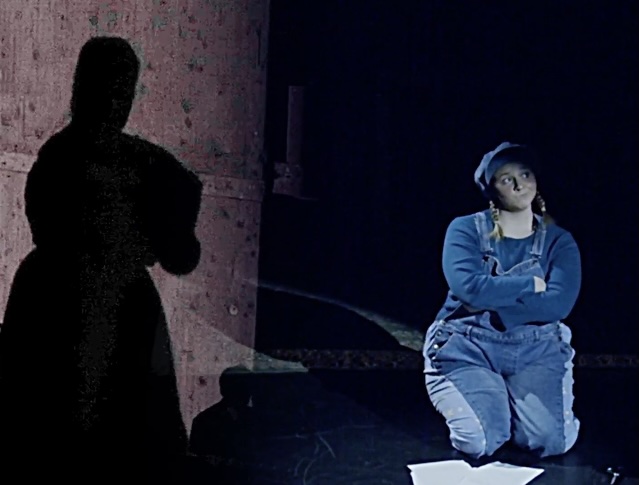

Days Bay Opera Company – BIZET – The Pearl Fishers February 2026 – photo: Simon Hoyle (Southlight)

Days Bay Opera Company – BIZET – The Pearl Fishers February 2026 – photo: Simon Hoyle (Southlight)

OPERA IN A DAYS BAY GARDEN

Georges BIZET – Les Pêcheurs de Perles – Opera in Three Acts

Cast: Zurga – Kieran Rayner (baritone)

Nadir – Zachary McCulloch (tenor)

Léila – Madison Nonoa (soprano)

Nourabad – Joshua Jamieson (bass)

Villagers – Francesca Fagan, Lizzie Summers, Jo Pegler,

Charlotte Secker, Elias Nguyen, William McElwee,

Charle Rainey, Matthew Terry, Joseph Clinton

Director: Rhona Fraser

Conductor: Howard Moody

Rehearsal Pianist: Catherine Norton

Costumes: Ishbel Mclachlan

Refreshments: Seresin Estate Wine

New Zealand School Of Music

Orchestra: Leader – Anne Loeser

Kristina Zelkinska / Ursula Evans / Janet Armstrong (violins)

Victoria Janecke (viola)

Eleanor Carter (‘cello)

Malcolm Struthers (double bass)

Michelle Velvin (harp)

Karen Batten / Jen Vaughan (flutes)

Finn Bodkin (oboe)

Romola Smith (clarinet)

Tor Chiles (bassoon)

Ben Whitton (timpani/percussion)

Canna House, Days Bay, Wellington

12th, 14th, 15th February 2026

Opera in a Day’s Bay Garden is a venture begun in 2010 by Wellington singer, producer and director Rhona Fraser, at her family’s verdantly-appointed native-bush-surrounded residence “Canna House” on the eastern shores of Wellington’s harbour. Its productions have been delighting Wellingtonians and enthusiasts from further afield ever since, even earning the sobriquet of “New Zealand’s Glyndebourne” from a commentator at one point, if on a somewhat more intimate physical scale than that of the world-famous Lewes, East Sussex Festival Opera UK location.

My own first experience of a Days Bay Garden production was in 2012 with Handel’s Alcina, the story’s “magical island” setting fitting the harbourside venue like a glove. Apart from a mere handful of instances since, I’d been prevented by circumstance from attending more recent productions, so it was a particular joy to return for Bizet’s enchanting youthful work Les Pêcheurs de Perles (“The Pearl Fishers”) – one, like Alcina, with a scenario eminently suited to the Days Bay setting’s location.

The opening night performance was in the capable hands of conductor Howard Moody, a Days Bay stalwart from previous occasions, here joining with orchestra leader Anne Loeser in curating every note to telling effect. The players did a splendid job, belying their reduced numbers with on-the-spot accompaniments, and holding their own against even the continuous cicada-accompaniment ambiences from the bush-clad surroundings – I enjoyed many a felicitous instrumental detail, and particularly recall the bassoon’s adroit handling of the melody normally given to the horn introducing Leila’s Act 2 Cavatina “Comme autrefois”.

Each of the three principal singers were Day’s Bay “veterans” who had honed their youthful skills in previous productions, here returning from further offshore studies with the increased confidence and flair born of experience. They were supported by an attractively youthful chorus who brought energy and purpose to their singing, making up for lack of numbers with focused tones and well-disciplined ensemble (particularly impressive in moments when the groups’ antiphonal exchanges from different parts of the garden unerringly “found one another” to mellifluous effect!

Together these forces brought out a performance which I thought most satisfying, with each soloist “sounding” their character’s dramatic and musical raison d’etre – baritone Kieran Rayner was a consistently sonorous Zurga, splendidly conveying the character’s plethora of conflicting emotions regarding his friendship/rivalry with his old friend Nadir (here drawn with beautifully focused tones throughout by tenor, Zachary McCulloch). Of course, everybody awaits in breathless anticipation the opera’s great Act One tenor/ baritone duet Au fond di temple saint, and in which both singers here were, I thought, ideally-matched in individual timbres and and intensities. Elsewhere (apart from a slight lessening of tone at the very top of his range) Rayner vividly conveyed Zurga’s contrasting comradeship and anguished jealousy regarding his friend Nadir’s reawakened passion for Léila, the beautiful Priestess. For his part (and to my very great pleasure) McCulloch’s delivery of the Romance “Je croix entendre encore” was so very beautifully and sensitively phrased – comparing favourably with the many versions I heard on recordings and on various on-line videos – what a treacherous piece for tenors it can be!). A small point was that I wanted him to take his hands out of his pockets a bit more often when singing!

Madison Nonoa was Léila, the mysterious virgin Priestess whose reappearance in the opera reflames old passions between Zurga and Nadir. She looked and sounded the part admirably, though a somewhat recalcitrant face-concealing veil seemed to give her more trouble than security at times – I also felt her very first entry would have been helped by some kind of marked-out or unlifted focal-point she could have made her own and which would have helped create the necessary “Priestess” aura. Her enchanting singing’s softer strains could in places hardly be registered in those vast out-of-door spaces, though her voice for the most part sounded wonderfully at ease with the role’s stratospheric vocal quality – and she was a suitable match for bass Joshua Jamieson’s capable and sonorous Nourabad (in the small but effective part of the High Priest assigned to supervise her activities as “guardian spirit” for the boats of the pearl fishermen). But the need for a kind of “shrine” for her was accentuated when Nadir crept into her presence and sat beside her, the pair then obscured by rows of flags along the stage-front, and whose decorative effect became more distracting than festive.

Despite the production offering no surtitles, whose presence would have finetuned some of the story’s detailing, the drama’s overall impact was readily conveyed by the singing and playing, the venue allowing its audience a proximity to the sound and action of it all, a kind of involvement which intuitively engaged one’s emotions – even Nonoa’s recalcitrant veil couldn’t distract from her character’s allure and fascination.

The production with its clean-cut, orange-and-white, almost religious cult garb for the indigenous islanders had a curious “updated” aura about it, most noticeable when the villagers were enjoined by Nourabad to construct a “burning at the stake” kind of pyre to which they added lashings of what looked like petrol, before tying up the traitorous Nadir and the impious Léila to the structure, intending to put a grisly end to them both.

We were fortunate with the weather, blessed by clear, settled skies on the opening night – besides the enchanting “cicada chorus” that accompanied the singers the only other natural distraction I noticed was a briefly annoying airborne “bug” which occasioned an involuntary “swat” from the tenor during the famous duet, which, if anything, intensified the ambience of the performance’s energies!. As the forecast for the oncoming weekend gradually deteriorated director Rhona Fraser cannily brought forward the timing of the final day’s performance by way of thwarting the projected onset of rain, which strategy seemed to work, and the show went on. Though not exactly a replication of Thursday evening’s al fresco splendours the worst was adroitly avoided and honour was satisfied – full marks to Rhona Fraser AND Days Bay Opera!

Julien Van Mellearts (Renato) and Jared Holt (King Gustavo)

Julien Van Mellearts (Renato) and Jared Holt (King Gustavo) Natasha Te Rupe Wilson (Oscar) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Natasha Te Rupe Wilson (Oscar) – photo, Stephen A’Court Madeleine Pierard (Amelia) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Madeleine Pierard (Amelia) – photo, Stephen A’Court

Emma Pearson as Musetta

Emma Pearson as Musetta

Act One: Wade Kernot (Coach), Manase Latu (Count Ory), Moses MacKay (Raimbaud), NZ Opera Chorus – photo credit: Lewis Ferris

Act One: Wade Kernot (Coach), Manase Latu (Count Ory), Moses MacKay (Raimbaud), NZ Opera Chorus – photo credit: Lewis Ferris Le Comte Ory – Act Two (beginning) – NZ Opera Chorus, with Emma Pearson (Countess Adele), Tayla Alexander (Alice) and Andrea Creighton (Ragonde)

Le Comte Ory – Act Two (beginning) – NZ Opera Chorus, with Emma Pearson (Countess Adele), Tayla Alexander (Alice) and Andrea Creighton (Ragonde)