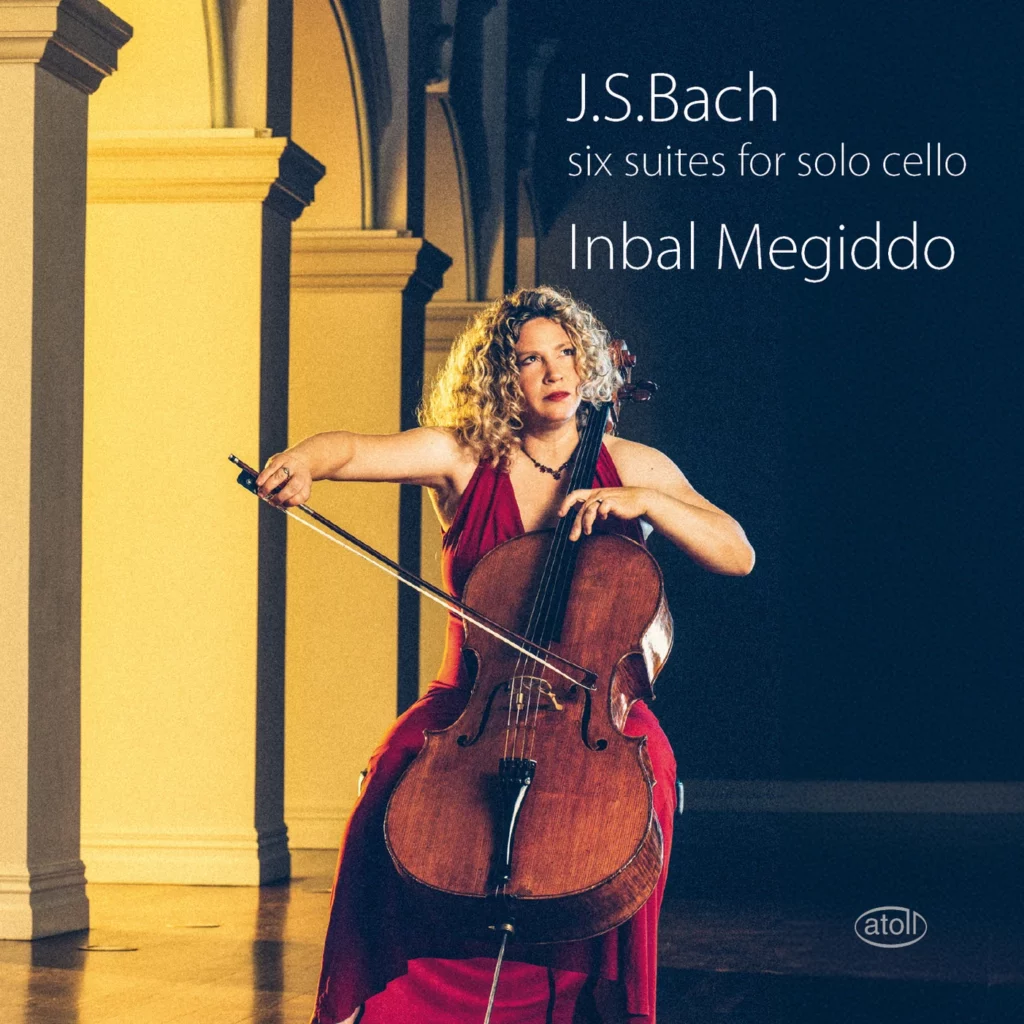

J.S.BACH – The ‘Cello Suites Nos 1-6 BMV 1007-12

Inbal Megiddo (‘cello)

Atoll Records ACD 233

(recorded at Stella Maris Recording Studios,

Seatoun, Wellington)

It took me a little while to approach the Bach ‘Cello Suites as a listener – though I got to know something about the instrument itself soon enough, as it figured prominently in the very first orchestral concert I attended, back in July of 1969. The programme opened with Rossini’s “William Tell” Overture, featuring a solo ‘cellist and the player’s various cohorts introducing that most evocative of musical paintings, a sunrise taking place over the Swiss Alps. It was a sound which seemed to me more “substantial” than the solo violin passages I also got to know at various times, its resonance and depth putting me in mind of the voice of a great actor!

Rossini is a long way from Bach, of course, but I was taking leaps and bounds through music in those younger, more energetic days, mostly with the help of my local Public Library’s classical music LP collection. It seemed only a matter of time before I was within coo-ee of one of the great artistic resurgences of the twentieth century – Pablo Casals’ far-reaching encounter with Bach’s ‘Cello Suites, one which led to the making of an historic set of performances and recordings.

Casals had come across the works in a music shop in Barcelona when still a teenager, had spent the next twelve years studying them, and then presented them in public, usually singly, and programmed with a concerto. Fortunately for us, he then decided to record them, which took place between the years of 1936 and 1939 in both Paris and London. To date the recordings remain unique in terms of an interpreter’s commitment to the music, a realisation one commentator described as “an embodiment of vigour, spirituality and humanity”.

What I vividly recall, upon hearing Casals’ recordings of Bach for the first time was the “earthiness” of the instrument’s sound, largely due, I think, to the player’s own volatile temperament, and his visionary sense of achieving something unique and precious at all costs. More recent interpreters of these works have brought out vastly different characteristics, for example Pierre Fournier’s intuitively seamless flow and refinement, Yo-Yo Ma’s dance-like, spare-sounding lines and tones, and Janos Starker’s simple, unfussy, easily-breathed versions.

Such is the music’s well-nigh endless resource of possibilities, there are now almost any number of recordings to choose from – but it’s a particular pleasure to encounter one made by a musician whose work one knows well in “live performance” contexts. Atoll Records features a complete recording from such a musician, Inbal Megiddo, currently an Associate Professor of ‘Cello at Te Koki New Zealand School of Music in Wellington, and whom I’ve often seen and heard as a concerto soloist and a chamber musician, as well in the role of principal ‘cellist with Orchestra Wellington. Listening to her play these works is to encounter a unique summation of her skills and sensibilities, refracted here through the demands of making some of the world’s greatest music written for the instrument speak its own truths.

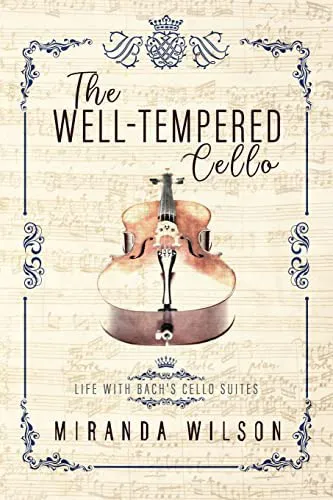

As if pre-ordained my encounter with this recording came after an earlier discovery I’d made of a truly absorbing book about these same works by an ex-Wellingtonian musician, Miranda Wilson, presently living with her family in Moscow, Idaho, USA, while Professor of ‘Cello at the University of Idaho. I was taken by her book right through every single movement of the suites, equating them all as stages in a life relating both to their composer and to her own experience of getting to know and play them. So I was all the more delighted to find Inbal Megiddo, in the booklet accompanying the new Atoll recording, expressing similar kinds of fascinating and thoughtful meditations regarding the suites. I think she sums things up resoundingly when she writes “Bach’s genius lies….in creating music that transcends the limitations of its time and speaks to universal experience, while still allowing each performer’s unique experience to shine through….they (the Suites) are living documents that gain richness through the multiplicity of approaches they inspire….”

Wayne Laird of Atoll Records has crafted a beautiful recording of Megiddo’s traversal of these life-giving works. From the opening Prelude of the G Major Suite there’s a delicious sense of the player delighting in the sounds that flow with such ease, grace and spontaneity – the music’s not unlike the very first Prelude (C Major) from the composer’s “Well-Tempered Clavier, which also has arpeggiated chord progressions, though the ‘cello work occasionally varies the repeatedly-ascending trajectories of the keyboard Prelude. But there’s the same slightly hypnotic sense of “do I wake or sleep?” as the familiar patterns change notes and harmonies, rather like a face subtly but constantly altering its expression – here, Megiddo’s delightfully unforced soundings of the changes seem both impromptu and yet inevitable.

The following Allemande (a French title meaning “German”, incidentally) introduces us to a recurring character of these suites, their affinities with dance forms, not actually accompanying dancers, but suggesting their movements. While Megiddo relishes the ornateness of the spacious melodic lines of this dance, she adroitly marks its turning-points, with Bach giving her lots of rhythmic “help” amid the florid lines, the higher notes decorating and the lower notes marking time, all the while keeping the essential grace of the dance to the fore. She makes the following dance, the Courante, a kind of joyful release with its ready physicality after the Allemande’s decorative elegance, and in even more striking contrast to the slow and stately Sarabande which followed. Bach sometimes used this latter form to heighten moments of great intensity, such as in his St,John and St,Matthew Passions, though Miranda Wilson in her book considered she herself was at first inclined to over-emphasise the piece’s solemnity in performance, largely ignoring its “dance” origins. To my ears Inbal Megiddo sufficiently maintains a terpsichordean feel in the music while still enabling us to enjoy her beautifully filled-out tones, recreating an unselfconscious duality of movement and melody. The concluding movements had no such polarities – the Minuets relished their major /minor key “turns” (the hints of wistfulness in the latter mode a nice touch), while the concluding Gigue draws from Megiddo a truly spirited response whose invigorating effect at a concert any audience might “scarce forbear to cheer”.

Letting the CD play on at first hearing surprised me when the ebullient tones of No.3, the C Major Suite’s grand opening, made an appearance! Upon checking I discovered that Disc One of this set actually contains Suites 1, 3 and 5, simply because it wasn’t possible here to fit all six Suites onto two discs in numerical order (the first three would fit, but not the last three!) Having thus re-aligned my listening expectations and readings of Megiddo’s own commentaries on the music, I was able to happily continue! So in the player’s own words here, No. 3 is “confident, eager and full of optimism”. It requires an extension of technique using the thumb in places which, when first reading Miranda Wilson’s description of “how it’s done” makes it sound fearsomely awkward, though reading on also brings one to a description of the player’s joy when the technique is mastered! Inbal Magiddo’s playing conveys that kind of joy throughout this ebullient piece!

This Allemande is rather more ebullient than that in the opening G Major Suite, and the following Courante has an almost frantic aspect – and it’s one of those pieces in which my obviously susceptible brain finds itself listening to passages as common-time pieces rather than ones in ¾! Fortunately, the Sarabande comes to my rescue, through Megiddo’s steady, though beautifully pliable phrasings, which restore my faith in my own musical responses. After this we are treated to a Bouree, whose common-time straight-forwardness eminently suites this work as a whole – the minor-key section is played more legato, more inwardly and introspectively. But then Megiddo returns wholeheartedly to Bachian ebullience with the final Gigue, especially relishing that brief but spicy double-stopped “droned” sequence with its chromatic two-note exclamatory gesture that I’ve always delighted in hearing.

The Fifth Suite, the last on this disc, breaks a pattern set by the previous two works, as well as the Second and Fourth Suites (on the other disc) – in the first place, the cello is tuned differently, Bach using the technique known as scordatura, which refers to a kind of tuning to achieve a different sound and harmony, in this case two strings tuned to the note G. Another difference is that the Prelude to this Suite isn’t like the others form-wise – this one is more like a Baroque tone-poem, its portentous, ornamented opening leading to a fugue, the composer’s writing adroitly suggesting that new parts continue to enter, and that they keep on moving along, even when not audible – amazing “sleight-of-hand” exhibited here by Megiddo in her all-encompassing figurations. The Allemande here is as slow and weighty as the Prelude, while the Courante, described by one commentator as “lusty” in its robustness maintains the Suite’s somewhat darker, typically C Minor quality. And then. the Saraband suddenly eschews all ornamentation, Megiddo here bringing out the essential loneliness of the traversal – her descriptive words “solitude and contemplation” are more than apposite for this music, particularly in regard to the deepest notes of this meditative journey.

Into the void dances the dark-browed Gavotte, its physicality emphasised by the chunky “blocked” character of the writing, into which Megiddo engagingly throws herself holus-bolus, so that as a listener I myself almost feel as if I’m playing the instrument myself! The contrasting episode is chalk-and cheese, a running, triplet-like flowing, all chunkiness removed or sidelined, and listening in amazement, until its “feistier-than-ever” return. There remains the Gigue, a real ”swinger”, here, more waltz than jig-like to my untutored, even temporarily child-like ears, almost like a parent swinging an ebullient child – did Bach engage in those pastimes, I wonder?

Though I feel as though I’ve written a lot. Megiddo’s playing makes me feel as though I’m “flying” through the music, completely absorbed with it all, and at the halfway point already! Suite No.2 in D Minor, first-up on the second disc featuring “even-numbered” works, remains an extraordinary listening experience in the wake of the first Suite’s relatively carefree romp, beginning with the yearningly long-breathed Prelude, which Megiddo builds with unerring judgement towards the moment when the piece’s first “rest” occurs on an unresolved chord, and the piece seems to think out loud, “what now?” – here, the ‘cellist’s beautifully-circumspect renewal of the music’s D Minor key with five spacious arpeggiated chords seems a perfect resolution. The Allemande is a little mini-adventure on its own, journeying out of and then back into the home key, one which Megiddo seems to have all the time and space in which to do – a journey one wishes would simply go on!

“A mad dash of sixteenth notes” is Miranda Wilson’s recorded opening comment re the Courante, an opinion modified upon her realisation that the piece shares a bassline with the composer’s great Chaconne from the Second Partita for solo violin, one of the all-time “classics” of Bach’s instrumental music. Nevertheless, the oft-used “devil at your heels” description certainly adds spice to the music, and Megiddo’s playing of it heightens the contrast with the Sarabande which follows. This latter movement, extraordinary in its own right, draws an incredible range of intensities here, from the deep solemnity of the opening to the almost operatic expansion of line in the concluding moments of the piece’s second half. Even the Menuet which follows is full-on, it seems, in Megiddo’ s hands, right from the opening, though the major-key of Menuet II is relaxed and charming. And the Gigue here partly surprises and partly fulfils expectations with its forcefully-droning bassline delivering plenty of D Minor intensity!

Inbal Megiddo equates the E-flat ‘Cello Suite (No.4) with increased maturity, as does Miranda Wilson, who states unequivocally that it’s “music for grown-ups”. Part of the increased complexity involves the music’s key of E-flat not corresponding with any of the cello’s open strings, meaning that the player has to “find” or “make” the correct pitch, as well as make many “extended” left-hand positions, while not enjoying the same resonances that an open string would supply. The E-flat key gives the music a wonderful richness at the start, which continues and deepens until the music reaches the cavernous depths of a low C-sharp – almost as if its sounding is of the “Abandon hope all ye who enter here” variety, the music pauses and seems to take stock of elaborating briefly on the excitement of proximity to these extremes before climbing back to the starting-point of the movement. Then, dance movement though it is, I find Megiddo’s playing of the Allemande a fascinating discourse in its own right, filled with inflexion and interest. The livelier Courante, too, thanks to the player’s ever-pliable touch, presents an engaging amalgam of its busy lines; and afterwards, the following Sarabande is, quite simply, a heartfelt expression of warmth of the human spirit.

Continuing in this great-hearted vein is Part I of the Bouree, its five-note ascending motif eagerly driving the piece onwards, alternating with occasional downward-swoops and dance-like phrases – the physicality of Megiddo’s playing exuberantly makes the most of where the momentums carry the lines. Part II of the dance is just as committed, if rather more earthbound with its drone-like underpinnings – but the music takes wing again with the Gigue, which for me Megiddo turns into a high-spirited romp, a kind of “liberating” gesture when set against the solemnity of certain of its earlier movements.

How, then, to put such music against what follows with the Sixth and last of the Suites? Megiddo describes the D Major Suite as “the beyond, the afterlife…..(which) transcends earthly concerns entirely” – while for Miranda Wilson, it’s the Sarabande movement whose simplicity has the most power, a duality of timeless and awareness of mortality in its sublimity. Inbal Megiddo’s comments regarding the five-string ‘cello that Bach supposedly wrote this music for indicate that she too used a five-stringed instrument for this recording of the Suite. Opinions continue to vary among scholars, musicians and commentators regarding the use and efficacy of such an instrument when performing this work – Megiddo’s performance with her chosen instrument seems to me an almost unqualified success, be it the celebratory strains of the Prelude, the quiet authority of the Allemande, the ebullience of the Courante or the intense nobility of the Sarabande.

For me the D Major opening of the Prelude is like no other – it proclaims an ecstatic kind of triumph which combines a bright and welcoming ethos, while using a freer form with more display-like passages that liberates thought and gives emotion wing right across the instrument’s five-string sound-spectrum. I particularly loved Megiddo’s luftpause towards the Prelude’s end, allowing those unresolved chords to resonate into an expectant silence before gently and calmly leading the resolution home.

I was, I admit, taken by surprise by the impetuosity of Megiddo’s playing of both Gavottes, expecting a more “other-worldly” treatment (as might befit the Gods at play in Elysium?) – the easier, somewhat more loping manner of the concluding Gigue more in accordance, I thought, with the player’s description of “a reaching towards heaven” in the music. But is heaven, after all, merely a fulfilment or a transcendence of one’s expectations? Bach’s music here, in Inbal Megiddo’s hands, has taken me further than I expected to go, joyously demonstrating all over again that “known and yet new-found” experience one gets from hearing whole-hearted performances of great music.

The Jade String Quartet: Robert Ashworth (viola), Maranda Adams (violin), Charmian Keay (violiin), James Yoo (‘cello)

The Jade String Quartet: Robert Ashworth (viola), Maranda Adams (violin), Charmian Keay (violiin), James Yoo (‘cello) Wellington City Orchestra at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, with Diedre Irons (piano), Brendan Agnew (conductor), and Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor)

Wellington City Orchestra at St.Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, with Diedre Irons (piano), Brendan Agnew (conductor), and Virginie Pacheco (Assistant Conductor)

Joyce DiDonato sings Berlioz with the NZSO and Gemma New – photo credit Phoebe Tuxford

Joyce DiDonato sings Berlioz with the NZSO and Gemma New – photo credit Phoebe Tuxford Estella Wallace introduces her new work “Of Sorrows” at the Prefab Hall, Wellington’s “Shostakovich Unpacked” – photo: Maeve O’Connell

Estella Wallace introduces her new work “Of Sorrows” at the Prefab Hall, Wellington’s “Shostakovich Unpacked” – photo: Maeve O’Connell Gillian Ansell (viola) and Jian Liu (piano) play Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata – photo: Maeve O’Connell

Gillian Ansell (viola) and Jian Liu (piano) play Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata – photo: Maeve O’Connell