen

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART – “Heil sei euch Geweihten” from The

Magic Flute

Christoph Willibald GLUCK – “Quel est l’audacieux” from Orphée et

Eurydice

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART – Voyagers’ Chorus from Idomeneo

George Frideric HANDEL – “How Strange their Ends” from Theodora

Henry PURCELL – Dido’s Lament and “With Drooping Wings”

from Dido and Aeneas

Giuseppe VERDI – Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves from Nabucco

Brindisi (Drinking Song and Chorus) from La

Traviata

Carl ORFF – Chorus “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana

St.Peter’s-on-Willis-Street, Te Aro, Wellington

Saturday, 10th May 2025

What a splendid blockbuster of a way for a choir to begin a season! – and with so many wonderful moments that have actually transcended their “high art” origins and are now “in the culture!” – and none the worse for it! So often certain pieces of music are deemed well-known to the point of cliché, and are therefore passed over, in favour of something more “interesting”. But! – as I fondly remember from my own formative years, it was often one of these very pieces, which would have been regarded by others as “hackneyed”, whose first hearing hit me like a ton of bricks, and to the extent that life was never the same again afterwards!

At school, in the Fourth Form, I had the good fortune to have a teacher who was himself an opera fan – so he would play to us pieces from a recording (of which I now have a prized copy!) of “Opera Choruses”, ALL of which I simply fell in love with on first hearing! – it was partly the way he introduced them to his class of rough-diamond, mostly rugby-playing and pop-music-loving boys who probably didn’t at that stage know Wagner from a Weet-Bix packet, but who listened, spell-bound as he described scenarios to go with the choruses, such as how a rich man, sitting miserably in his house surrounded by his wealth, suddenly heard a crowd of pilgrims passing in the street outside, singing “Alleluiah” at the tops of their voices as they went by the man’s window – and how the man was galvanised by what he heard, and, leaving his house and possessions behind, rushed down the road to join them! – and then, of course, our teacher played us the actual recording of the chorus, and we were “there”, listening to these voices, and imagining how we would have been filled with wonderment at the sounds and jumped up at the end to follow the voices ourselves. This particular chorus (the Pilgrims’ Chorus from Wagner’s “Tannhauser”) wasn’t among Cantoris’s presentations, but the others had an effect this same evening that vividly brought back that memory to me, of my sensibilities being unexpectedly “ignited” by something whose appeal was direct and enduring!

What was especially wonderful at the Cantoris concert was how the choir, with the barest minimum of forces (no orchestra, and no elaborate stage or theatrical trappings with which to fill out the scenarios), was able to generate from their music-making something of this excitement of both discovery and rediscovery amongst their audience. For this they could thank in addition an inspirational music director, Ingrid Schoenfeld, a brilliant pianist, Heather Easting, and two solo singers, soprano Barbara Paterson and baritone William McElwee who threw themselves wholeheartedly into their characterisations of various roles associated with certain of the choruses. Audience reaction to each and every one of the items (even those whose unexpectedly abrupt endings might have taken by surprise people who were just beginning to “groove along” with things – however, opera, as any enthusiast knows, thrives on the unexpected!) was enthusiastic and wholehearted, and the programming with its variety of settings, situations and characterisations meant that one’s interest never flagged.

Within this variety were placed a number of sure-fire favourites with tunes that everybody seems to have heard somewhere or other, those “part of the soundscape” melodies which seem to have always been there – such were two of the Verdi choruses (the “Anvil” Chorus from “Il Trovatore”, and the “Hebrew Slaves” Chorus from “Nabucco”), Bizet’s perennial favourite “Habanera” (solo-and-chorus) from “Carmen”, and the more recent “classic” from Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana”, that’s made up for lost time on various television advertisements, “O Fortuna!” Each one had plenty of impact of satisfyingly varying kinds, even if in the “Il Trovatore” excerpt the anvils sounded more “Janissary-like” than whole and ringing, and the gypsy men fudged their first “All’opra! all’opra!”, probably through thinking too much about the gypsy women! Such a distraction wasn’t a problem with Barbara Paterson’s alluringly three-dimensional portrayal of Carmen in the “Habanera” (the singer using the church’s central aisle to palpable dramatic effect!) – and though baritone William McElwee couldn’t quite match her range of vocal colour and impulse, his confident “presence” as Escamillo in the Toreador’s Song, did ample justice to the bullfighter’s swaggering character, both singers backed to the hilt by the choir’s support and the unfailingly buoyant trajectories of Heather Easting’s accompaniments!

On a different emotional plane were two other solo-and-chorus presentations which resounded afterwards in the memory, firstly Gluck’s chilling “Quel est L’Audacieux” from Orphée et Eurydice, featuring the choir of Furies guarding the Underworld with tones fearsome and implaccable – and the baritone a tremulous but staunch and persistent supplicant, driven desperately by his love for Eurydice to bring her back from the land of the Dead – the atmosphere generated by the confrontation was properly chilling, with the choir’s tones dark and malevolent before being moved to pity by McElwee’s plaintive pleas – a memorable evocation. Though not cheek-by jowl on the programme, fortunately, we still couldn’t help but register the contrasts in almost every way between the Gluck scenario and Henry Purcell’s famous “Dido’s Lament”, one of opera’s most heart-rending scenes, and given all the space needed for both impulse and stillness to work a powerful spell – Paterson’s singing was beautifully-poised, purer of tone on her second-time-round ascent at “reMEMBER ME” and thoroughly affecting altogether, as was the choir’s following “With Drooping Wings” chorus, its sombre tones and heartbeat-like phrasings seeming to put all of us closer to our tenuous grasp upon life than we might have otherwise wanted.

I don’t intend to scroll through the entire programme in this review, but would like to register some more specific enjoyments, such as the opening “Bell Chorus” from Leoncavallo’s “I Pagliacci”, which gave us plenty of bright, vibrant bell-sounds and ear-catching dynamic variation. Another was the chorus from Handel’s “Alcina”, well-remembered from an enterprising production I attended some years ago at Day’s’ Bay Opera, and bringing back some lovely evocations of that time. In fact the programme as such had a number of lesser-known choruses from works such as from another Handel work, an oratorio “Theodora” (again, adventurously performed, and heard by me, at Day’s Bay, incidentally, as an opera!). Any memory of the work had by this time gone, so it seemed like a new and wondrous experience for me, a solemn, processional-like journey sustained partly by long-held notes, and at other times closely-worked phrases that seemed to gestate from these same lines like a plant coming into flower, the whole suiting the passage of thought and expression of wonderment – for me, a delightful rediscovery!.

Another came from Mozart, this time his “Idomeneo” (one which gave Barbara Paterson another chance to shine as Elettra, one of the characters in the opera’s story, here expressing hopes with some trepidation for a calm voyage to her homeland with the person she loves) – a kind of Mozartean “Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage” work, here given with flowing, undulating tones from the choir, taking the treacherous upward leap towards the end in their stride!

Comments in general? These are mere opinions and can be regarded as such – but I have to confess to wishing that the trajectories of just a couple of the items had been allowed to flow more easily and dreamily – Puccini’s “Humming Chorus”, for instance, I prefer to hear sounded as if it’s almost “breathed” rather than sung and that we listeners are eavesdropping on something really private and close to the heart! To an extent I thought also that the “Va, pensiero” Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves could also have been taken as if in a dream at the start, making the “outburst” in the middle more of a kind of the captives’ “awakening” a demonstration of despair and grief at their predicament – “O harp, why do you hang so silently?…rekindle the memories in our hearts!”

Enough! – reviewers of concerts should talk about what and how things were done, played and sung, rather than compile wish-lists of such things as “could-have-beens!”! It will be obvious that I got such a lot of pleasure from out of the concert, a good deal of which was reinforced by the enjoyment of those sitting close to me and of other people I talked with afterwards. Congratulations and thanks are due to all concerned for their part in such a warm-hearted enterprise!

Wellington Youth Orchestra – Conductor Mark Carter congratulates WYO leader Alan Kao at the conclusion of the “Fanfare and Fantasy” concert on Saturday May 3rd, 2025

Wellington Youth Orchestra – Conductor Mark Carter congratulates WYO leader Alan Kao at the conclusion of the “Fanfare and Fantasy” concert on Saturday May 3rd, 2025

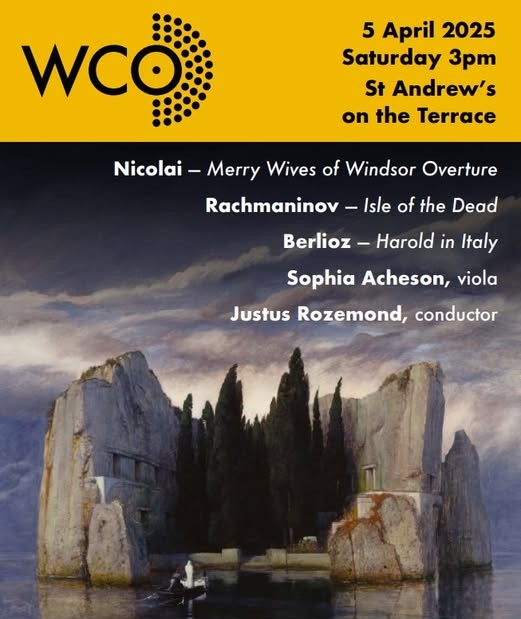

Sophia Acheson, Viola

Sophia Acheson, Viola Helene Pohl and Anna van der Zee (violins), Rolf Gjelsten (‘cello) and Nicholas Hancox (viola) play Shostakovich

Helene Pohl and Anna van der Zee (violins), Rolf Gjelsten (‘cello) and Nicholas Hancox (viola) play Shostakovich Julia Joyce (viola) and the Chamber Pot-pourri Ensemble play Mozart

Julia Joyce (viola) and the Chamber Pot-pourri Ensemble play Mozart Michael Steward and the Tudor Consort at Wellington Cathedral of St.Paul (photo: Cassandra Wang)

Michael Steward and the Tudor Consort at Wellington Cathedral of St.Paul (photo: Cassandra Wang)

The Way Alone – Stephen Baynes

The Way Alone – Stephen Baynes