LEONARD BERNSTEIN – Chichester Psalms

CARL ORFF – Carmina Burana

Emma Pearson (soprano), Coco Diaz (counter-tenor), James Harrison (baritone)

Jian Liu, Diedre Irons (pianos)

Auckland Choral (Uwe Grodd, Music Director)

Orpheus Choir of Wellington (Brent Stewart, Music Director)

Wellington Brass Band (David Bremner (Music Director)

Brent Stewart (conductor)

Michael Fowler Centre, Wellington

Saturday, 27th September 2025

Palpable excitement was in the air regarding the Orpheus Choir’s September 2025 concert at Wellington’s Michael Fowler Centre, featuring as it did the ever-popular choral classic by Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, and coupled with a lesser-known but up-and-coming classic from the 1960s, Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms. What gave the concert even more added interest was the double novelty of the Orpheus Choir being joined by a second choir, Auckland Choral, and being accompanied in Carmina Burana by a brass band instead of the usual symphony orchestra. Together these ingredients gave the prospect of attending such a concert the kind of aura and excitement one recalled from festival events in previous years, an atmosphere palpably alive from the evening’s beginning in both the foyer and auditorium.

Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms was composed as the result of a commission from the Dean of Chichester Cathedral, the Rev. Walter Hussey, who over the years successfully commissioned no less than eleven significant works from various well-known composers, failing only in his attempts to procure a work from Igor Stravinsky in 1968! Hussey had actually suggested to Bernstein that a Psalm setting with “more than a hint of “West Side Story” about the music” would be more than welcome; and after some initial misgivings Bernstein became inspired by the Psalm-setting idea, producing in 1965 a work in three movements, to be sung in Hebrew. Its first performance was in New York in July of that year, with the composer conducting, after which came the Chichester Festival’s opening later that month. Bernstein did come to Chichester for the opening but declined to conduct, saying he wanted to hear it “as an audience member”. The success of that occasion was instrumental in inspiring several more commissions by Walter Hussey for future Chichester festivals, from composers William Walton, Lennox Berkeley and the American William Albright.

Here in Wellington the combination of the two choirs galvanised the openings of each of the works programmed in a manner each composer surely intended. The Hebrew words of the Chichester Psalms were translated for us in English surtitles, beginning with the declamatory “Awake, Psaltery and Harp” and with percussion and piano adding to the clamour and excitement of the words. The composer, heedful of his commissioner’s comments referring to “West Side Story” set the following words from Psalm 100 “Make a joyful noise unto the world all ye lands” in a catchy, and in places percussive 7/4 metre, the angularities pointed by the voices and pianists with gusto!

Though I had heard the work only once before, I remembered well the plaintive solo contribution to the second movement with its distinctively “bluesy” flattened note in the melody line – suddenly there it was, in the guise of a memory awakened! From Psalm 23 “The Lord is my Shepherd – I shall not want”, with Coco Diaz’s haunting voice then joined by the choir’s female voices. The choir’s male voices then broke in with sharply-accented cries – “Why do the nations rage?” – similarly sharp, heavy accents rhythms underpinned the women’s voices, until the tenor soloist re-entered singing the words “Surely goodness and mercy”, and with the same affecting “flattened note line” at the words “And I will dwell in the house of the Lord” – so lovely!

At this point something went awry with one of the lower platforms near the players, as if someone had dropped something percussive, making what seemed like an unscheduled entry! – but all continued, with composure only briefly shaken and then restored – the pianists played an extraordinarily anxious and fretful sequence – by turns lamenting, brooding, fretting, and sorrowing – until the men’s voices entered with a gently lullabic Psalm 131 – “Lord, my head is not haughty, nor my eye lofty”, , which the women’s voices joined in semi-canonic fashion, the groups approximating rather than replicating each other’s utterances, until, joining together, the voices sang the same melody wordlessly (all of this was done in a deliciously improvisatory-sounding 10/4 rocking metre).

In conclusion, the voices turned to Psalm 133 – “Behold, how good and how pleasant it for people to dwell together in unity” unaccompanied, except for the concluding “Amen” – sentiments which, in view of the language used by the work would have resonated in a multitude of ways with many present, mindful of the present day-and-age goings on of the outside world.

Plenty of sober reflection then, to take into the interval and then, upon returning, worlds of difference to encounter! – this was Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana”, representative of a long-since departed age’s outrageously expressed declarations of defiance and disdain in the face of the supposed spiritual and social hegemony of the church at that time, here in the form of verses written by the more dissident and dissolute representatives of the era, for our edification, centuries later! Oh, yes, and composer Carl Orff also had a hand (or two) in the latter parts of the process!

Having been familiar with the “traditional” choir and symphony orchestra mix in performances of this work for the last fifty years, I was ineffably curious as to how it would all turn out with the Wellington Brass Band in attendance instead! The opening “O Fortuna” was predictably magnificent, as was the following “Fortune plango vulnera”, both of which had plenty of full orchestra accompaniment in the originals. With the ‘Springtime’ songs the various individual instruments showed what they could do in imitation of normally-heard winds and strings, the first “Veris leta facies” beautifully sung and accompanied. Especially lovely was the second, “slow dance” from Part One, with beautifully “covered” brass notes and gorgeously deep trajectories, seductive in their way. And the beautiful “Chume, Chum, geselle min” featured a gorgeous flute-like solo as well as exquisite singing. Of course the final “Spring movement” Were din werlt alle min” with the “made-to-order” brass fanfares were dispatched by this ensemble and the voices with great pizzazz!

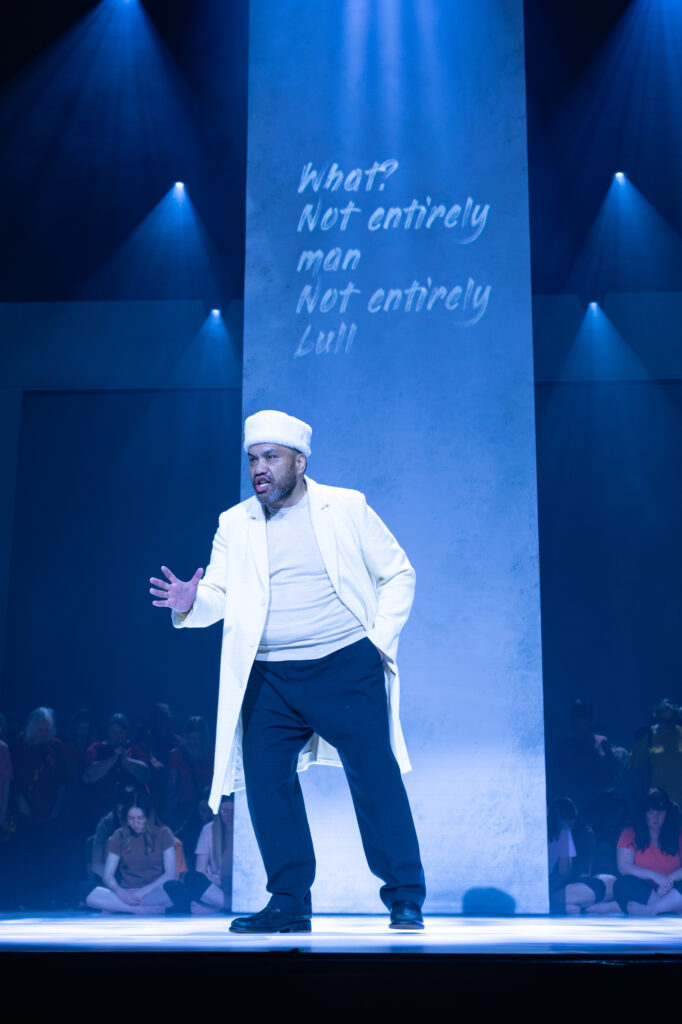

“In Taberna” began with a clarion call and crash, the instruments pushing the dotted rhythms excitingly along in support of the singer, creating a striking contrast with the fantastic “Olim Iacus colueram”, the grotesque “roasted-swan” song for counter-tenor solo – the scene’s eeriness palpably wrought by the singing and playing as the singer was “turned on the spit” and “basted” by serving-wenches!

The band revelled in the other “tavern” scenarios, particularly the percussive interjections during the Abbott’s plaintive lament “Ego sum abbas”, and the exciting running trajectories in the “In Taberna quando sumus” – it was “Oompah!” with a vengeance, in places!

Among the enchantments of this performance were the brass instruments sounding almost like the winds they were replacing, particularly so in “Amor volat undique” (Love flies everywhere) supporting the children’s choir and the soprano, particularly in the latter’s enchanting “Siqua sine socio” – and the accompaniment of the soprano’s beautiful “Stetit puella” (There stood a young girl) – Emma Pearson everything one could wish for vocally, here! – gave us aural ambiences that were almost unworldly in terms of their beauty.

As for the pianists. Diedre Irons and Jian Liu, along with the various other percussionists, they were heroes in terms of rhythmic precision, thematic networking and colouristic variety, picking up on each of the score’s different parts its special character, and adapting according to the season, the time of day, the locale and the different emotions in the music which flash or float by, linger or depart, proclaim or insinuate. Together with the band, and at the varied and persuasive instigations of their conductor Brent Stewart they marvellously realised the patchwork of qualities which make up this ever-fascinating work.

All of the solo singers gave what seemed their utmost to their different roles – James Harrison’s baritone seemed to “fill out” as the work progressed, at his best in the “Ego sum abbas”, (where he enjoyed his touch of play-acting, collapsing on his chair) and at “Dies nox et omnia” (Day, night, and all the World), making a feature of the “falsetto” parts of his recitative and answering in his lower register with real authority. Countertenor Coco Diaz’s “Roasted swan” scene was almost a showstopper in its blend of picturesque timbral ambience and theatricality – a brilliant idea to have him being turned on a kind of “spit” as he lamented his fate! As for Emma Pearson, she enchanted from the moment of her entrance, at “Siqua sine socio” (If a girl lacks a partner”), and came into her own in terms of sheer vocal beauty at “In Trutina mentis dubia” (In the scales of my wavering indecision). The highest notes of the following “Dulcissimi” were effortful compared with the rest, but nevertheless conveyed a kind of “emotion in extremis” pinnacle to which everything had inevitably been brought.

As for the choirs themselves, the Children’s Choir, comprised of singers from Samuel Marsden Collegiate School and Scots College enchanted from its first utterance in “The Courts of Love” sequence, and enjoyed the innocent rumbustifications of “Tempus est iocundum” (Pleasant is the season). The rest was a truly concerted delivery of vocally sonic delight from two recognised bodies of singers performing as one, and galvanising an audience in doing so. Brent Stewart’s direction of all of this was unerringly focused on bringing out in his singers the work’s obvious strengths of articulation, tonal variety and human interest, so that we were satisfied in all aspects of audience experience. As any listener might, I “heard” some things differently at times, most obviously the faster-than-accustomed-to speeds of some of the concerted passages challenging and at times even seeming to blur articulation of words – but such observations merely confirm this performance’s desire to challenge and stimulate those who attended to react and resound what was heard and experienced in the memory. Judging from the reactions of people I spoke with afterwards the occasion was a triumph – and it augurs well for the Orpheus’s return visit to Auckland for a further performance, as guests rather than as hosts. For the moment, in the wake of this initial performance, one raises one’s hands in salute of and acclamation for a mighty and most memorable presentation.

Marc Taddei and Orchestra Wellington – Photo: Andrew Best

Marc Taddei and Orchestra Wellington – Photo: Andrew Best Orchestra Wellington Strings play Shostakovich – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington Strings play Shostakovich – Photo: Andrew Best Orchestra Wellington winds – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington winds – Photo: Andrew Best Orchestra Wellington horns and percussion – Photo: Andrew Best

Orchestra Wellington horns and percussion – Photo: Andrew Best

Ipu Laga’aia as Theseus, Sarah Castle as his Mother, and Joel Amosa as Daedalus with some of the community chorus participants – photo, Emma Brittenden

Ipu Laga’aia as Theseus, Sarah Castle as his Mother, and Joel Amosa as Daedalus with some of the community chorus participants – photo, Emma Brittenden Maaka Pohatu as Minos, King of Crete – photo, Emma Brittenden

Maaka Pohatu as Minos, King of Crete – photo, Emma Brittenden Community chorus participants in “Monster in the Maze” – photo, Emma Brittenden

Community chorus participants in “Monster in the Maze” – photo, Emma Brittenden

Wellington Chamber Music presents:

Wellington Chamber Music presents: