Wellington Chamber Music presents:

Wellington Chamber Music presents:

Ghost Trio –

TAKEMITSU, BEETHOVEN, DOWNIE and SHOSTAKOVICH

The Ghost Trio – Monique Lapins (violin), Ken Ichinose (‘cello)

Gabriela Glapska (piano)

TAKEMITSU – Between Tides (1993)

BEETHOVEN – Piano Trio in D Major Op.70 No.1 “Ghost”

GLEN DOWNIE – Sonata da chiesa (2024)

SHOSTAKOVICH – Piano Trio No.2 in E Minor Op. 67 No.2

St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Te Aro, Wellington

Sunday 17th August, 2025

Review for “Middle C” by Peter Mechen

“What’s in a name?” could well have been the unspoken phrase hovering about St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace on Sunday afternoon prior to the opening of Wellington Chamber Music’s most recent presentation, whose first item was, as per the written programme supposed to be Beethoven’s D Major Piano Trio Op,70 No.1, better known as the “Ghost”, due to its haunting second movement, ripe for association with famous theatrical “ghosts” such as those that occur in Shakespeare – Hamlet or Macbeth coming most readily to mind. And here, on the performers’ platform was scheduled none other than an eponymously-named trio of musicians to open the concert by “playing their song”. What happened instead, of course, is now history, with the musicians themselves deciding that Beethoven’s somewhat overwhelming string of “ghostly” scenarios could result in tidal waves of resonance that would swamp the gentle undulations of the work by Tōru Takemitsu due to follow.

So, in the minds of listeners who knew the Beethoven, and would have prepared themselves for the exhilaration of that tumultuous opening salvo of energised sounds, the surprise intervention by the Takemitsu work “Between Tides” would have seemed like the proverbial sea-change into something rich and strange! – beginning with such delicacies of sound evoked by lightly astringent piano harmonies, answered by string phrases whose solo lines variously trail into their own silences, or intertwine, Ravel-like in places, briefly touching on their own worlds before returning to the piano’s sway, and awaiting the next version of exchanges.

Throughout, the instruments’ voicings create a world of chameleon-like pursuit of one another, every wave of impulse with its own variant of the same life-force. I was reminded while listening of human breath when still, and of surrendering to impulses not necessarily my own – also of the infinite variety of the experience in terms of what comes with it from one’s imagination – whole worlds of difference, individually with the harmonics or tremolandi played by the strings or the free-ranging spaces between piano notes, contrasted with assertive unison utterances that give further musical food for contemplation. It’s a piece I found throughout to be “in waiting” in general terms, though its tensions occasionally bubble up and almost right over – its ending is satisfying enigmatic, leaving one with the idea of, in TS Eliot’s words, “an eternal action, an eternal patience” ……

Having been suitably dispersed over vast vistas by the action of tides, our sensibilities were then gathered in once again with a vengeance by the promised Beethoven! I was at last allowed the delayed indulgence of pointing out an obvious kind of coincidence, correlation or conjunction with what seemed to me like paradigmatic “ownership” of this music by the ensemble – right from the very first whirlwind ascending phrases there was, I felt, a “this is what we do” feeling of full-blooded identification! The intensities of this work are concentrated, throwing together both heroism and turmoil throughout the opening movement, with as much sprung intensity in the hushed exchanges of the second subject as in the flamboyant opening unison – how “breathing as one” they sounded, here, throughout these contrasting episodes, and how much they relished the concerted singing passages in the development as the more vigorous “horse-and-rider” episodes leading to the recapitulation – such an invigorating journey!

Cello and violin are vibrato-less at the slow movement’s beginning, the piano interspersing with suitably ghostly eloquence, extended by the ‘cello and violin who together voice the feeling of some kind of other-worldly presence, though leading us towards some consolation amid the gloom. The music’s central section begins darkly, the cello leading the way, contrasting agitated and desolate-sounding lines, suggesting personal sorrow, loneliness and frustration in the music’s explorations, the players leaving us with a single repeated enigmatic note over which to ponder at the end.

How resilient the mind that can produce such a finale after so downcast a mood! Here, like with the first movement, was a “tour de force” of ensemble playing, with absolutely brilliant pianism from Gabriela Glapska, and equally stunning dovetailing of their concerted passages from Monique Lapins and Ken Ichinose. The “questioning” aspect of the opening theme led to all kinds of suspensions and adroit manoeuvrings of both the whimsical and helter-skelter variety, leaving us all breathlessly invigorated at the end, and somewhat gob-smacked at both the individual and concerted virtuosity of the players!

Glen Downie’s was a new name for me, as was the work, Sonata da Chiesa, a piece written this year for the Ghost Trio to take on tour. The music takes its name (literally, “Church Sonata”) from baroque times, and was inspired by music written by Vivaldi for the ‘cello. In a programme note Downie talks about the music “breaking away” from its original inspiration (characterised by ruins of “worn material”) and attempting to rebuild anew from the “surviving stone”. A specific inspiration for the piece was a UK building, the Christchurch Priory, originally a Norman building, but containing layers wrought by different eras in the building’s history, a quality Downie intended his piece to replicate as “a uniform expressivity”

In four movements, the piece began with piano arpeggios, and attention-grabbing violin notes, the latter reverting to a sombre exploration of the piano figurations, whose buildup suggests an architectural quality, with a dancing violin astringency supplying outward detail and reaching a climax as the cello supports the structure with an ostinato-like figure.

Beginning with a rushing piano figure, the second movement highlights strings pinging , burning and slashing, with the piano’s chords structurally resonating at first at first, then exchanging spiky figurations with the strings. The more resonant-sounding piano notes beautifully morph into pregnant-like water-droplet notes, as the cello and violin play “out of the air” pizzicato harmonics – the piano finishes as it began, with agitatedly mobile figurations.

Sostenuto-like cello chords begin the third movement, here backed by limpid piano sounds – the violin. something of a decorative, outwardly-defining constant force, plays more tortured figures as the cello muses with the piano – what lovely, long-held notes! – the violin again sounds acerbic, and we hear the “clash of seconds” that the players had demonstrated beforehand, which then gradually resolve – very architectural, solidly-based timbres and tones – from meditative to grand and imposing!. The violin “grows” a lighter, more evanescent outward texture, as the music for cello and piano goes deeper, more inward, the players digging into their tones with rolling figurations – very ‘cello-centred! The violin remains a more quixotic-flavoured figure, here, its tones pointilistic in effect, with harmonics and pizzicati, and in places almost pentatonic-sounding!

The fourth movement has a very pointillistic beginning – knockabout notes from the strings, pizzicato and arco, and the piano very punch-line in effect! The strings are very legato against the piano’s cryptic staccato comments – the movement is very short!

Certainly it all suggests something I feel that’s structural in the music’s bones – I would like to hear it again, being able to relate parts more readily to the whole – there would have been many connective references I didn’t place in context first time round, and am keen to explore that connective tissue aspect of the work relating to architecture and to the ravages of time on any kind of structure given such status by my experience and imagination! It was all brought off with the greatest of aplomb and confidence by the players!

The concert concluded with Dmitri Shostakovich’s deeply personal 1944 Piano Trio in E Minor, composed in memory of the composer’s friend Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky who had died in February that year of a heart attack at the age of forty-one. As with many “documented” incidents on Shostakovich’s life, accounts differ as to when the composer began work on the Trio (principally whether it was before or after hearing the news of Sollertinsky’s death, the latter event even presenting in one account as a rumoured NKVD (Russian Secret Police) murder rather than a heart attack) – however, a certain consensuality (as with the present programme’s notes on the music) places the first movement as all but completed when Shostakovich received the news.

The work’s been represented variously as a requiem, either for one man or for the millions of Russians who perished during the war, as a protest against the anti-Semitism rife in the Soviet Union culminating in the Nazi atrocities committed against Russian Jews in the death camps of the time, and as an indictment of the Soviet System in general under the iron-fisted Stalin, whose censorship of the composer’s music reached its nadir at this time, causing the Trio to be banned from public performance in1948 as “decadent “ and “formalist”. Not until the dictator’s death in 1953 did the work begin to gradually return to favour

It’s now celebrated as one of the greatest of Shostakovich’s works, and part of an enviable “piano trio” tradition in Russia alone – Glinka, Tchaikovsky, Arensky, Borodin, Taneyev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui and Rachmaninov all helped “pave the way” for the younger composer, whose own writing, however, eschewed the prevalent quasi-orchestral textures of the Romantic piano trio, choosing instead a sparser, more transparent sound-picture, not without force and impact, but with a bleaker, and less “cushioned” effect. Shostakovich had always professed an admiration for Jewish music, delighting in what he called its “multifaceted” quality – appearing to be happy when in fact it is expressing tragedy (a quality shared by Mahler’s music) – and this ambiguity of expression comes to the fore in the Trio’s finale, a veritable Todtentanz with macabre associations, more of which below. The work as a whole gravitates from being the composer’s grief for his friend’s death to a catalyst for his feelings regarding the other tragedies whose impact were weighing increasingly heavily on his existence.

What, then, of this performance? In a word, gripping, from its very first intensely spectral harmonic note intoned hauntingly by cellist Ken Ichinose almost at the top of the instrument’s range and soaring above the violin’s conventionally-voiced though similarly elegiac tones and the piano’s basso profundo utterances – the spell’s intensity was palpable, the instrumentation a play of parallel states of being, dream floating alongside consciousness, and both far above deeper and darker reality – within the same being, or with three different beings cast adrift? Briefly, the cello “comes back to earth” then joining the violin in a steady single-note rhythm, exchanging single-note-accompanying and melodic roles as the momentums continue with both tempi and intensities building, until the music swings into a dark-browed and determined jogtrot mode! The musicians seem gripped by the music’s compulsions, pizzicato exchanges, trenchant piano chordings, slashing single-note string utterances, all suggesting some kind of search for a way through, with Monique Lapins’s violin-playing in particular, in places incredibly exploratory!

If respite was sought, it was not to be found in the second movement – Allegro con brio, the music proclaimed, with violin and cello flexing muscle and expiating energies, and further driven along by the piano’s pounding chords and trumpeting arpeggiations. What began as a high-spirited fun dance seemed to get more obsessive and trenchant, descending into repetitions of groaning drone-like tones trapped in their own vortices – a trio-like section almost promised the dance-theme some breathing-space, but the wildness soon returned, pianist Gabriela Glapska’s seemingly endless energies spearheading the music’s drive towards a breathless concluding flourish! Whew!

But then! – bleakly spaced-out piano chords seemed to slice the ambiences pitilessly into shards, with first the violinist and then the ‘cellist picking up from the fragments a tragic, elegiac theme – a Passacaglia, with violin and cello continuing to play variants of the theme over the piano’s repeated sequences. The sense of desolation grew with the instruments’ gradual descent into depths of sorrow, the mood at its darkest suddenly interrupted by the piano beginning an insistent, hypnotic rhythm ,and introducing the Mahlerian irony of a Yiddish-like dance, one whose themes the composer would repeatedly use in his later music (Shostakovich later described them as dances of death and despair, perhaps mindful of accounts he had heard of atrocities such as Jewish prisoners in the “death camps” made to dance on their own graves by their Nazi captors before being executed).

I found this music extraordinary, even almost hallucinatory jn places, thanks to what seemed like the three performers’ total and unstinted immersion in its composer’s world. The build-up to the music’s ironic interplay of humour and savagery in the finale was overwhelming, with the gradual evaporation of that nightmarish scenario right at the work’s end leaving one utterly drained and aghast at what one had just been told.

Even among what must surely seem for Wellington Chamber Music over recent times like a plethora of outstanding performances, this one by the superb Ghost Trio had, I thought, something uniquely special to return to in one’s memory and relish anew.

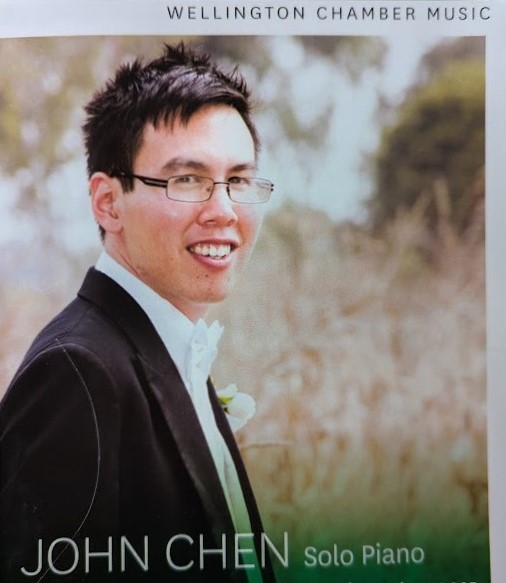

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich Orchestra Wellington with Marc Taddei rehearsing Shostakovich

Orchestra Wellington with Marc Taddei rehearsing Shostakovich