Marc Taddei and Orchestra Wellington – Photo: Andrew Best

Marc Taddei and Orchestra Wellington – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington presents:

SECRETS

WILLIAM PHILIPSON – House of the Faun

with Arohanui Strings

Lior Balachness – conductor

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART – Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat Major K. 364

with Benjamin Baker – violin

Yura Lee – viola

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH – Symphony No. 4 in C Minor Op.43

Marc Taddei – Music Director

Orchestra Wellington

Michael Fowler Centre,

Wellington

Saturday, 20th September, 2025

This, the fourth concert in Orchestra Wellington’s 2025 season will go down in my memory as one of the most remarkable! Everything about it seemed from the outside like a collection of interestingly vivid but disparate ideas. These had chronological “through-lines” of their own, but however “connected” with previous and future happenings they seemed almost totally unrelated to one another as part of a single evening’s music-making. And yet, despite such seeming “randomness” there was, from the opening item onwards, some over-riding synergising force , coded liasoning routine or archetypally-understood aspect which either dissolved or flowed over, through or around all impediments, and, against all odds, sculpted out from the music an impression that nothing was impossible, ill-fitting, awkward or cross-purposed which couldn’t be put to rights or made to work if the spirit was willing, resourceful and determined!

Classical music concerts have in the more recent past been mostly streamlined, well-organised, uninterrupted, stylised, moderated, time-honoured events whose success nearly always depended on a certain degree of homogeneity in terms of presentation relating to style, content, repertoire and performance standard. All of these things have been features of Marc Taddei’s successful tenure as Music Director of Orchestra Wellington, but his ever-increasing readiness to interact with his orchestra’s “community”, has established and enabled a wider homogeneity with local musicians, composers and music educators who make up the fabric of musical life in the capital.

An ongoing relationship with such a group has been with the ever-delighting and tantalising Arohanui Strings’ group, whose students of all ages have often participated in the Orchestra’s concerts, as was the case this evening. The programme prioritised the group’s involvement by beginning with a work from William Philipson, a 2025 SOUNZ commission for Orchestra and Sistema Youth Orchestra, “House of the Faun”, one inspired by Philipson’s visit to the ruins of Pompeii, Italy, where remnants of a famed “House” were excavated, many centuries after the Mt Vesuvius eruption. Distracted as I was by talking with various people nearby and watching the stage comings-and-goings, I didn’t get to read the composer’s descriptive programme notes, before the Arohanui Strings’ conductor Lior Balachness was on the podium, and, with the older Arohanui students sitting in front of the Orchestra, ready to begin the piece!

Opening impressively. with arresting percussion-primed introductory chords, firstly with strings and then winds and brass, the music set us amongst ambiently rolled-out sound-pictures featuring languid winds, gradually nourished by strings and then reinforced by the brass and percussion – osmotic scenes of slow, but momentous waves breaking and washing over gorgeously-sculpted beachscapes. It all seemed to unfold of its own accord, thus suggesting an ancient, even timeless kind of process, though with the subsequent crescendi levels approaching the seismic in both volume and monumentability – occasionally a solo instrument characterised an individual detail (I noted a solo cello at one point and a solo violin at another) – but though the human element was briefly represented, it was the music’s Ozymandias-like implacability that stayed in the memory, tending to dwarf such detailings as faun statues, mosaic floorings and Doric columns, all muted in the face of nature’s disdain for these past glories.

All the while I thought the playing a well-nigh indissoluble match for the music – but once “The House of Faun” had sounded and then relinquished its spell, we were then given a demonstration of the group’s abilities with a “classic” – in this case a strings-dominated version of Tchaikovsky’s “Russian Dance” from the evergreen “Nutcracker” Suite, bringing forth more of the same appreciative audience response.

Next, we were charmed by the entrance of the even younger Arohanui players, mostly with their violins, though I noticed a single horn-player, not much bigger than the instrument she (I think) carried, but possessing rhythmic skills proving of inestimable value to the proceedings! I actually didn’t know the first tune the group presented, but the horn-player kept the piece’s trajectories on the rails with penetrative notes inserted in the right places each time round. I knew “What shall we do with a drunken sailor?”, which bounced along in fine style, but the best came with “Tutira mai nga iwi”, with which we were encouraged to join in ( with all those years of “Music in Schools” doing the trick here, nicely! – I even heard the occasional “Aue!” from some of the audience!).

During the performance stage’s rearrangement after the youngsters’ departure, Marc Taddei introduced the orchestra’a 2026 programme, “Collaborations”, giving nothing away except a general idea involving partnership “with (to quote the maestro himself) as many extraordinary individuals, ensembles, choirs, dancers and composers as we can”! So, with that tantalising glimpse into the oncoming musical year with Orchestra Wellington, we were then able to settle down to enjoy the next item on this evening’s multifaceted programme – Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s adorable Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat, for violin, viola and orchestra, K.364.

I had seen and heard Kiwi Ben Baker play before, but Yura Lee was a name new to me. Korean-born, and currently Los Angeles-based, she had begun her musical career as a violinist but was attracted to the viola because of the instrument’s frequent exploration of a deeper range of internal harmonies and sonorities than the violin afforded – so she’s now a virtuoso on both instruments, here taking the viola’s part. The rapport between the two musicians made tonight’s performance one I shan’t leave behind for a long time!

From the beginning, the soloists played with the orchestra, creating a kind of visually “integrated” feeling about what the players were doing with this music, advancing musical rather than display-centred attitudes about the work, and, of course, giving that opening tutti an enhanced richness and sonority, especially the “Mannheim crescendo-like” buildup to those wonderfully “tone-drenched” repeated notes at its climax – a simply marvellous moment! Then, when the soloists came in, their sounds simply grew out of the textures in a most naturally-evolving fashion.

Together Baker and Lee as much “danced” as “conversed” their exchanges, in places with almost “Astaire and Rogers” accord, their interactions feeding the growing excitement which then broke out so joyously at the first big orchestral tutti in terms of pleasure and delight, underlining the minor-key seriousness of the development all the more, as well as the relief of the lines being able to come together again for the opening’s brief recapitulation. The same infectious orchestral energies highlighted the playfulness of the cadenza’s “anything you can do” exchanges and the satisfactions evinced by the orchestra’s concluding measures.

We could hear from this work’s slow movement something of the composer’s grief at his mother’s unexpected death the previous year , all poignantly shaped by conductor and orchestra at the beginning, with the occasional emphasis on certain notes tugging at the heartstrings. Baker and Lee intertwined their utterances mellifluously, giving an impression of one voice “listening” to another before replying, with perhaps the most heart-stopping moments to be found in the shared cadenza, where the two voices mirrored each other’s tones at once in accord and yet so distinctively.

After this the finale was pure release! – light and quick and playful, with characterful interchange suggesting ongoing rather than conclusive utterances! Baker and Lee make it all music of response and interaction rather than anything striving for effect – each player’s concluding flourish feels like an invitation to the other to share rather than a declaration of independence! It all produced a great and demonstrative ovation at the end for all concerned.

And so to the Shostakovich Symphony, the work which had to wait for twenty-five years after its completion before being performed. The composer had finished the work in 1936 for its premiere with the Leningrad Philharmonic, and rehearsals were actually under way, when suddenly the scheduled performance was abandoned. Accounts differ as to why this actually happened, but the consensus has adjudged the work was withdrawn because of pressure exerted by the authorities in the wake of the “Muddle instead of Music” attack on Shostakovich’s opera “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District” made by Stalin and his Pravda minions earlier that year.

Orchestra Wellington Strings play Shostakovich – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington Strings play Shostakovich – Photo: Andrew Best

Though the full score of the abandoned symphony was lost during the war a complete set of orchestral parts were found and the score was reconstructed. But though this was some time after Stalin’s death it was not until December of 1961 that the Fourth Symphony received its actual premiere in Moscow, with Kyril Kondrashin conducting. When the composer was later asked whether his later work would have been more like the abandoned symphony had the latter been played and accepted in the 1930s, he replied, “I would have displayed more brilliance, used more sarcasm, I could have revealed my ideas openly instead of having to resort to camouflage; I would have written more pure music….” And then he added, “But I am not ashamed of what I have written – I like all my compositions.”

Though not a New Zealand premiere, the work by dint of its rarity in performance still generated some interest and excitement akin to a landmark event in Wellington’s musical life. It might be apposite to mention here that, tenuous though the connection might have been, the composer himself was not unaware of interest in his music in this part of the world – when in 2008 I interviewed the wonderful Invercargill-born pianist Janetta McStay towards the end of her long and fruitful life she told me that, late in 1957, upon hearing about a particular new work of Shostakovich’s and making an enquiry she was eventually sent a copy of the score of his recently-written Second Piano Concerto from the Russian firm who published his music – and included in the package was a little note of thanks from Shostakovich himself concerning her interest in his music – she soon afterwards gave the New Zealand premiere of the work!

Though its own premiere took place shortly after the new Piano Concerto’s composition the Fourth Symphony’s music, written fifteen years earlier, couldn’t be more different – by turns epic and ironic, grandiose and volatile, harrowing and playful, desolate and garrulous. Its size (over an hour), its instrumental proportions (normally over a hundred players, with more strings than Orchestra Wellington could muster on this occasion) its gargantuan formal structurings (sonata forms of outsize proportions) and its incredible profusion of thematic ideas (both outer movements are mini-epics in themselves!) seemed to ally Shostakovich with Mahler as a symphonist, as did ear-tickling moments like the cuckoo calls in the first movement, the ironic second movement’s dance-like rhythms, recalling the scherzo from the older composer’s “Resurrection” Symphony, and the funeral march that begins the third movement, drawing from the older composer’s own death-marches from his First and Fifth Symphonies.

Orchestra Wellington winds – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington winds – Photo: Andrew Best

I need to state unequivocally that, in giving this music its best possible chance to “speak”, Marc Taddei and his Orchestra Wellington players sensationally performed miracles! I wrote some observations down as best I could while things unfolded in spectacular fashion! – to begin with, the opening had incredible impact, with winds and brasses striding out firmly and purposefully, followed by the strings’ and winds’ suggestively furtive handling of their subsequent polyphonies, then coming together with the brasses to create a textural panoply that astonished as much with its vigour and confidence as in its sense of knowing where it was going! The winds did brilliantly with their triplet overlays and warning-sounding chorales, but the ensuing orchestral crescendi that grew out of the string murmurings were not to be denied! To the rescue came the bassoon, as it would do repeatedly throughout the work, with empathetic support from the harps (such a feast of texture, timbre and colour! – and wot larks were enacted between perky strings and poisonous sounding brasses at one point!) Sterling tuba and trombone warnings were ignored by similarly vociferous winds, who simply wanted a good romp, despite the brass raspberries that came their way. And then the strings once again! – playing well above their weight, at Marc Taddei’s bidding they dashed into the insanely frenetic fugato that rippled through the ranks – incredible stuff! The brasses couldn’t resist, and neither could the percussion! What a furore! The strings stepped away and into a nebulous realm out of which timpani and orchestra came swinging with huge roars – away went the winds, climbing onto the backs of the double basses and swinging away down the symphonic road, but coming suddenly to three wise sages, a cor anglais, a solo violin and a bassoon (with a double!), each of whom gave his/her own version of “sensible advice” of the “take a break” variety – so they/we did, and so it proved, the cor anglais double-checking with us, just to make sure!

Came the middle movement – moderato con moto – a droll four-note theme was our companion, first with the strings, then the winds and then the brass and timpani – a wistful second theme (strings again) was augmented by lovely horn-playing, before the winds decided to have some raucous fun until being told off by the timpani. The strings just couldn’t resist some fugal play, capricious but easy on the ear – “we can do that too!” intoned the winds, then deliberately playing atonal lines just to annoy others, until the brass brought things back into line by interrupting with the second theme, more martial than wistful, which fired everybody up! – suddenly, it was if as if a skeletal apparition had appeared, dancing to the tune, grinning spectrally and – vanishing!

Orchestra Wellington horns and percussion – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington horns and percussion – Photo: Andrew Best

There was something undeniably Mahlerian about the finale’s opening, the portentous tread of footsteps and the plaintive cries of the winds all combining to produce a funereal atmosphere which some icy string chords helped along – the textures piled up splendidly as the brass and percussion joined the march – some echt-Shostakovich string textures were evocatively floated, and the winds contributed a mournful cantilena – as the winds intensified the line the strings jumped in with two-note phrases that suddenly became urgent and thrustful with the brass’s help – suddenly all was turmoil with wailing winds seemingly trapped with the strings in a kind of sound-vortex, becoming a vigorous tattoo with brass and timpani joining in, then subsiding – but what was this? Was the circus coming to town? Who were these knockabout figures? Extraordinary! What was happening to this music? Shostakovich suddenly introduced a kind of commedia dell’arte scene into which all kinds of characters made an appearance – whimsical playing from the many solo instrumentalists all of whom covered themselves with glory – such lovely swooning string-playing at one point, immediately followed by some kind of comic-turn, the instruments contributing all kinds of show-time star-turns! – and then it seemed, almost without warning, to melt into thin air, as if it never was – until out of the silences strode the timpani, repeatedly leading a tumultuous orchestral onslaught capped by the brasses and percussion. (Was it something Shostakovich obviously needed to get out of his system?) – Here in the Michael Fowler Centre I had never before heard quite such an orchestral tumult! – the aftermath was as if the cosmos had been somehow cleft in twain and left in tatters with only a few pitiless wind chords, a lone trumpeter-sentinel of the watch, and a gently weeping celeste left, the latter leaving us with a single, if equivocally ascending note.

To have made this symphonic journey anywhere would have been a profound experience – but to have been taken on such a one with such music brought to life by conducting and playing as we experienced here was to have been given something well-nigh unforgettable in cherish! Resounding kudos to Marc Taddei and his intrepid players for what I shall long continue to call a “sensational’ musical experience.

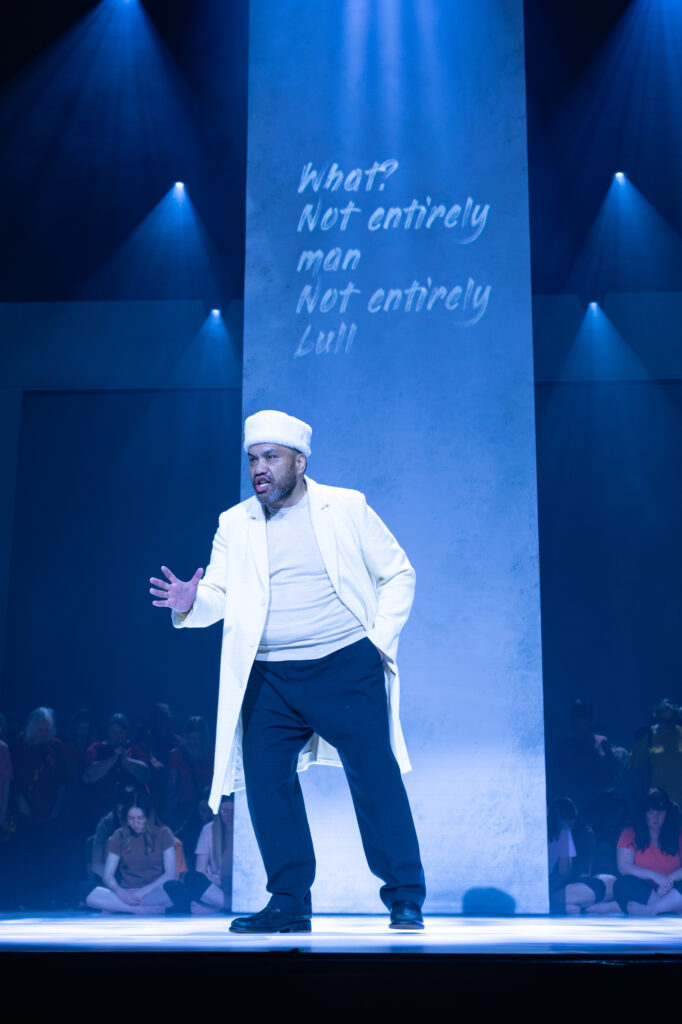

Ipu Laga’aia as Theseus, Sarah Castle as his Mother, and Joel Amosa as Daedalus with some of the community chorus participants – photo, Emma Brittenden

Ipu Laga’aia as Theseus, Sarah Castle as his Mother, and Joel Amosa as Daedalus with some of the community chorus participants – photo, Emma Brittenden Maaka Pohatu as Minos, King of Crete – photo, Emma Brittenden

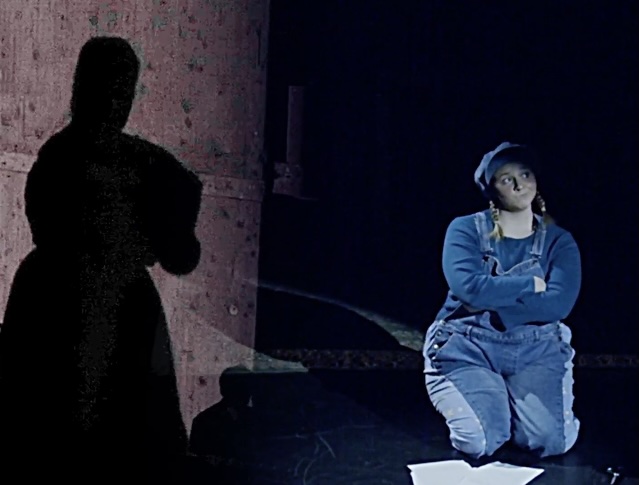

Maaka Pohatu as Minos, King of Crete – photo, Emma Brittenden Community chorus participants in “Monster in the Maze” – photo, Emma Brittenden

Community chorus participants in “Monster in the Maze” – photo, Emma Brittenden

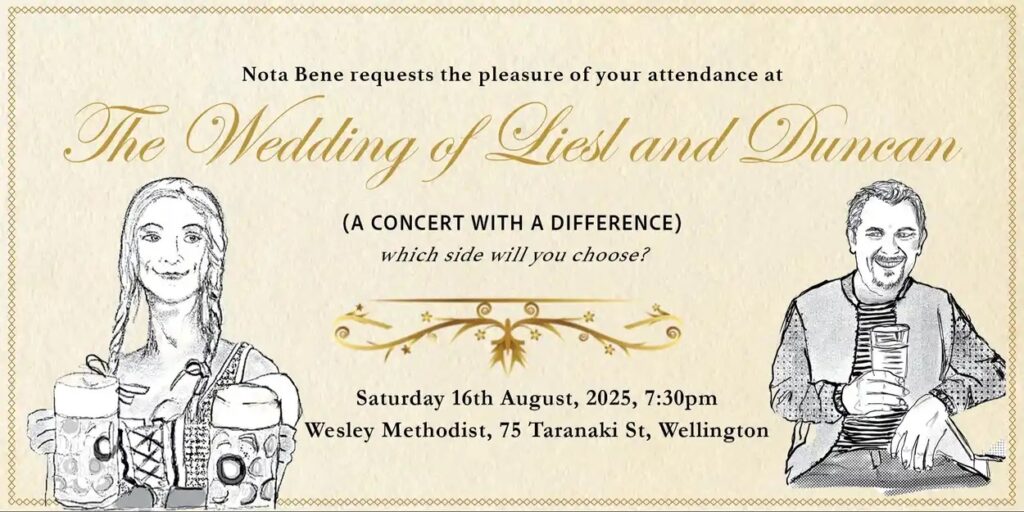

Wellington Chamber Music presents:

Wellington Chamber Music presents:

Julien Van Mellearts (Renato) and Jared Holt (King Gustavo)

Julien Van Mellearts (Renato) and Jared Holt (King Gustavo) Natasha Te Rupe Wilson (Oscar) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Natasha Te Rupe Wilson (Oscar) – photo, Stephen A’Court Madeleine Pierard (Amelia) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Madeleine Pierard (Amelia) – photo, Stephen A’Court