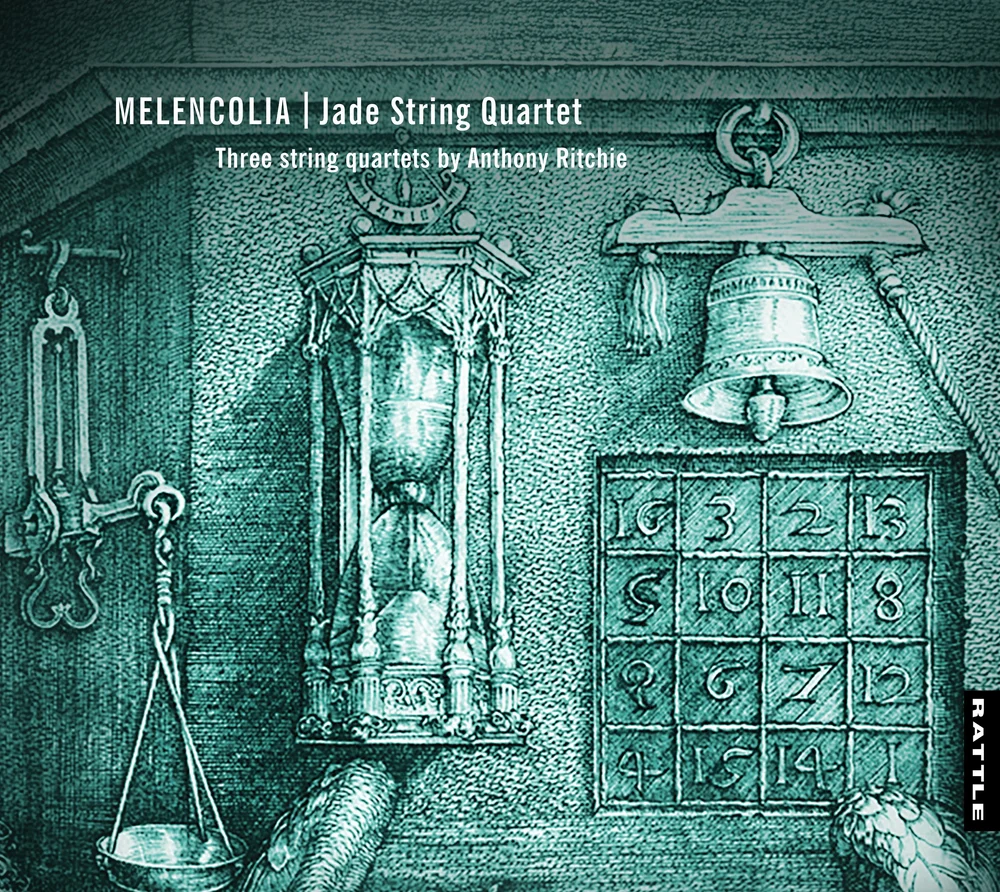

MELENCOLIA

ANTHONY RITCHIE’S STRING QUARTETS 1-3

Jade String Quartet

Miranda Adams, Charmian Keay (violins).

Robert Ashworth (viola), James Yoo (’cello)

Producer: Kenneth Young

Engineers: John Kim, Steve Garden

RATTLE RAT-D159 2025

After first-time listening right through in a single, totally absorbed (occasionally transfixed) sitting to a recently issued Rattle Records recording of Anthony Ritchie’s three string quartets, here played by the remarkable Jade String Quartet, I found myself afterwards wishing my tongue could utter the thoughts that arose in me!

Rousing myself from the daze I’d drifted into, I couldn’t help thinking of a similar “body” of works I’d recently been made familiar with to an unprecedented degree – the string quartets of another composer, Dmitri Shostakovich, whose music has been “spotlit” here in Aotearoa New Zealand, during the latter’s 50th death anniversary year. It simply and suddenly occurred to me (I freely admit, on an acquaintance that was, at this stage, hardly in-depth in either case!) that both composers seemed to have taken pains to reserve a certain concentrated quality of utterance for the string quartet medium.

In Shostakovich’s case, beleaguered as he was for writing “public” music (symphony, opera, concerto, cantata) which didn’t “conform” with the authorities’ need for artists to produce “uplifting, positive-sounding” works that reflected the joys of life under the rule of the great dictator, Josef Stalin, the composer turned to the “more private” medium of the string quartet to utter those personal aspirations, comments, and criticisms which for many years couldn’t be made in public. Only with the death of Stalin in 1953 was any kind of freedom of expression mooted for artists, and even then and afterwards there were disapproving “official” voices raised against some of Shostakovich’s later works.

Hardly a jot of semblance links Shostakovich with Anthony Ritchie regarding the conditions under which they wrote their music, except for the fact of both having to wait long periods for certain of their works to be performed after composition – Shostakovich 25 years after the composition of his 4th Symphony, Ritchie a whopping 37 years for his First String Quartet to be premiered after its completion! What forcibly struck me when hearing the Jade Quartet’s stupendous new Ritchie recording was the music’s startling originality and definitive focus, a “this is what I mean” kind of voice that I found put me frequently in mind of the Russian composer with his string quartets, and the single-mindedness of those uncompromising utterances.

Anthony Ritchie

Ritchie’s three quartets reach over a period of no less than forty years, with the first one written in 1983, while the composer was studying in Hungary at the Liszt Academy in Budapest, researching the music of Bela Bartok for his PhD. Writing music in such resonating surroundings could have made it difficult to fetch up a properly distinctive voice, but in the First Quartet’s opening Solo viola and trio Ritchie’s deep-browed solo viola voice straightaway captures something in the folkish air that awakens different responses…. such that could perhaps prove both accompanists, and even further, themselves become caretakers of the journey.

Quartet 1 has overlapping 7/4-like phrases, with beautifully- and delicately-inversed vertical figures, morphing into and out of pizzicato, as the motif plays “lost-and-found” in a plethora of activity. The bows bounce upon strings, then each theatrically lapses into sequences of theatrical recitative as the others gossip in pairs – “What a rude glissando! – Yes, wasn’t it!”. The reputedly 7/4 rhythm returns, with arco, pizzicato – and silence! The next Solo ’cello and trio opens exotically, with folkish phrases and “turns”, before the solo cello enters, working wonderfully declamations into the line, before unaccountably appearing to fall asleep! Are the other instruments then dreaming the ‘cello, or is the ‘cello dreaming them?

Quartet 2 delightfully plays “catch-me-if-you-can” passages, with cheeky “portrait” poses taking turns before being off again, entangling themselves convivially in each others’ figurations! – exhilarating! – More reflections, before there’s a surreptitious swoop, and exclamations of “pretend fright” before the façade is gone without a trace. Immediately, more serious business arrives in Duets – gone are the triplet-rhythmed fun-and-games, for these are the heavies, working in pairs, and not even the most impassioned pleas will stop them, it seems! A respite is brief, as the attack resumes from the air, but the responses hold their ground!

The tumult slows and morphs into Quartet 3 without a break – a disjointed world with its inhabitants trying to join forces with growing intensities and desperations! – Again, we’re taken straight to the next and last movement, Four solos – each vying for supremacy, pleading its case, so eloquent and piteous! – the tumult gradually ceases as the voices realise they have done what’s possible and viable for themselves and for one another – and we suspect that it’s the viola who returns to have the last word!

The Jade String Quartet: Robert Ashworth (viola), Maranda Adams (violin), Charmian Keay (violiin), James Yoo (‘cello)

The Jade String Quartet: Robert Ashworth (viola), Maranda Adams (violin), Charmian Keay (violiin), James Yoo (‘cello)

The Jade String Quartet has more-or-less taken over guardianship of this astonishing work of late, giving only the second public performance in Auckland last year (2024), and subsequently making this recording – the group’s espousal of the work’s determinedly-focused sense of youthful adventure on the composer’s part will surely win the music many new friends.

As for the equally compelling String Quartet No. 2 (2003), the work was commissioned and premiered by the Nevine String Quartet on a Chamber Music New Zealand tour, the group then then recording the work for Atoll Records on a CD (Octopus – Atoll ACD112) which featured several of Ritchie’s chamber music pieces. Less immediately recorded than the Jade Quartet, the Nevine’s reading brings out more of the work’s spaciousness and, particularly in the second movement, an attractive “Whistler-like” ambience, the music’s blue-grey colourings and lullabic tones at once so suggestive and evanescent. Elsewhere, the newer recording’s closer balance and the Jade’s sharper and more volatile responses engage the listener in what feels like a more tactile and primitive kind of engagement – the music’s swaggering gait at the very beginning has tremendous physicality, and contrasts beautifully with the “sighing” sequences that decorate the later ostinato passages, the ending’s piquant gesturings drawing us wonderingly into the silences.

Wonderful writing throughout the Like a Lullaby second movement – with the Nevines we lose ourselves in the ambiences, whereas the Jade Quartet doesn’t relinquish its tight grip on our sensibilities, heightening the sense of unease and shadows that are unresolved. The violin’s “voice from the gloom” stimulates other voices to follow, then leads the way out when the tensions reach disturbing levels, allowing the angst to gradually ebb away – incredible playing in both versions!

The third movement’s Allegro Pesante has more incisive, razor-sharp attack from the Jade Quartet, almost unrelenting in its penetrative persistence, contrasting the “slow waltz” aspect of the Trio all the more with the soulful melancholy of its lines, as does the return of the biting opening reacquaint us with its fearful obsessive manner. Both performances vividly characterise the finale’s juxtapositioning of its Misterioso opening with a driving allegro molto, the music’s sharply contrasting moods reflecting the extent of variation exhibited in human behaviour, an anomaly suggested by the dissonance of the work’s final chord.

Moving our time machine’s dial forward once again we encounter Ritchie’s String Quartet No, 3, not inappropriately subtitled “In Time”, and composed specifically for the Jade Quartet in 2023. Its programme is ostensibly an oblique commentary on the stages of human life in general term, the movements “framed” by a First Dance and a Last Dance, and sporting pensive titles such as Heartbeat, Perpetual Motion and Funeral March, each bearing associated “mortal coil” confluences.

First Dance is vibrant and changeable, good-humoured and acerbic, essentially interactive, and expressing joy in its sharing – a marked contrast with Heartbeat, where everything is subjected to the “steady beat of time”, the responses to the plucked rhythms occasionally “out of synch”, suggesting arrhythmia or ectopic beats as part of the human condition. There’s also touches of Haydn’s drollery in places, as with the latter’s “The Clock” Symphony.

Perpetual Motion is something else again, the rhythms angular and anxious, going in and out of both conviction and certainty – the playing builds up wonderfully aggregated trajectories before the music self-reflectedly winds down, a single voice cast adrift – “frei aber einsam” – its solitariness a contrast with that of the following Funeral March, and its intensely communal outpourings of emotion from those still living. After this, Last Dance is something of a surprise, a kind of “is that all there is?” response to the certainty of life’s ending – the music conjures up a determination to vitalise existence with almost folk-fiddle-like movement, energy and life, to the point of obsessiveness and even hints of desperation – but the final gesture is determinedly upbeat and unequivocal!

This is a release to put with two other landmark recordings of string quartets by New Zealand composers that I’ve enjoyed over the years – Anthony Watson’s on a 1994 Continuum CD (CCD1065), and Gareth Farr’s recorded by the Morrison Music Trust on MMT 2019. The new disc of Anthony Ritchie’s trio of quartets from the superb Jade String Quartet has already given me the utmost pleasure, as outlined above – and I look forward to many more rehearings, both here and in concert! Thoroughly recommended!

Wellington City Orchestra at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, with Diedre Irons (piano), Brendan Agnew (conductor), and Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor)

Wellington City Orchestra at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, with Diedre Irons (piano), Brendan Agnew (conductor), and Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor)

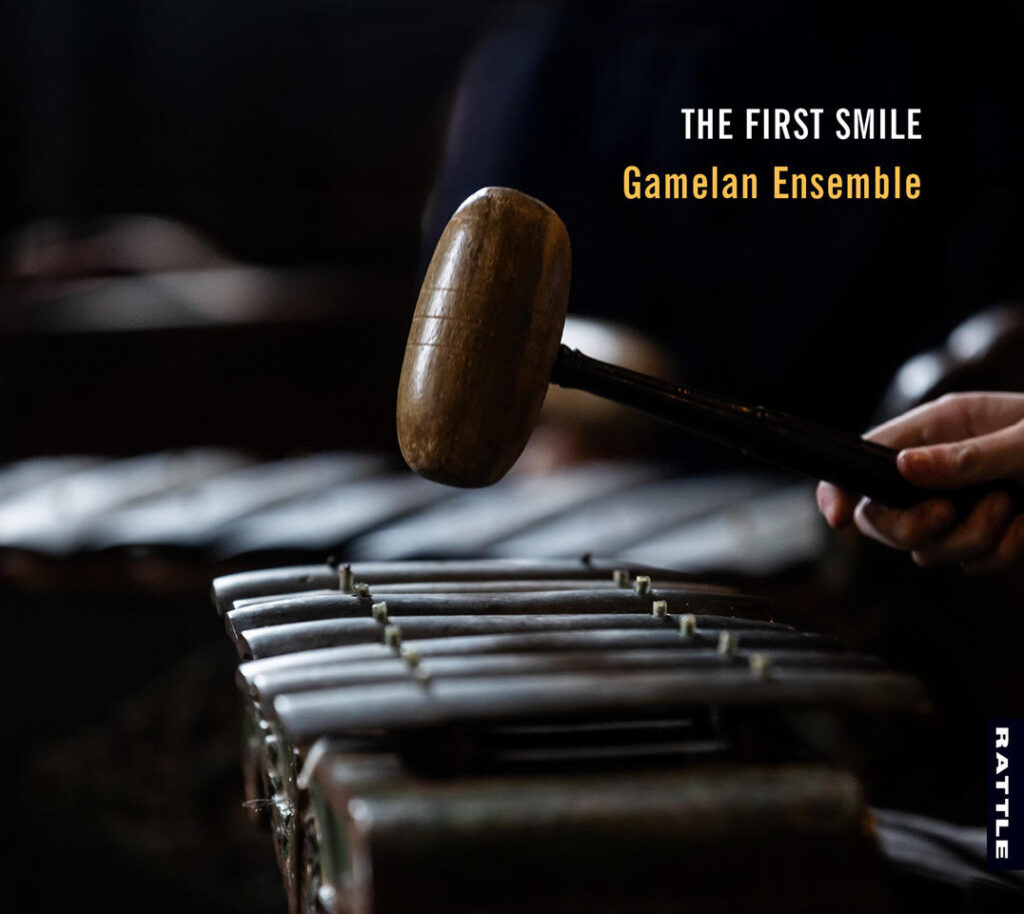

The First Smile | Gamelan Ensemble – Rattle Records (2024)

The First Smile | Gamelan Ensemble – Rattle Records (2024) Allan Thomas – photo by John Casey

Allan Thomas – photo by John Casey Gambang ( xylophone-type instrument, struck with soft beaters, and with wooden keys unlike other bronze-keyed instruments of The First Smile gamelan )

Gambang ( xylophone-type instrument, struck with soft beaters, and with wooden keys unlike other bronze-keyed instruments of The First Smile gamelan ) Saron — bronze keyed instrument struck with wooden beater ( drawing by Barbara Lyon, photo John Casey )

Saron — bronze keyed instrument struck with wooden beater ( drawing by Barbara Lyon, photo John Casey ) Gong (l) Kempul (r) : ( photo John Casey)

Gong (l) Kempul (r) : ( photo John Casey)