SHOSTAKOVICH UNPACKED

New Zealand String Quartet / Ghost Trio

String Quartet No. 4 in D Major Op.83 (1949)

New Zealand String Quartet ; Peter Clark (violin) / Arna Morton (guest violinist)

Gillian Ansell (Viola) / Callum Hall (guest ‘cellist)

Five Pieces for Two Violins and Piano (arr. Lev Atovmian, 1955)

Peter Clark and Monique Lapins (violins) / Gabriela Glapska (piano)

Piano Trio No. 2 in E Minor Op 67 (1943-44)

Ghost Trio: Monique Lapins (violin) / Ken Ichinose (‘cello) / Gabriela Glapska (piano)

With: ROBERT BURCH (1929-2007) – Essay to the Memory of Dmitri Shostakovich for

‘cello and piano (1975) Callum Hall (‘cello) / Gabriela Glapska (piano)

Prefab Hall, Jessie St., Wellington

Wednesday, Ist October 2025

Part of a welcome (and essential) commemoration here in Wellington of the 50th anniversary of the death of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) has been “Shostakovich Unpacked”, a four-part series of concerts exploring some of the composer’s chamber music masterpieces. This was the third concert in the New Zealand String Quartet’s series which presents five of the composer’s fifteen string quartets along with various other chamber works from similar periods in Shostakovich’s creative life, much of which met by official disapproval, and for a time in the form of censure from no less threatening a figure than the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin.

I couldn’t make it to the two earlier concerts in the series; and after listening to the ensemble’s superbly-wrought reading of Shostakovich’s Fourth Quartet found myself wishing I had moved more sizeable portions of heaven and earth to try and do so! Still, gratitude for what one has and can do is a marvellous thing on its own terms – and the music-making in this evening’s concert was of an order that one was left to marvel at in astonishment! And, it was little short of luxury casting to have TWO ensembles of such quality performing in the same programme, with the added bonus of items featuring members of each group displaying as much enjoyment in the collaborations as the skills required to successfully bring them off.

I particularly enjoyed the contributions made by the two “guest” players in the NZSQ, each notable for their “blending into” the overall textures as for their individual voices, always alive to the potentialities of each phrase they articulated. Arna Morton’s violin sturdily and ambiently partnered leader Peter Clark’s instrument throughout the folksy first movement, while taking her instrument’s mosaic-like opportunities throughout the rest of the work with great surety. Callum Hall’s ‘cello had more opportunities for its solo voice to shine, repeatedly catching the ear with both rhythmic and lyrical enactments of resounding character. Both players seemed for the occasion a glove-like fit into the ensemble’s realisation of a work from a composer whose personal expressions of ideological belief frequently collided with censorious officialdom at the highest (and potentially deadliest) level.

Shostakovich wrote this quartet on a “high” after having attended as an official Soviet spokesman (amazingly, at the directive of Stalin himself) the “Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace” held in New York in March of 1949. Stalin also revoked a previous (1948) ban on the music of “formalist composers” in order to cast the visit of his “representative” to the US in a more positive light. Obviously emboldened by this, Shostakovich had straightaway begun work on the quartet on returning home in April, and finished it before the year was out. Five months later, after intense rehearsals and soul-searchings, the work was privately performed by the composer’s favourite Quartet, the Beethoven Quartet, to an invited audience, whose members immediately expressed alarm at the new work’s ostensible use of Jewish musical idioms. The upshot was that Shostakovich was persuaded to withhold the first public performance and wait “for better times” – which came with the death of Stalin in 1953, and the work’s premiere in December of that year. By this time, the composer’s cynicism at the “new era” was apparent, writing to a friend, “The times are new, but the informers are old”.

All of this history seemed of little concern as the work’s heartwarming introductory sounds were initially launched by the players – a lovely lyrical ambience whose trajectories first suggested something exotically folkish, almost bagpipe-like, with the droning lines of viola and ‘cello underpinning the rhapsodical outpourings of the two violins – tensions arose between the increasingly insistent, sometimes dissonant voices, before shifting harmonies brought viola and ‘cello into the discourse – a more sombre minor-key shift brings meanderings, a hint of a dance and a brief return to drone-accompanied lyricism at the movement’s end. The Andantino’s first 4-note phrase on the violin straightaway had me thinking “Tchaikovsky”, but not the rest, an intensely-wrought waltz with the ‘cello silent until the player reintroduced the same “Tchaikovsky” theme – the intensities rose and fell, with Peter Clark’s violin sounding a beautifully “covered” tone replicated by his companions, and falling gradually away to echoed remembrances of what had gone before.

A gorgeously “chugging” figure introduced the Allegretto, Callum Hall’s ‘cello leading off with a workmanlike theme repeated by the violin, followed by a whimsical unison “trio” of violin viola and ‘cello, the ambience being of a ghostly kind of “night ride” that was then cranked up by the violin’s Jog-trot rhythms (Shostakovich paid a visit by Rossini?) and with wind-blown chromatic figurations introducing an eerie aspect to the journey. Where it eventually took us was to somewhere akin to Robert Schumann’s renowned “other realms” description of worlds of hitherto unexplored experience, a state of being often requiring courage and steadfastness for both performer and listener. Here Gillian Ansell’s viola was the ideal fulcrum for such action, a voice in the midst of the void inviting others to plunge with her into the throes of one of the composer’s most challenging, and in the circumstances, reckless undertakings.

With several audaciously delivered pizzicato chords the introduction to the finale revealed its creator’s raison d’etre for the work, which gradually built up from its robust, truculent beginnings into a kind of danse macabre drawn from Jewish-sounding dance motifs, an unbridled and unashamedly grotesque outpouring of lament in a similar vein to that sounded by the composer’s Second Piano Trio finale. It was no wonder that the work’s first private audience was disturbed at Shostakovich’s apparent insensibility to potential strife and condemnation with this music – its scale was almost orchestral in places, with powerful unisons, sharp accents, and massive chordings, all of which eventually unravelled to leave mere vestiges of desolation for us to marvel over at the music’s end.

Not in the above written order, the programme’s next item was, appropriately enough, a work written in 1975 by a little-known but still significant New Zealand composer, Robert Burch, as “An Essay to the Memory of Dmitri Shostakovich, for ‘cello and piano”, performed by Callum Hall and Gabriela Glapska, one introduced and preluded by Peter Clark, who read an additional posthumous word-tribute by Burch to his illustrious fellow-composer.

Much of the work was not inappropriately sombre, beginning with heavy introductory unison notes from both instruments, stern exchanges, either in unison between piano and ‘cello or in counterpoint with one another. The mood remained serious and studious at first, occasionally highlighting a particular rhythmic five-single-note figure on both instruments – a passage with the cello played pizzicato followed, as did afterwards an almost ad lib section, the cellist bouncing the bow on the instrument’s strings by way of advancing the theme in a different form. The piano suddenly embarked on a convoluted, rhythmically rugged expansion of the thematic material before taking up a fugue-like passage which the cello interrupted, again with the abrupt five-note passage. After a series of forceful chords from the piano, the instruments seem to enter into some kind of collusion, the ‘cello sounding long-breathed lines and Elgar-like pizzicato chordings, to which the piano replied with gently luminous harmonies in the higher registers, the cello continuing to draw out the five-note patternings in more contentedly-expressed terms of acceptance of the piano’s celestial-sounding representations.

In view of Shostakovich’s well-documented sense of somewhat ironic humour, it was appropriate to have some musical representation of his facility in this respect, with ample proof furnished by a performance of several pieces arranged for two violins and piano drawn from the composer’s various suites of “lighter” music for film and other “incidental music” activities. One of his composer-friends, Lev Atovmian, was frequently assigned by Shostakovich to produce arrangements from several of his stage and film scores, one of which was the collection Five Pieces for Two Violins and Piano. I must admit to enjoying looking further into the individual pieces’ genesis (at the risk of further elongating this review!) – the opening Prelude was from the 1955 film score The Gadfly, a mixture of tenderness and ebullience which the players designated with considerable relish. Then came the Gavotte, lovely and “bouncy”, from incidental music to The Human Comedy (1934), and followed by a poignant Elegy from the same work, a sequence originally titled The Panorama of Paris. The succeeding Waltz, supposedly from music for a cartoon film The Tale of the Priest and his servant Balda moved by turns through tense, insinuating and buoyant sequences involving a pompous priest, his beautiful daughter and a resourceful servant – however, the concluding Polka certainly added to its interest with further clarification as to the source – taken from the Ballet The Limpid Stream, its full title was Dance of the Milkmaid and the Tractor Driver. (Surely no commentator would pass on an opportunity for such a colourful mention!)

It almost goes without saying that violinists Peter Clark and Monique Lapins, together with pianist Gabriela Glapska, all readily brought out the fun, the quirkiness and the tongue-in-cheek sentimentality of these pieces, making the presentations as much fun to watch as to listen to. Other qualities far removed from such innocent enjoyments, and ironically involving two of the same performers here, then took over the final part of the programme. This marked the appearance of the “other” ensemble, the Ghost Trio, in which Monique Lapins and Gabriela Glapska were joined by ‘cellist Ken Ichinose for a performance of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Trio, one of the composer’s defining statements concerning, in Gabriela Glapska’s own moving notes about the music, “both intimate grief and the collective trauma of a war-torn nation”.

It was my privilege to have heard the same Ghost Trio play this work less than six weeks ago, at a concert at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, to simply overwhelming effect on that occasion – https://middle-c.org/2025/08/ghost-trios-st-andrews-concert-haunts-the-memory/ – I don’t propose to try and describe the music all over again, merely to report on the effect I thought the work and its performance had on a different audience. When experiencing the work alongside other music by Shostakovich I felt it made a different kind of impact for me, its “shock effect” no longer as marked, but when performed in the wake of something like the Quartet, having a deeper, more lasting sense of unease at the enormity and insidious power of the forces that were obviously arrayed all about the composer’s world in order to keep in place a status quo of power and control – in this case characterised by fear and terror enacted upon any refusing to co-operate. I thought the St.Andrew’s acoustic more responsive to the music as well, where every sliver of impulse seemed to send shock waves in all directions – the ambiences of the Prefab Hall made, I thought, the work’s impact a tad more diffuse, though a second hearing can easily produce variants, musicians being human beings. Though, in short, less of a “knockout” performance for me this time round, the Trio further intensified my awe and respect for the composer in this music and for the people who put themselves “on the line” to bring these works off with such searing commitment!

As did the rest of the programme – a great success for all concerned!

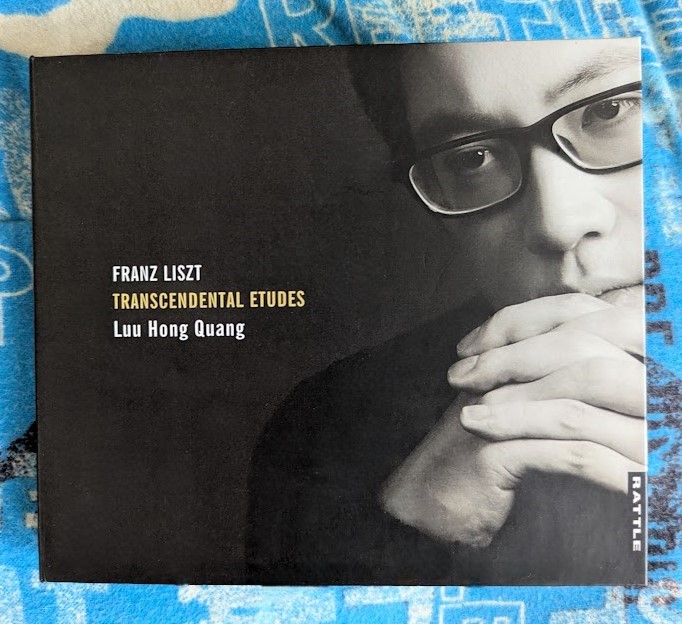

Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu Quang Hong Luu

Quang Hong Luu

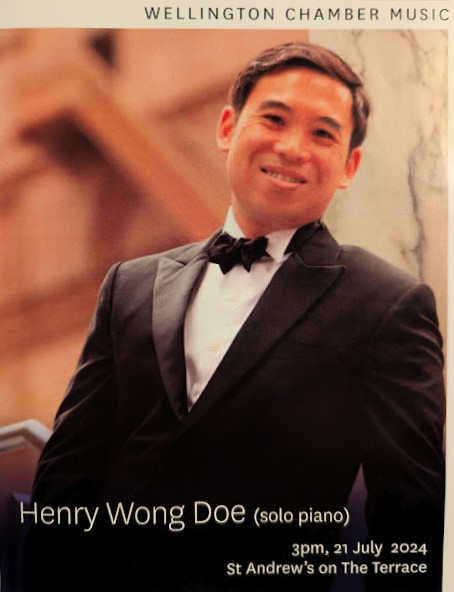

Wellington Chamber Music presents :

Wellington Chamber Music presents : Orchestra Wellington Music Director, Marc Taddei – photo credit: Latitude Creative

Orchestra Wellington Music Director, Marc Taddei – photo credit: Latitude Creative Somi Kim, piano, plays Germaine Tailleferre’s 1924 Piano Concerto with Orchestra Wellington – photo credit: Latitude Creative

Somi Kim, piano, plays Germaine Tailleferre’s 1924 Piano Concerto with Orchestra Wellington – photo credit: Latitude Creative Soloists Emma Pearson (soprano), Margaret Medlyn, (mezzo-soprano), Emmanuel Fonoti-Fuimaono (tenor) and Robert Tucker (baritone), with the Orpheus Choir of Wellington, Orchestra Wellington, and Music Director Marc Taddei – Photo credit: Latitude Creative

Soloists Emma Pearson (soprano), Margaret Medlyn, (mezzo-soprano), Emmanuel Fonoti-Fuimaono (tenor) and Robert Tucker (baritone), with the Orpheus Choir of Wellington, Orchestra Wellington, and Music Director Marc Taddei – Photo credit: Latitude Creative