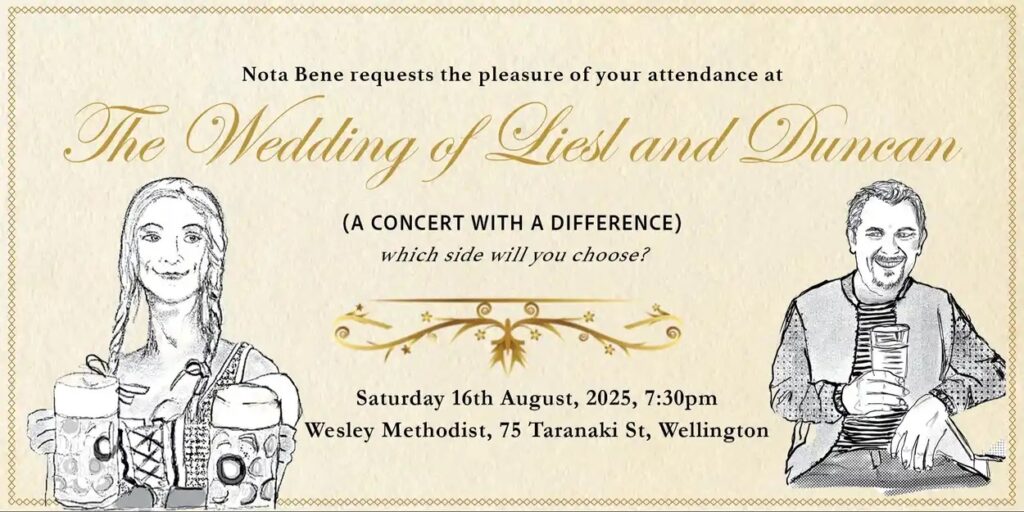

Nota Bene Choir presents:

THE WEDDING OF LIESL AND DUNCAN

7:30pm,16th August, 2025

Wesley Church, Taranaki St., Wellington

Liesl – Barbara Paterson (soprano) / Duncan – Robert Tucker (baritone)

Friends and Guests – Nota Bene Choir

Pianists: Heather Easting / Emma Sayers

Music Director – Maaike Christie-Beekman

Devised, Written and Directed by Jacqueline Coats

Order of Service:

WELCOME – Liesl’s family, friends and guests in the Old Hall

J.STRAUSS Jnr. – Champagne Chorus (Die Fledermaus) – Liesl, with Choir

HAYDN – Die Beredsamkeit (Eloquence) – Choir

LEHAR – Vilja Lied (Die Lustige Witwe) – Liesl, with Choir

SCHUBERT – Der Tanz – Choir

SCHUMANN – Lied der Braut – Liesl – solo

BRAHMS – Sehnsucht – Choir

BRAHMS – Wie bist du, meine Königin – Duncan, solo

SCHUBERT – Schicksalslenker, blicke nieder – Duncan, with Choir

HAYDN – Die Harmonie in der Ehe (Harmony in Marriage) – Choir

SCHUBERT – Trinklied – Duncan – solo

Guests are invited to be seated in the Church

THE SERVICE – Entrance of the Bridal Party

WAGNER – Wedding March from Lohengrin – Choir

BRAHMS – Liebeslieder Waltzer

1. Rede, Madchen, allzu liebes (speak, dear girl) – Choir

Exchange of Vows

2. Am gesteine rauscht die Flut (the tide rushes on the rocks) – Choir

3. O die Frauen, O die Frauen (O women!) – Tenors and Basses

4. Wie des Abends schöne Röte (the evening’s beautiful red) – Sopranos and Altos

5. Die grüne Hopfenranke (the green hop vine – Choir

6. Ein Kleiner, hübscher Vogel nahm den Flug (a small, pretty bird took flight) – Choir

7. Wohl schön bewandt was es (my lover no longer sees me) – Liesl

8. Wenn so lind dein Auge mir (If your eyes are so gentle) – Choir

9. Am Donaustrande da steht ein Haus (By the Danube stands a house) – Choir

10. O wie sanft die Quell – (Oh, how gentle the spring) – Choir

11. Nein es its nicht auszukommen (No, it is not possible..)- Choir.

12. Schlosser auf, und mache Schlosser (Locksmiths, up and make padlocks!) – Choir

13. Vogelein durchrauscht die Luft (Birds fly swiftly through the air) Sopranos and Altos

14. Sieh, wie is die Welle klar (Look how clear the waves are!) Tenors and Basses

15. Nachtigall, sie singt so schön (Nightingale, you sing so beautifully) Choir

16. Ein dunkeler Schacht ist Liebe ( A dark pit is Love!) Choir

17. Nicht wandle, mein Licht (Do not wander, my Light) Tenors

Exchange of Rings

18 Es bebet das Gestrauche (The bushes tremble) Choir

Pronouncement and Celebration

MENDELSSOHN (arr. Nota Bene) – Wedding March

“The Wedding of Liesl and Duncan” – a fertile music-theatre brainchild of director Jacqueline Coats, which makes creative and heart-warming use of the manifold skills and attendant enthusiasms of musicians belonging to and associated with Wellington’s Nota Bene Choir. Readers expecting a conventional review of a group performing a first-half programme featuring a collection of operatic solo and choral items, followed by a second-half presentation of Brahm’s Liebeslieder Waltzes might wonder at encountering, first-up, this introductory plethora of detailed information that could take as long to read through as the actual review itself! I hope the method in my madness at offering this storehouse of elaboration to begin with “sets the scene” for the effusion of delightfully theatrical, and even in places intensely dramatic entertainment which elevated much of the music’s otherwise divertissement-like status into far more connective musical tissue.

Brought into play was a real, infectious sense of a nuptial occasion by (a) the choice of venue, in Wellington’s Taranaki Street Wesley Church, and (b) the theatrical method of incorporating the audience into the actual celebrations. So it was that we were all invited at the outset to join the bride’s family, friends and guests into one of two gathering-places capaciously provided and linked by a corridor (I suspect each simply “filled up” followed by the other, leaving, incidentally, very few spare seats!). At each place was a pianist (ours was the versatile Heather Easting, while the other would have certainly enjoyed the equally capable artistry of Emma Sayers) – after being welcomed by the indefatigable Jacqueline Coats and enjoying some soothing strains of firstly Bach and then Pachebel on the piano, there subsequently appeared suitably-attired guests and friends of the couple to be married, along with the major participants, Liesl (Barbara Paterson) and Duncan (Robert Tucker) who alternated between both of these places, by turns recounting for each of the groups some of the history of their meeting and subsequent engagement.

This “getting to know” first the bride and then the groom was accompanied by the first “Welcome” bracket of songs, beginning with a spirited “Champagne Aria” from J,Strauss Jnr’s “Die Fledermaus” sparklingly (ahem!) delivered by the bride and guests. I found a lot of the spoken commentary from all the characters difficult to make out in that acoustic, sitting as I was at the far end of the group – but I could hear enough to decipher salient detail, such as information pertaining to the non-arrival, thus far, of the groom – a droll chorus (“Eloquence” by Josef Haydn) suitably commenting on various apposite kinds of character traits! To my great pleasure we heard next the ravishing “Vilja Lied” from Lehar’s “Die Lustige Witwe” most plaintively sung by Paterson (with lovely dynamic control of those ecstatic high notes) and echoed by the chorus. Schubert’s “Der Tanz” followed, after which Liesl introduced, a mite confusingly, both her “adoptive’ and “real” parents, in tandem with Schumann’s lovely “Lied der Braut”, Liesl’s solo here blending affectingly with the following “Sensucht” by Brahms, for the choir.

Consternation reigned as Duncan (Robert Tucker), the Groom, suddenly turned up, effusively pressing his suit with another Brahms song, “Wie bist du, meine Konigin!”, beautifully and pliantly delivered here by both singer and pianist. We got some semi-confessional “history” from the singer of a previous relationship and an existing offspring (too much information?) associated with the beseeching “Schicksalsenker” by Schubert for tenor and choir, which captured all hearts, before the groom was off again, “looking for Liesl!”, to the strains of Haydn’s satirical “Die Harmonie in der Ehe”, all boisterous good fun for the choir! Duncan returned, jubilant, and in a time-honoured gesture to blokedom, launched into a Schubert “Trinklied”, extolling Baccchus, “Plump Prince of Wine!” – the wedding was definitely “on!”

The preliminaries having been addressed and given their due, we were enjoined to be upstanding and take ourselves via some of the way we had already come to the church for the ceremony. Our director-cum celebrant fulsomely welcomed our presence, reminding us that before things went any further we needed a bride! – and so we had the lump-in-throat enchantment of the expectantly fresh-toned “Wedding March” from Wagner’s Lohengrin as Liesl and her escort came down the aisle to the altar.

The bride being thus delivered and the groom suitably prepped, our celebrant took the opportunity to “set the scene” with the help of the composer of the aforementioned “Liebeslieder Waltzes”. I had listened to these songs perhaps once before and remember at the time thinking them somewhat underwhelming as regards the “must hear again” department – but what a difference here, brought to life via the bright and sparkling Nota Bene voices, Maaike Christie-Beekman’s exuberant direction, and our duo pianists’ by turns incisive and melting playing – how wonderful for these songs to be given such a vibrant theatrical and even dramatic context! Each one seemed to “possess” its different character, imbuing the normally threadbare three-four trajectories with tangible on-the-spot representations as well as tying together their unifying flow in the larger scheme that held the whole evening together so successfully.

If we had thought the marriage “done and dusted” by then, we were in for a few (almost soap-opera) surprises! – from the beginning, the celebrant touched on the potential “will it happen?” travails of a relationship, underpinned by the first song’s “Rede, Madchen, allzu liebes” (Will you, who rouse passion, relent?”) to which the groom, Duncan, reopened his “confessional” doubts, spurred by the choir’s “Am gesteine rauscht die Flut” (The flood rushes onto the rocks), and the age-old bachelor’s refrain “O die Frauen, O die Frauen” (further elaborated here as “I’d have been a monk were it not for women”). It was time for Liesl to enjoy some affirmation with the soprano/alto voices’ beautiful “Wie des Abends schöne Röte” (How the evening redly glows).

As the vows begin, so do the doubts arise, darkly harmonised by “Die grüne Hopfenranke” (like a creeper stuck in the ground) from the choir, the celebrant suitably agitating and the mothers appearing to give their daughter solace (all superbly theatrical!). Liesl isn’t much comforted by the idea of a pretty bird being caught -“Ein kleiner, hubscher Vogel nahm den Fug” (Christie-Beekman brings out so much more flavour from the choir’s voices in these places than I previously recall!). The bride remains unmoved at first, remembering how “it all seemed much easier when we were young” – “Wohl schön bewandt was es”, and now…….The choir quickly moves to comfort Liesl with “Wenn so lind dein Auge mir” – reassured by gentle eyes, she takes her bouquet as the next song quickly capitalises on the mood – “Am Donaustrande, da steht ein Haus” , sings the choir, breaking through the impasse of doubt as if shattering a barrier of glass! Liesl completes her vow! – triumph!

To the strains of “O wie sanft die Quelle” the couple waltz to the moving waters! Just when it all seems plain sailing comes another cloud – “If any person knows of any reason, etc…..” From the ranks of the choir a man steps forward and confesses his secret love for the bride! – Pandemonium! The Choir erupts with “Nein! – es ist nicht auszukommen!” (No! It’s impossible!”) The couple run away from the tumult as the choir angrily declaims “Schlosser! Auf, und mache Schlösser” (Locksmith! Up, and make some locks!). but peace is soon restored and the errant suitor is dismissed, as the sopranos and altos sing of birds rushing through the air to their rest (“Vögelein, durchrauscht die Luft”) and the tenors and basses extend the peace further with “Sieh, wie ist die Welle klar” .

The nightingale sings, and the world seems to stand still – “Nachtigall, sie singt so schön” intones the choir – Liesl is firmly on the side of love and helps steer Duncan through his “dark night of the soul” memory at “Ein dunkeler Schacht ist Liebe” (Love is a dark pit”), though he’s lost for words at this, the last fence! “Boys, you gotta help me out, here!” his whole aspect is saying, and the tenors come to his aid with “Nicht wandle, mein Licht” – a beautiful reassurance of a homecoming, AND of the appearance of the rings – where? – here! – no! – yes! – with the choir giving the final and clearly affirmative “lift” to the rhythms and tones of “Es bebet das Gesträuche” – (as the bushes tremble with the birds’ flight, so does my soul with desire and fear at the thought of you!). As the couple sign the register and their union is pronounced, so does Mendelssohn’s Wedding March sound and resound as Liesl and Duncan are resplendently (and deservedly) acclaimed! What a journey, and how richly bedecked it all proved, proclaiming Jacqueline Coats’s vision as transformational and the response of all of the performers, conductor, singers and players, something to truly savour in the memory.

Julien Van Mellearts (Renato) and Jared Holt (King Gustavo)

Julien Van Mellearts (Renato) and Jared Holt (King Gustavo) Natasha Te Rupe Wilson (Oscar) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Natasha Te Rupe Wilson (Oscar) – photo, Stephen A’Court Madeleine Pierard (Amelia) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Madeleine Pierard (Amelia) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Emma Pearson as Musetta

Emma Pearson as Musetta John Chen – French Piano Music Recital

John Chen – French Piano Music Recital