Wellington Opera presents:

GIACOMO PUCCINI – Tosca (opera in three acts)

Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa & Luigi Illica

Cast

Cesare Angelotti – Samson Setu (bass)

Sacristan – Wade Kernot (bass)

Mario Cavaradossi – Jared Holt (tenor)

Floria Tosca – Madeleine Pierard (soprano)

Baron Scarpia – Teddy Tahu Rhodes (baritone)

Spoletta – Manase Latu (tenor)

Sciarrone – Morgan-Andrew King (bass)

Jailor – Brent Allcock

Boy – Ivan Reid

Wellington Opera Chorus

Chorusmaster – Michael Vinten

Orchestra Wellington

Conductor – Brian Castles-Onion

Director – Jacqueline Coats

Set Design – Michael Zaragoza

Costume Design – Rebecca Bethan Jones

Lighting Design – Rowan McShane

St,James Theatre, Courtenay Place, Wellington

Wednesday, 11th September 2024

(also September 13th, 14th, 15th)

This was, I thought, a “Tosca” from Wellington Opera to be relished. Giacomo Puccini’s three-act melodrama, has since its appearance fronted up to and triumphed over certain critical attitudes struck towards it that were, to say the least, less-than-positive. Critics both contemporary and retrospective have castigated the work with phrases like “three hours of noise”, “disconcerting vulgarities” and with a “tiresome, silly and gullible” heroine – and Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich once replied to being asked about “Tosca” with the words “A great opera, but terrible music!” The invective surely reached its peak more than thirty years after the composer’s death via musicologist Joseph Kerman’s 1956 publication “Opera as Drama”, in which Tosca is summarily dismissed by the author as “A shabby little shocker”!

However, singers, conductors, directors and the general opera-going public have regularly defied and confounded such judgements, with the work recently ranked as the fifth most-performed opera in the world by the global opera data-site Operabase. Even if popular opinion and response hasn’t always necessarily reflected critical opinion, Tosca has flourished with flying colours thanks to its plot’s readily melodramatic scenarios, its vividly-wrought characterisations of the three main protagonists, and the enduring emotional “tug” of its two great arias, “Vissi d’arte” for the soprano and “E lucevan le stelle” for the tenor.

Director of this production, Jacqueline Coats, described the work as essentially a love story with a tragic outcome, one determined by outward forces which ultimately over-ride the personal concerns and aspirations of the protagonists. And on a wider political level one of those forces exerts his power to maintain a status quo of tyranny while simultaneously seeking to manipulate the fate of the two lovers for his own ultimate gratification. It’s an interplay of situation that feels both Homeric and Shakespearean, not to mention more recent contemporary resonances.

The joy of Coats’ direction was, for me, its unswerving focus on the interplay of these ruinously conflicting circumstances, in which the conflicting strands of the drama were allowed their full-blooded resonances. Everything was amply voiced and energised by the focused commitment of the singers, conductor and orchestral forces, and (particularly in the first two acts) the powerful simplicity of the stage settings, beautifully and atmospherically placed and lit for maximum effect. Nothing was allowed to distract from the essential fatalism of the work’s unfolding, even if I was initially nonplussed by the mysterious corpse who appeared at the Third Act’s beginning, thinking it belonging perhaps to a prisoner who’d fallen from the tower of the Castel Sant’Angelo while unsuccessfully attempting to escape (my sharper-eyed companion whispered the name “Angelotti” in response to my inquiring sideways look!). I was also surprised by the unexpectedly onstage “shepherd-boy” singing his folksong (admittedly rather beautifully) before being led away by his companions, and by groups of what seemed like various prisoners either in transit or allowed the freedom of a few minutes of fresh air before being reconfined.

The production maintained the story’s “Roman” setting throughout, from Act One’s traditional church interior scenario through Act Two’s depiction of the iconic image of a wolf feeding the twins Romulus and Remus surmounting the scene. This image presided over a more twentieth-century “look” to the headquarters of Baron Scarpia, the Chief of Police, its walls alternating iron-grey and blood-red pillars with menacing intent. Costumes reinforced a more contemporary, if non-specific sense of time, with Floria Tosca’s suitably beautiful and florid, her lover, Mario Cavaradossi’s casual and workman-like, and Baron Scarpia’s austere and business-like, with the latter’s minions (Spoletta and Sciarroni) suitably institutional.

The opening church interior scene with its “ecclesiastical” lighting amply engendered a kind of timelessness, reinforced by the contrasts with a near-contemporary-art Madonna statue, and the modern dress of the congregation who came to enact the concluding Te Deum. Here, the interplay between voices, bells and intermittent cannon-fire made by turns a splendidly celebratory and disturbingly remorseless impression – at once a kind of reminiscence of and antithesis to the exuberant energies of the conclusion to the Second Act of the composer’s “La Boheme”. In this very different résumé, it was all brought off superbly!

Vocally and dramatically, the work got an appropriately atmospheric start with the wonderfully black-voiced Samson Setu as the recently-escaped prisoner Angelotti seeking concealment in the church, the orchestra properly conveying his “flight” with urgent, desperately-voiced impulses. The subsequent appearance of the Sacristan, Wade Kernot, provided much comic relief in complaining of having to run around after his charge, the painter, Cavaradossi (currently at work in the church) and keep his brushes clean and his paints in order – a lovely, amusingly “holier-than-thou” cameo portrayal.

As Mario Cavaradossi, Jared Holt “warmed” and filled out his voice as the evening progressed – his early “Recondita armonia” I found precise and accurate but a touch effortful, as he seemed in places throughout this first scene when duetting with Tosca. What a change, however, had come over his delivery by the time he reached his second-act “Vittoria! Vittoria!” outburst of defiance of Scarpia – he was like a man possessed, completely inhabiting his energized person – a terrific performance! And he then realised with equal force the spectrum’s opposite and despairing end with a heartfelt “E lucevan le stelle” in the third act, when facing his execution and the loss of Tosca. It all made his tender “Amaro sol per te m’era il morire” to his beautiful would-be rescuer all the more poignant.

No greater contrast could be imagined than with the Baron Scarpia of Teddy Tahu Rhodes, a portrayal which sated all of his scenes with the character’s essential brutality. I could have imaged a suaver, more vocally charming (and perhaps, therefore, even more dangerous) Scarpia – but his was a character obviously accustomed to getting what he wanted, and the unrelenting coruscating quality in the voice purely and simply gave tongue to that same quality In his character. Those wonderful soliloquies in both the First and Second Acts which revealed to us his remorseless drive and his insatiable desire for the thrill of sexual conquest made their mark with absolutely no doubt or misgiving, no skerrick of a qualm.

Against this rock, this seemingly immovable object, was cast the irresistible force of his adversary-cum-object-of-desire, Floria Tosca. I have to say that, in experiencing Madeleine Pierard’s astonishing portrayal, I was so taken up with the whole-heartedness of her characterisation I never once gave a thought of any other Tosca I’d seen or heard – from her very first entrance after her off-stage cries of “Mario! Mario!” when seeking her lover, Cavaradossi in the church, she gave to us as intense and all-encompassing a character as was her adversary-to-be, but in her case one filled with so much light-and-shade that one found oneself revelling in her sheer presence – her humour, her quixotic changes of mood, her passionate utterances, her tenderness and her moments of both desperation and resolve.

To pinpoint everything she did to bring the manifold aspects of the character to life would require an essay for which there would be no time or space here, and, certainly, in places produce a “words fail me” result. Suffice to say that for me it was an utterly memorable performance, one whose heart-melting “Visi d’arte” represented for a few precious moments a kind of entering into the apex of the dramatic soprano’s art. But also, it was an undertaking which in itself paid tribute to the quality of interaction between her and her two principal onstage partners. As much as did any of the individual performances discussed above, it was a give-and-take quality which helped make this “Tosca” such a special musical, theatrical and dramatic experience.

I hadn’t encountered the well-rounded voice of the Sciarrone, Morgan-Andrew King, before, but I had of course, previously heard the Spoletto, tenor Manase Latu, in a completely different operatic world, that of Rossini’s “Le Comte Ory”, the juxtapositioning of the two roles in my head alone giving me a kind of refracted pleasure in having such a different experience from a voice this time round! I’ve already mentioned the “shepherd boy” and his lovely folk-song at the beginning of Act Three – a young man, Ivan Reid, whose beautiful tones could well take him places. The choruses played their impactful parts in the awe-inspiring “Te Deum” that closes the opera’s first Act, as well as mellifluously underpinning the first part of Cavaradossi’s fateful interview with Scarpia in Act Two.

Heroes of a similar “cut” were conductor Brian Castles-Onion and his players, Orchestra Wellington, supporting all the singers up to the hilt, and responsible for some equally stirring and heart-melting sequences throughout the evening – what springs to mind are, of course, the “Scarpia” moments, delivered by the brass with the utmost vehemence, and the contrasting episodes of tenderness from strings and winds – playing in my head at the moment is the clarinet theme which introduces Cavaradossi’s third-act “E lucevan le stelle”, for instance – and alternating with the ominously-cheerful early-morning strains of winds and bells heralding the new day, which begin the same third act. All was part of that overall impression of an embodiment of something special.

I dips me lid in gratitude to Jacqueline Coats – her sensitive overall direction resulted in a production which seemed to me to enable the work to speak its own innate character (which is increasingly rare in an operatic world bedevilled by, in the words of Michael Flanders of “At The Drop Of A Hat” fame, the impulse of “Anything to stop it being done straight!”). Her team of Michael Zaragoza (set design), Rebecca Bethan Jones (costume design) and Rowan McShane (lighting design) were all obviously on the same wavelength, with a result that, as I’ve indicated above, gave us what seemed like “the real thing”.

All the more reason to rail against the news, contained in a note in the programme, that Creative New Zealand has declined funding for Wellington Opera for 2025. It will be no surprise, of course, to the politically aware who read this, considering that the arts in general seem more-than-usually under siege via the present Coalition Government’s current strictures. Creative New Zealand will, of course have its priorities within the framework of its own limited resources – the problem is a much bigger picture which poses the question in (and towards) our society of “What’s important?” Let’s hope we can convince more of those who need convincing that among what constitutes the right answers to that question are the arts! – and Wellington Opera’s Tosca has just furnished palpable proof that such is very much the case!

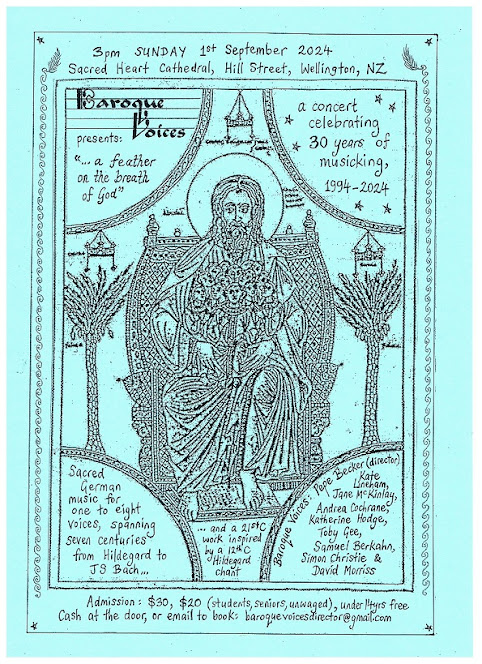

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach –

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach – Baroque Voices 2024

Baroque Voices 2024

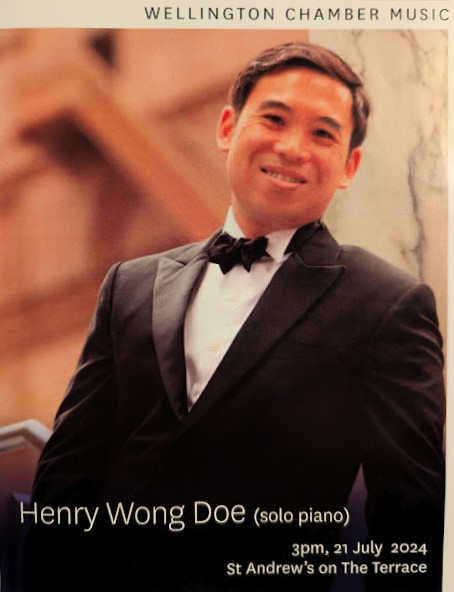

Wellington Chamber Music presents :

Wellington Chamber Music presents : Two performances: Wellington Cathedral of St. Paul, Molesworth St.

Two performances: Wellington Cathedral of St. Paul, Molesworth St.

Duo Enharmonics – Beth Chen and Nicole Chao (piano duo)

Duo Enharmonics – Beth Chen and Nicole Chao (piano duo)