WELLINGTON CITY ORCHESTRA

Justus Rozemond (conductor

with Sophia Acheson (viola )

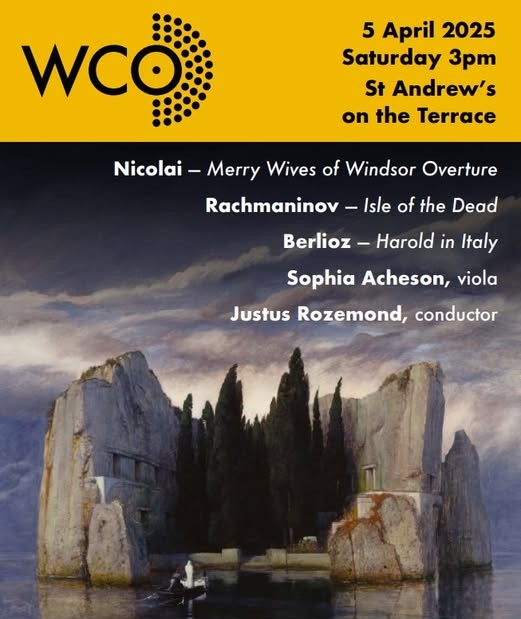

Nicolai – Overture “The Merry Wives of Windsor”

Rachmaninov – Tone-Poem “Isle of the Dead”

Berlioz – “Harold in Italy” – Symphony with Viola obbligato

St,Andrew’s-on-The-Terrace, Wellington

Saturday, 5th April 2025

Concert viewed via video – thanks to Nick Baldwin (camera)

and Angus Webb (editing)

Thanks also to Rowena Cullen (Wellington CO President)

Review for Middle C by Peter Mechen

I’d seen this programme by the Wellington City Orchestra advertised, and was instantly drawn to its boldness, variety and colour, with three works owing nothing to one another but irresistibly drawn together by their very singularity and vividly-wrought panoply of contrasting human emotion. It’s the kind of programming to which orchestras that have a variety of music-directors can bring enterprise and exploration in the form of each maestro’s particular enthusiasms, and whose audiences benefit from such wide-ranging presentations.

So when circumstances conspired against my attending the concert I was delighted to be able to “catch up” with what took place via the kind auspices of Rowena Cullen, the Orchestra committee’s President, through a video of the concert made by Nick Baldwin and Angus Webb, from which I could write a “report” of the proceedings (as I was able to for the orchestra’s final 2024 concert under similar kinds of circumstances). In each case, what I’ve really liked about the results I’ve seen and heard is that along with the judiciously-balanced sound quality the film replicates a single audience member’s view of the concert, rather than the usual “from all-angles” viewpoints, so that one feels like a “bona fide” concertgoer rather than some kind of “voyeur” hovering about the ranks of the players, closely watching them activating their mouthpieces and fingerboards!

Where Otto Nicolai’s exuberant Overture to his opera “The Merry Wives of Windsor” brings together a veritable farrago of characters with engaging personalities and conflicting intentions making for a “spice-of-life” variety of interaction, Sergei Rachmaninov’s darkly-brooding, phantasmagorical tone-poem “Isle of the Dead” presents a bleak scenario of a solitary life’s journey reaching its inevitable conclusion at a forbidding and ultimately pitiless place of interment. No two cheek-by-jowl presentation scenarios could have been more profoundly different!

In some ways, Hector Berlioz’s “Harold in Italy” is even more visionary in its uniqueness – a work for solo viola and orchestra which brings together both compositional ingenuity and idiosyncrasy with little more than quasi-Byronic characterisations by way of portraying the “adventures” of the music’s ostensible hero. In fact the Childe Harold of Byron is largely absent from Berlioz’s depictions of the chief protagonist, the latter being drawn largely from the composer’s own Italian experiences, however much he might have identified with the general traits of the poet’s title character. The work is a collection of scenes through which the traveller passes, bring to each his own, by turns, exuberant, poetic, introspective and downcast set of moods, with Berlioz’s firebrand inspiration setting even the touches of banality in the story alight! -are those indefatigable brigands, for example, perhaps having one round of carousing too many?

Whatever the conjectures regarding any aspect of these presentations, it seemed expectations were simmering when conductor Justus Rozemond stepped up to the rostrum to begin the afternoon’s concert with Nicolai’s “The Merry Wives of Windsor”. And what a beginning! – such a gorgeous opening paragraph to a work! – here were the first notes so magically “sounded” by the violins, the theme fulsomely so by the lower strings, and all repeated by the violins, staunchly but gently supported by the winds and the horns! It brought the first signs of mischief afoot, with a perky theme tossed back and forward between the strings and the winds – a couple of loose notes quickly tucked out of sight! – and then the fun began, with the gossipy exchanges between winds and strings building up a real head of steam – “He wrote what? – Look, it says so here! – the old rogue!” as the two “Merry Wives” read the fat knight Sir John Falstaff’s fawning letters and resolve to plot his downfall! Some smartly brought-off quick-fire exchanges between instruments – “Are you ready? Here he comes! Quick, hide!” and the famous melody sings out, nicely “nudged” at its top note by the strings, and given plenty of sensuous “sway” by conductor Rozemond. The excitement knew no bounds as brass and percussion joined in, anticipating the fat knight’s downfall – and his entry was delicious, the music suddenly acquiring great girth and pomposity from the heavy brass (though I wish they’d kept those heavy accents going through all the unfortunate miscreant’s music!) as the object of the deception fled in shame when he realised his ruse had been thwarted – the music then repeated the sequences almost as before, though reintroducing the “big tune” (one of the world’s charmers, in my opinion) earlier, and with the brasses and percussion helping to celebrate the triumph of goodness and modesty over self-importance and connivance. All in all, It made a splendid opening for the concert.

To grimmer business, then, with Rachmaninov’s “Isle of the Dead”, his sombre evocation of a painting depicting the carrying of a body over water to its resting-place, the music a dark-toned barcarolle whose “wandering” 5/8 time suggests the steady rowing of the oarsman as the boat with its coffin and robed white figure neared a kind of “burial island”. This was an image which the composer first saw in a black-and-white reproduction in Paris in 1907, composing his “tone poem” two years later. Rachmaninov himself conducted the work’s premiere in Moscow in 1909, and subsequently recorded the work with the Philadelphia Orchestra in America in 1930. Incidentally, the artist, Arnold Böcklin, actually made several versions of the work, all slightly differently detailed – and it’s fascinating to learn that Rachmaninov, on subsequently viewing one of the original colour copies of the picture, remarked that he would not have composed the work if he had seen the painting in colour!

I thought the performance by the orchestra a remarkably fine achievement – the opening sounds were steadily and remorselessly brought into play, Rozemond and his musicians conveying a proper “heaviness of spirit” and a sense of lamentation, steadily and patiently maintained. What the winds and strings were doing so well, the brass sturdily continued, helping to build up to the first of the work’s vantage-points, where the music briefly paused, muttered, sighed and exclaimed (lovely work by all concerned, strings, wind and brass, with the latter using their mutes superbly) before resignedly accepting that the journey ought to continue.

And so the lower strings rebegan their steady 5/8 rhythms with even more energy and purpose, building the columns of sound up steadily and impressively, with the brasses sturdily holding the top lines. The winds elaborated on the repeated motifs, the brass moaned, and the strings had a short-lived moment of warmth before the “Dies Irae” melody made a sombre appearance on the cellos, sparking a response through the whole orchestra, the players putting all their energies into the theme, driving it upwards and outwards like an avenging spirit, and propelling the cortege to what seemed like its resting-place on or near the shores of the forbidding island.

The brass sounded the theme (superbly played), weighing down upon us with a kind of finality – but out of sheer desperation came a beseeching strain, a different, more human-sounding plea, led by the strings but coloured by wind and brass, one seeking solace and perhaps salvation from a certain quarter. Such was not to be, as the brass and wind tones rose from out of the orchestral panoply and brutally mocked any such supplications. This brought fabulously full-blooded playing from the strings, and was augmented at the climax by the winds and brass as the harsher realities of death delivered their judgement – one from which it seemed there could be no escape.

Perhaps the most telling sequence in the whole work was the aftermath of this crushing utterance – a steady pizzicato from the strings, repeating the Dies Irae theme, various solo instruments sounding variants of the theme, and the entry of the solo violin playing an agitated tremolando version before ascending to join the winds – oboe and clarinet then linked to the brass, who sounded a kind of “Requiem” (so reminiscent of the last movement of Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetique” Symphony here!) – before the strings again took up the “rowing” 5/8 rhythm, decorated by descending winds, and with the lower strings playing a fuller version of the Dies Irae theme, locking its strains in our memory for all time, and leaving its last few notes floating in the fading ambiences of the scene – amazing!

After such an experience one imagined that the actual concert needed an interval for its audience to be properly revived! Everybody having used the space accordingly, the concert’s second half could proceed…..at this point I need to confess to taking a while as a youthful listener to properly “get” Berlioz’s “Harold in Italy”, the last work on the programme. My first reaction to the work was somewhat akin to Schumann’s famous opinion of Chopin’s “Funeral March” Sonata, whose movements he described as “four of Chopin’s maddest children”. But a beautiful recording by violist Nobuko Imai with Colin Davis drew me afresh into the work’s magical realm – and so it was here with the playing of the soloist, Sophia Acheson, whose gorgeous tones encompassed sounds ranging from a beautifully-wrought self-communing meditation to places requiring full-throated energy and lyricism. However, the great violinist Paganini’s complaint about the work Berlioz had written for him – that there was too little for the soloist to do – certainly bears scrutiny, especially in the light of other concertante works that appeared at around this time, though the composer had never intended to (and never did) write a concerto in a conventional sense!

The work’s sombre opening found the conductor and orchestral players gently coaxing the music out of the void and into some kind of coalescence, introducing a minor-key variant of the melody in the winds that would come to dominate much of the work , with the lower instruments shepherding the lighter ones (the winds and upper strings) into being from their places, patiently and gradually painting a Mediterranean-like ambience into which the character of the wanderer could be introduced. It all came when the music’s key turned to the major, prompting solo viola and harp to speak together, with violist Sophia Acheson responding poetically to her harpist Anne-Gaele Ausseil’s beatific tones, and drawing out further responses from the orchestra, a sunnily-wrought statement of the theme expressed in heartfelt terms. The music took a quixotic turn, with the orchestra sounding fragments of the allegro theme which would dominate the first movement, and the soloist, hesitatingly at first, taking the same music up, and instigating a fascinating interplay between viola and orchestra – the theme was tossed between the participants with glee and gusto, the players handling Berlioz’s capricious demands with skill and perseverance, and bringing real elan to the build-up of excitement and culmination at the movement’s end. Sophia Acheson, Viola

Sophia Acheson, Viola

Of the four movements my out-and-out favourite has always been the second, the “March of the Pilgrims”, music which so impressed Berlioz’s friend Franz Liszt he made a solo piano transcription of this movement alone to perform at his recitals, besides transcribing the whole work for viola and piano! It’s a wondrous soundscape of a kind of processional pilgrimage moving though all kinds of natural and man-made vistas – Berlioz wrote in his memoirs of observing “returning gleaners from fields singing soft litanies to the accompaniment of the sad tinkling of the distant convent bell”, which ties in with the music’s progress here being continually drawn onward by a bell-like sound (in a different key to the music that both the orchestra and the viola are playing – so magical and memorable an effect!). Over this evocative and varied wall of sound the soloist played her first movement melody, and other variants, including a sul ponticello (the bow on the strings close to the bridge) sequence of arpeggiated chords (Berlioz apparently liked to strum his guitar on his mountain walks!), all adding to the overall atmosphere. I would have liked the tempi a notch or two slower and dreamier in this movement, but this pacing brought a kind of “fervour” to the proceedings, which the ending beautifully dissipated as the repeated orchestral notes echoed and re-echoed the bell-like sounds after the pilgrims had disappeared, leaving the viola to make a final arpeggiated comment by way of a farewell.

After this the peasant revelries swung into earshot with the third movement, the winds attractively rustic-sounding at the beginning, with the cor anglais leading the way for the “serenade” section, matched by the oboe’s plaintive tones, as well as the horns, giving golden support. The winds beautifully framed the soloist’s entry, and continued to decorate her figurations with all kinds of felicitous gestures – though the horns missed their footing momentarily, they made amends a few moments later with a similar passage sonorously negotiated. The dance resuming, a particularly beautifully flute solo towards the end of the movement, left the strings to usher the dancers off (the orchestral violas having a brief moment of quiet glory!), leaving the soloist pondering as to whether it was all a dream.

The finale began with a crash! – the music veered between gloom and frantic excitement as the soloist reprised some of the themes from the previous movements. The orchestra “caressed“ some of these fragments in partnership with the viola as if in a dream-like state (a particularly lovely sequence largely with the clarinets), but seemed unable to escape the “allure” of the brigands’ carousings (and driving the soloist from the platform as they did so!), keeping the incisive whiplash rhythms coming splendidly! It seemed everybody was caught in a kind of vortex of brigandish euphoria and largesse! – musically, everybody covered themselves with glory in embracing these bacchanale-like excesses, and especially during the over-the-top repeated passage for strings against snarling brass – fabulous stuff!

Just when the brigands’ excesses had begun to boil over for a third time a deathly hush suddenly overtook the scenario – in the distance could be heard a reminiscence of the Pilgrim’s March (two offstage players) and at the back of the orchestra reappeared the viola soloist, appearing to join in with these sounds, but gradually overcome by the orchestra’s somewhat rogue inclination to rejoin the brigands! Which they did, to brilliant and conclusive effect, the players giving out as if their lives depended on the outcome!

Kudos aplenty to all those people who played a part in both performing and bringing this concert into being – even on film I found it a totally involving and astonishment-provoking experience! The thrill of witnessing a group of musicians literally playing their hearts out in tandem with one another has been a pleasure and, indeed, something of a privilege to witness. Again, congrats to the conductor and the players, to the sterling group of organisers and enablers, and, of course, the supporters, who gave well-deserved acclaim to these performances – by turns, delicious, profound and adventurous!

Donald Maurice (conductor) and Inbal Megiddo (‘cello) rehearse Shostakovich with the Wellington City Orchestra, December 2024, at St.Andrew’s Church, Wellington

Donald Maurice (conductor) and Inbal Megiddo (‘cello) rehearse Shostakovich with the Wellington City Orchestra, December 2024, at St.Andrew’s Church, Wellington