Witch Theatre Productions presents:

Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812

– Music and lyrics by Dave Malloy

Cast: Lane Corby (Natasha), William Duignan (Pierre), Áine Gallagher (Sonya), Frankie Leota (Marya), Jade Merematira (Hélène), Glen Horsfall (Andrey/Prince Nikolai), Henry Ashby (Anatole Kuragin), Princess Mary (Rachel McSweeney), Kevin Orlando (Dolokhov), Patrick Jennings (Balaga) Jackson Cordery (Rope Aerialist):

Chorus: Adriana Calabrese, Tess Lavanda, Kirsty Huszka, Mackenzie Htay, Raureti Ormond, Finlay Morris

Music Director – Haydn Taylor/ Stage Director(s) – Maya Handa Naff, Nick Lerew /

Choreographer(s) – Emily McDermott, Greta Casey-Solly / Set and Technical Design – Joshua Tucker-Emerson / Producer and Costume Designer – Ben Tucker-Emerson

Sound – Oliver Devlin / Alex Fisher – Lighting / Vanessa Woodward – Stage Manager and Props / Charlotte Potts – Ticketing and Audience Experience Manager.

Hannah Playhouse, Wellington

Tuesday 30th April 2024

“What straightaway grabbed me was our vortex-like transition from foyer to auditorium at the Hannah Playhouse earlier tonight, vertiginously drawing us into what seemed like a different world – a journey which then never let up in its exertion of fascination and wonderment upon both mind and body. It was total immersion into “other” realms, to which I unhesitatingly gave myself for the next two-and-a-half hours!”

In the cold, grey light of dawn I’ve quoted myself above, a fleeting impression I managed to scribble down before exhaustion overtook me upon reaching home from my evening’s adventure at Wellington’s Hannah Playhouse last night. I had been at the tender mercies of Witch Music Theatre’s totally compelling production of “Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812”, an adaptation for the musical stage by the composer/lyricist Dave Malloy of Part Eight of Leo Tolstoy’s great 1869 novel War and Peace – seventy pages of searing emotional intensity expressed here in unreservedly straight-from-the-shoulder dramatic and musical terms!

Dominating the Playhouse’s stage precincts (via designer Joshua Tucker-Emerson’s hypnotically flowing cascading-tongues series of platforms) were seventeen singers-cum-dancers (plus a heart-in-the-mouth rope aerialist) who made both the teemingly populous and more intimate vistas of the story very much their own. Their individual characters flourished under the visionary direction of Maya Handa-Naff and Nick Lerew, and were beautifully and atmospherically elaborated by choreographers Emily McDermott and Greta Casey-Solly.

Throughout, singers and dancers combined with twelve on-and-offstage musicians directed from a centre-stage piano by music director Hayden Taylor to bring this fragment of a famous story to heartfelt and pulsating life, which was done with great instrumental elan at certain memorable moments. While the music’s pulsatings occasionally pushed the decibel levels into saturation point, the lines of the voices, both individual and concerted were never seriously obscured, with the diction from the singers remarkably clear in all but the most full-blooded passages – a tribute both to performers and the skills of the sound designer, Oliver Devlin.

Alex Fisher’s atmospheric lighting designs brought out the many variations of intensity required by the stage action, reaching a kind of apex with the appearance of the title’s Great Comet at the end of the story, but straightaway highlighting the characters’ various period costumes (designed by Ben Tucker-Emerson) with appropriately pleasing visual significance, with those of the dancers also relishing their characterful variants to whimsical effect.

How to single out so many compelling individual performances? Of course the show’s relatively intertwined musical textures allied to the similarly close-knit physical proximities of the cast on-stage made for an essentially ensembled production, one to which everybody responded magnificently, to the point where all the characters seemed, in Omar Khayyam’s somewhat bowdlerised words, “to come and go, like players in a magic-shadow show”. Whether alone or ensembled, all played their parts to a kind of perfection.

Of the titular roles, both Lane Corby’s Natasha and William Duignan’s Pierre negotiated their respective characters’ journeyings through their various travails with, in places, heartfelt, almost painful self-realisation, each in ways that expressed their essential personalities – Natasha’s spontaneity and impulsiveness, leading her to trouble, guilt and shame in the affair with the dissolute Anatole Kuragin, was eventually run together with Pierre’s own journey through disillusionment to hope in a better life through love, hence their mutually heartwarming and vocally reflective “understanding” at the end of the work.

Áine Gallagher’s portrayal of Sonya, Natasha’s cousin emphasised her endlessly patient and selfless regard for her cousin Natasha’s well-being throughout the story, including a full-throated avowal to protect her – stirring stuff! And Frankie Leota’s forthright and principled Marya, Natasha’s godmother, spectacularly and adroitly balanced her disapproval of Natasha’s infatuation over the flashy Anatole with plenty of concern for her young charge’s well-being – a colourful portrait! She was the opposite of Princess Mary Bolkonsky, whose portrayal by Rachel McSweeney touchingly emphasised her well-meaning kindness and propriety; and still more of a contrast with Jade Merematira’s sensual good-time girl portrait of Hélène Kuragin, the disdainful wife of Pierre.

Apart from Pierre, the men included Natasha’s betrothed, Prince Andrei, who left Moscow at the story’s beginning at his father’s wishes, respecting the latter’s objection to his son’s impending marriage. Glenn Horsefall played a soulful Andre on his occasional appearances throughout the story before finally rejecting Natasha in the wake of her dalliance with Anatole. This was in stark contrast to the latter, portrayed with plenty of skin-deep smoulder by Henry Ashby, to splendid effect up until his encounter with an enlightened and vengeful Pierre. The drinking, gambling Dolokhov was given a suitably dissolute air by Kevin Orlando, and teamed up well with Patrick Jennings as “Balaga” the Troika-driver, in his stage- dominating, energetic all-together “troika” rendition, a character who was obviously the life and soul of any party within sleigh-driving distance!

The remaining unnamed characters, sang, danced and INVOLVED their obviously entranced audience throughout, with the production throwing in unexpected delights such as an Aerial Rope performer, (Jackson Cordery) who gave a breathtaking display of agility and skill, as well as, at other times, charming us with his accordion-playing skills. It was all completely in line with the “what’s next” kind of spontaneity and energy the show seemed to continually thrive upon.

I was “blown away” by all of this in a way I didn’t really expect to be, and can thus warm-heartedly recommend the production to anybody who has the merest inkling of the original story (from one of the world’s truly GREAT novels!); or whatever inclination they might have to introduce themselves to and enjoy something of its uniquely compelling characterisations of universal human behaviour.

“Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812” will play at the Hannah Playhouse in Wellington until Saturday 4th May (two performances that day, at 2:00pm and 7:30pm!!)

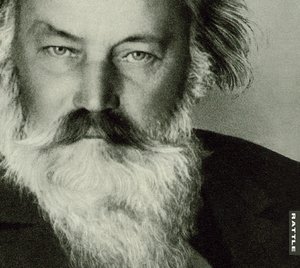

BRAHMS – Complete Intermezzi for solo piano

BRAHMS – Complete Intermezzi for solo piano