JOHN PSATHAS – Leviathan

Four Percussion Concertos

The All-Seeing Sky (with Fabian Ziegler and Luca Staffelbach)

Call of the Wild (with Adam Page)

Leviathan (with Alexej Gerassimez)

Dijnn (with Yoshiko Tsuruta)

All with Orchestra Wellington and Musical Director Marc Taddei

Orchestra Wellington OW 23CD

Hailed as “genre-defying music”, four of New Zealand/Greek composer John Psathas’s percussion concertos have made a spectacular appearance on Orchestra Wellington’s own label, a release appropriately gathered together under the name of “Leviathan”, the title of one of these concertos. The “genre-defying” aspect reflects Psathas’s intense feelings concerning the role of a contemporary composer, which he feels is a matter of “connection” across all genres and boundaries, one which reaches out to all audiences. For him this “outward” energy conveys that connection, and it has come to inform works such as the four presented on this album. Significantly, Psathas regards Beethoven’s music as an exemplar of such “reaching out” to people, music that embodies, in his words, “that desire to reach another human being”.

All four of these concertos were recorded during Psathas’s “composer-in residency” tenure with Orchestra Wellington, a circumstance that has given him a good deal of joy – “we had these incredible soloists and we had fantastic performances, and we’ve captured them”. As well, the venture is obviously a tribute to the staunch support for Psathas’s music from the orchestra’s Music Director, Marc Taddei. I’ve not been able to comment on the vinyl format of this release as I’ve only seen the CD format (which, in terms of my own reactionary sensibilities regarding recordings in general, has what I would call the “minimalist” approach to presentation, with no accompanying documentation regarding either the works or their performers, save a QR code which you scan for access to liner notes (“Not I, but some child, born in a marvellous year….” etc.! – however, my own “marvellous child” was able to guide me through these personal “portals of Dis” with nary as much as a backward glance!).

The first of the set’s four percussion concerti, “The All-Seeing Sky” is dedicated to the soloists in the recording, Fabian Ziegler and Luca Staffelbach. A “double concerto”, it has three movements – The Portals of Dis, The Upper World, and the titular The All-Seeing Sky – and it entrances the listener at the outset with its almost subconsciously-heard impulses, a process characterised by the composer as “a very subdued oh wow, this is actually happening kind of feeling”. Of course, the opening movement’s title “The Portals of Dis” suggests something dismal and dark, a kind of penetration of an Underworld (as suggested by Psathas’s reference to Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy” which he had read, and which characterised for him a sense of antiquity and ancient times, furthered for him by artist Gustav Dore’s nineteenth-century visualisations of the poet’s journeyings through the Inferno – and yet the opening paragraphs of the music evoke more mystery and eeriness than fear and dread as the travellers in the boat in Dante’s poem cross the River Styx, the sounds of the orchestra detailing the almost limitless wonderment of these adventurers amid their surroundings, as the two soloists – Fabian Ziegler and Luca Staffenbach – gradually but inexorably advance the sense of a “journey” with their increasingly compulsive and addictive patternings on, respectively, the marimba and xylophone. Whole sequences of minimalist patternings alternate with newly-wrought material from both the soloists and the orchestral musicians, gradually intensifying the ambiences with extra percussion – timpani and cymbals – and achieving what Psathas describes as a “welcoming fanfare” to the Gates of Dis. It’s one where the traditionally spectral “abandon hope all ye who enter here” mindset of antiquity is leavened by a more modernist view of one’s mind being “its own heaven and hell” (Psathas suggests in so many words a similarly updated view.).

The following movement, “The Upper World” delivers a new kind of eeriness, with the soloists floating and arpeggiating over a series of deeply-voiced slowly-undulating gestures from the orchestra’s lower instruments, striking an occasionally more forceful, and by turns an exquisitely-flowing air with winds and strings, the atmosphere more claustrophobic than free, as if further reminding us that our “Upper World” can take on similar threatening propensities to that of antiquity’s visionary horrors, with the dismissal of a traditional God plus the trappings creating a vacuum filled by any number of entities bent upon dominance of peoples’ minds. This is further explored by the freewheeling third movement “The All-Seeing Sky” – a kind of “juggernaut” through the void, for much of its length, with the kind of energy that freedom brings, along with a price that has to be paid for that “freedom” – it isn’t long before the exhilaration develops an obsessive, hectoring note, breaking off at the climax to sound a warning – the orchestra builds frightening vortices against whose sides the percussionists hammer until the reality of a new kind of imprisonment hits home. In a tremendous crescendo, begun quietly and almost innocently, both soloists define the formidable slopes that have to be climbed and the spaces that must be filled with new resolve, building the sonorities in a do-or-die effort which awakens the entire orchestral forces who play above their weight, reaching a hammering climax of renewed hope – Psathas elaborates here on his idea drawn from his Greek ancestry of a “gladdening sorrow” – in his own words “gratitude for being alive, and sorrow for understanding all that’s ill in the world!”

Following this on the set’s first disc is Psathas’s “Call of the Wild”, a concerto for tenor saxophone and orchestra commissioned jointly by Orchestral Wellington and the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra, the recording here presenting the work’s actual 2021 premiere given on July 17th by saxophonist Adam Paige and Orchestra Wellington. My “Middle C” colleague, critic Lindis Taylor, reviewed this concert in glowing terms, struck as much by the work’s “vividly individual” nature as by the brilliance of the performance by soloist Adam Page, and of the orchestra under Marc Taddei’s direction. Taylor highlighted the soloist’s “flamboyant confidence” and noted the latter’s use of a “wide range of techniques” as the music unfolded. The instrument itself, while not a standard symphonic orchestral instrument, has long enjoyed imaginative instances of use by various composers – I would have added Vaughan Williams’s name to the list my colleague proffered (for the review see https://middle-c.org/2021/07/orchestra-wellington-under-taddei-with-adam-page-triumphant-in-psathass-saxophone-concerto/).

Solo saxophonist Adam Page describes in his accompanying notes how musical collaboration often has a kind of “jewel in the crown” quality for artists, even though these experiences are sometimes isolated and short-lived – but with the “Psathas/Page” partnership a true friendship (Page calls it “a lifelong connection”) evolved from the pair’s first collaboration in 2012 when co-writing “The Harvest Suite”– consequently Page “jumped/bomb-dived” at the chance of renewing his creative association with Psathas via a new tenor saxophone concerto the composer was formulating.

Psathas’s description of this work’s genesis encompasses a good deal of his family history, dealing with events that left an indelible and continuing mark on both the twentieth and the present century, but more immediately on his own family – his grandparents and great-grandparents were forced to relocate between Greece and Turkey in the early 1920s in what could only be described as devastating and denaturalising circumstances – in the wake of genocidal activities between various racial and religious groups exacerbated by the 1914-18 war in Europe, the governments of both Greece and Turkey deemed it necessary to forcibly relocate ethnic groups whose religious beliefs and cultural mores had become regarded as incompatible with the respective majorities of their citizens, despite the long-established (in many cases) native and indigenous ties these people had created over centuries within what they considered their homelands. There had already been genocidal massacres of non-Turkish Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians both before and after the war and by the time the Governments had signed the 1923 Convention Exchange (called The Asia Minor Catastrophe in Greece), resulting in about one-and-a-quarter million people arriving in Greece from Turkey and over 300,000 Muslims expelled to Turkey by 1923. A Muslim Professor, forced from his home in Crete, to Turkey, expressed in an interview every migrant’s tragedy – “Born in one place, growing old in another place – and feeling a stranger in both places”.

Psathas’s grandparents and great-grandparents experienced the forced marches sustained by people expelled from Turkey during this early 1920s period, resettling in Greece, only to experience a second World War and a subsequent civil war, from which their children (Psathas’s parents) left to emigrate to New Zealand to begin a new life in 1960.. Though he was born in Wellington, most of John’s childhood, along with a sister, was spent in Taumarunui, after which he attended college in Napier. His interest in music developed throughout this time, resulting in his entering University to study piano and composition at Victoria University of Wellington. John’s parents and sister Tania returned to Greece to live in 1988, but apart from trips back to Europe to reconnect, John has remained in Wellington, and he and Carla, his wife, have two children, Emmanuel and Zoe.

Unusual as it is to explore the biographical aspect of a composer to such an extent in a review as here, the works on this CD recording each relate singularly to Psathas’s life experience and familial ties, none more directly that this work “Call of the Wild”. In three movements, Psathas by turns characterises and meditates upon the salient features which define each of his parents, and their heritage and life-experience as embodied in Psathas’s own children and their attitudes and impulses.

Call of the Wild begins with a piece of music dedicated to John Psathas’s mother, Anastasia given the title by the composer “She stands at the edge of the incomprehensible” – a saxophone solo at the beginning, an opening up of a sonic world with which the soloist can play, dominate, integrate, lead or dissolve into. The orchestra becomes the world, giving the energetic impulses of the soloist a sense of direction and unlimited purpose, resonances that seem to have the capacity that resound for all time, in places demonstrating a determination above all else, unquenchable energy of the kind that seems to feed itself – though an almost heart-stopping moment is when the saxophone seems to challenge the limitations of existence itself, sending out a call whose reach is as high as its compass suggests it would allow before pushing even further. Even the surrounding resonances are amazed, perhaps agog at the temerity of this instrument, this single entity pitting its capabilities against the business of being. And then, as if some kind of reassuring synthesis is needed, the saxophone and orchestra come together, surging towards a corelated kind of ecstatic outpouring, then setting an inexorable course towards continuance.

How different is the following, opening with slow, dreamy oscillations of some kind of prenatal nature, Psathas’s father Emmanuel perhaps waiting in the womb to be born, or else meditating the nature of the circumstances of that event in later life. The music suggests a time for reflection upon things that are important to know, feel and conceptualise – in a way it could be characterised as the inner life of the first movement’s outer being, an idea of fusion having different though accessible natures, and each giving to and feeling from the other, Psathas stressing unity of different personalities, spirits, souls. Or it could claim its independence from the outset (Psathas’s title “He can worship it without believing it” suggests this), elaborating upon what the composer considered to be his father’s “staggering force of will” in being “inflexible in his principles of decency and fairness”. Throughout this piece the sounds are unwavering in their constancy and disarming in their quiet persistence and surety. Something of the depth of emotion this piece explores by association is the quoting by a solo violin of a vocal line from the composer’s 2016 work “No Man’s Land”,

From the outset of the third movement (“Tramontane”) there’s a restlessness, both in the setting of different (three-against four) time-signatures for the soloist and the orchestra, which, after a confrontational build-up fuses energies and begins a more concerted exploration – dramatically reducing the pace and the dynamics brings the piece’s elements together, agreeing on the agenda, and setting off again with near-irresistible resolve. This is Psathas’s and his children’s heritage (the name Tramontane literally means “From the other side of the mountains”, and refers to a particular Mediterranean wind which frequently blows up a storm), the composer characterising the energised impulse within his family “to fight for what we needed in life” after his relocation in small-town New Zealand and having to endure being “outsiders” in terms of heritage, custom and religion. What emerges is an incredibly wild ride on the part of the music’s various elements, the soloist’s giving vent to a contemporary “Call of the Wild” in his instrument’s at times frenzied tessitura against the orchestra’s similarly restless soundscapes. In conclusion Psathas comments on the near-inevitability of his children having inherited the same impulsive desire to express what he calls “that nomadic gypsy impulse” and take it to who knows where?

Turning to the set’s second disc, first up is the piece that gives the collection its overall name “Leviathan”. This work, completed by Psathas in 2020, was commissioned as part of an international project with the title “Beethoven Pastoral”, an initiative by the UN Climate Change and BTHVN2020 to promote action on climate change and the environment during the 250th anniversary year of the birth of Beethoven. The Project represented a “determination to be part of the solutions to current planetary challenges’ and the desire “to inspire and be part of that change”. Psathas wrote this work for and dedicated it to Alexej Gerassimez, the soloist in this recording.

“Leviathan” has three movements, summarised as follows – the opening Hightailin’ to Hell crystallises both the composer’s introductory remarks and the feelings generated by the music – “Our planet is in a very bad way, and it seems that we can’t wait to get to the “finish line”. To this end, the human race’s “out-of-control race to environmental disaster” is depicted by the use of “junk-percussion” – The trajectorial impulses are remorseless – the pulsatings never let up as the journey takes the listener through what seems like a thankless and unforgiving, almost lifeless kind of terrain, an experience that gives a feeling of being driven rather than driving – I was put in mind of connections with similarly “driven” music such as Hector Berlioz’s “Ride to the Abyss” from La Damnation de Faust, and (during the most frantically virtuosic sequences) parts of the first movement of Carl Nielsen’s Fifth Symphony during which a solo side-drummer is instructed to try and halt the orchestra’s progress at all costs with savage interjections and disruptive counter-rhythms!

The Final Brook , a homage to Beethoven, comes next – a complete contrast, limpid, shimmering, effusions of light and sensation with instruments that suggest the play of light on and through water, a sound-world I to which one can give one’s sensibilities over to entirely and feel refreshed and renewed, while at the back of these instruments the strings are beginning to playing the actual music of Beethoven’s “Pastoral Symphony” in a dream-like, trance-like way – a “fled is that music? – do I wake or sleep?’ kind of sensation, one which puts Beethoven’s hymn of praise to nature to the forefront of the madness of today’s polluted world.

A single plastic water-bottle used as an “instrument” by the soloist centres our attention throughout Soon We’ll All Walk On Water – a movement one cross-furrowed with dippings, splashings and “impingings” on our sensibilities, with an eerie cosmic circle of sound sensation revolving around the dancing plastic object – a symbol of the madness threatening our world with ruin.

Finally, there’s A falcon, a storm or a great song – (a quote from a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke) – a determined tattoo-like pulsating over luminous orchestra chordings which come and go like fog lights in the gloom, and a grand brass statement reinforced by percussion and driving tones – a held chord, and jagged rhythmic slashings indicate that action is being called for and, indeed demonstrated by the vigorous rhythmic patternings and the long-breathed calls across the sound-spectrum. The sounds make a stirring impression, even though they can at times tremulously fall back as if lacking certainty, but then gather and plunge onwards after a dramatic pause – obstacles appear out of nowhere and are subdued and conquered – it can be done, and human beings, whether falcons, storms or great songs, can be inspired to act with such purpose! – in the composer’s words, “of steel and drums and momentum and drive!” Percussionist Alexej Gerassimez and the orchestra players are heroes, every one, under Marc Taddei’s unswervingly focused direction!

Rather more elusive, mercurial and mysterious as a creation is Djinn, a 2009 work which Psathas first crafted as a marimba concerto for Pedro Carneiro, but which has since appeared in various other guises. The soloist here, Yoshiko Tsuruta, remembered the premiere of this concerto well, and was honoured to be invited to present this work in 2024 – in her words, “an exciting and deeply-rewarding experience”.

Djinn is a marimba concerto in three movements – 1. Pandora – 2. Labyrinth – 3. Out-dreaming the Genie. The first movement is a meditative dialogue between soloist and orchestra depicting the legend of Pandora, who opened a box containing all the evils of the world, leaving only hope inside for humankind. – though distinctive, the movements are interconnected by a common mythological resonance where consciousness and mystery can interact and colour both our individual and collective imaginings. The second, Labyrinth, is perhaps the most profound as it symbolises a journey of self-discovery and has the capacity to surprise and astonish us, despite our expectations. The final movement, Out-dreaming the Genie offers a kind of interpretation of these previous experiences as

sources of hope, confidence and freedom as one might imagine it could be. The soloist, Yoshiko Tsuruta, gives an extraordinary performance, never missing a beat or nuance, and Marc Taddei and Orchestra Wellington lead us through the proverbial maze of exploration, entanglement and eventual realisation with single-minded resolve and a degree of hope bolstered by determination – the music in both its performance and symbolic power becominga synonym for human perseverance.

So, what feelings am I left with about what I’ve been listening to? Mainly that, to go into and through these pieces, either separately or together, is to undertake a journey that puts one in touch with things that ebb and flow, and helps one crystallise one’s feelings about music in general and about humanity and ITS relationship with music. After listening to these works by John Psathas on this recording, the most resounding thing I’m feeling is to equate music all the more with being human, and reinforce that quality of sharing something that’s about continuance – as someone put it so succinctly, like ”a journey on an overgrown path”. To be thus presented with such a simple yet profound idea is a wondrous achievement – one that I urge people who haven’t yet done so to try through this splendid set of recordings of John Psathas’s music.

“Turtle Time” with speaker Jonathan O’Drowsky, and conductor Robert Oliver.

“Turtle Time” with speaker Jonathan O’Drowsky, and conductor Robert Oliver. Some of the performers at the conclusion of “Jack@80” at St. Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace Church, Saturday 12th October, 2024

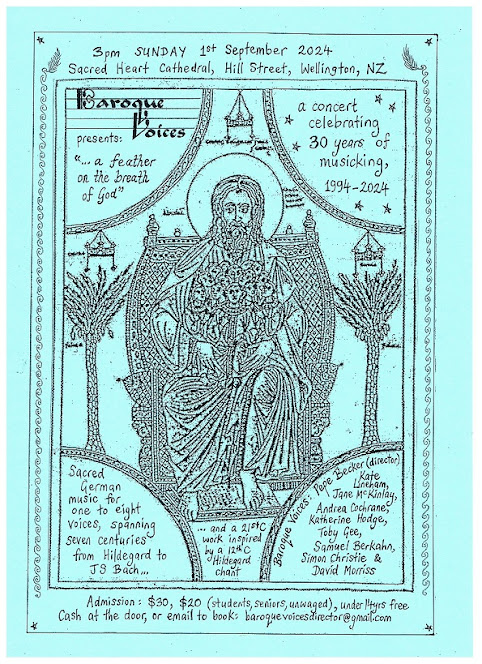

Some of the performers at the conclusion of “Jack@80” at St. Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace Church, Saturday 12th October, 2024 Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach –

Baroque Voices – From Hildegarde to JS Bach – Baroque Voices 2024

Baroque Voices 2024

David Morriss (bass), Pepe Becker (director, soprano), Douglas Mews (keyboards), Robert Oliver (bass viol)

David Morriss (bass), Pepe Becker (director, soprano), Douglas Mews (keyboards), Robert Oliver (bass viol) Futuna Chapel, Karori

Futuna Chapel, Karori